Faced with challenges moving recycled materials in recent years, MRFs and curbside recycling programs have occasionally opted to stop accepting certain materials, particularly experimental or harder-to-market packaging types.

But technological advances may be rewriting that playbook so that MRFs may not need to choose between accepting new packaging and emphasizing the quality of existing material streams, according to panelists at the 2024 Resource Recycling Conference in Louisville, Kentucky, last month.

In “Saying Yes in the Land of No,” speakers discussed how MRFs can add materials into the mix of what they accept from local programs.

Once common during the rollout of single-stream recycling in the 2000s, the move to expand material lists saw a snag in late 2017, when MRFs around the country faced challenges moving materials because of China’s pullback from the recycled commodities market.

Market strife led some local recycling programs to stop accepting certain materials because of a lack of markets or increased costs. Communities often focused on core commodities like fiber, PET and HDPE containers, aluminum cans and glass. Some communities tried to return to dual-stream recycling; others promoted drop-off options.

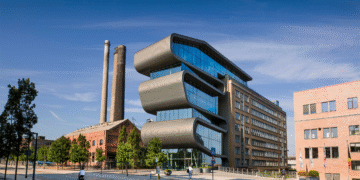

But advances in sorting technology are opening up new possibilities. Nowhere is that more evident than at Rumpke’s MRF in Columbus, Ohio, which opened in 2024 and features a whopping 19 optical sorters.

Not only is the technology minimizing residuals – the company has reported finding virtually no plastic in its residue line – but it’s also enabling curbside collection of additional materials. In September, Rumpke announced it would begin accepting clamshells from curbside recycling programs.

“We’ve added multiple items to our acceptables list, and it’s a very clear, for us, two-part story,” said Becky Reichenbach, Rumpke corporate recycling marketing manager.

The equation that ends with ‘yes’

Those two parts are determining whether the material can be sorted safely and efficiently, then whether there are long-term and responsible end markets.

“They can’t be someone who’s maybe going to build a site, and maybe it’ll be ready in five years,” Reichenbach said. “It has to be someone who is consuming that commodity now.”

But getting those two parts of the equation takes a lot of work by different stakeholders. In a project that brought paper cups into Rumpke’s MRF, for instance, the Foodservice Packaging Institute went to paper mills and asked them to pledge to accept mixed paper bales that included paper cups.

“When the leadership team at Rumpke got this pledge, it was probably no more than 30 or 60 days later that we added paper cups to our acceptables list,” Reichenbach said, “because it covered every mill we ship to and then some.”

Additionally, sortability in a MRF can depend greatly on the packaging design employed by the producer.

Melissa Walden, Colgate-Palmolive’s North America packaging sustainability innovation senior manager, described the company’s effort to make all of its tube packaging recyclable. That has involved large-scale redesigns for some packaging, like Colgate’s toothpaste tubes.

In the lower tube portion of the package, “we took what was a multi-layer structure, definitely not recyclable with the foil, and we moved it to an HDPE laminate,” Walden said. Further up in the “shoulder” of the tube, Colgate worked on technical improvements, like swapping out the high melt-flow resin for a low melt-flow option. That aids in mechanical recycling of those products by reclaimers.

Colgate is also working with MRFs to get a real-world look at how its products are sorted. The company is collaborating with Mazza Recycling, which accepts Colgate tubes. One way the companies are studying the tubes is by using equipment from robotics firm Glacier to count how many tubes are coming through and getting sorted.

“It’s been helpful to get that input from the MRF level,” Walden said.

MRF skepticism should be expected

Working directly with MRFs also helps to mitigate another potential challenge: Walden noted there is sometimes skepticism among MRF operators when considering new materials.

Amy Uong knows about that dynamic. Now the senior recycling manager at coffee pod producer Nespresso USA, Uong previously worked in the MRF world for Sims Municipal Recycling, which is now Balcones.

“There are a lot of ‘nos’ out there, and working in the MRF operating world, I was one of the folks that said no,” Uong said during the panel.

As a manufacturer of typically non-curbside-recyclable products, Nespresso has long provided a mail-in recycling option for its aluminum coffee capsules. But it hasn’t moved the company far enough towards its goal of 60% diversion by 2030. Nespresso leaders knew the company needed to expand beyond mail-back. So, in 2018, Nespresso approached Sims, the processor handling recyclables collected in New York City’s curbside program.

Back when the Nespresso-Sims discussion first began, Uong, then at Sims, was skeptical. But company leaders decided to try it out, agreeing to accept and sort coffee pods collected curbside in New York City.

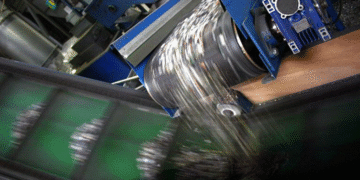

The agreement led to Nespresso investing $1.2 million to install a shredding system and an eddy current separator at a Sims glass processing facility in New York. Those equipment additions were aimed at helping Sims prepare the capsules for more value recovery.

Uong echoed the value of packaging firms working directly with MRFs, helping all parties understand how a given product flows through the sorting system. For Nespresso, the pods’ size and shape meant they fell through the glass screens and ended up with the MRF glass. With that understanding, Sims could target its equipment installations to the glass cleanup phase of the sorting process.

Earlier this year, Nespresso reported 350 tons of coffee pods have been recovered through this curbside option to date. And this year, Nespresso and Balcones announced the curbside recycling availability was expanding to cover certain low-rise residential buildings in Jersey City, New Jersey.