Over just a few years, robotic sorting has gone from a gee-whiz laboratory curiosity to a key technology in a number of different types of facilities.

Over just a few years, robotic sorting has gone from a gee-whiz laboratory curiosity to a key technology in a number of different types of facilities.

After compiling data from major robot providers, Resource Recycling estimates over 80 robots are either working or have been purchased in the U.S. and Canada. They’re sorting residential and commercial recyclables, mixed-waste, plastics, shredded electronics, and construction and demolition debris.

The first known sorting robot to work in a U.S. recycling facility was installed only three years ago. That’s when fledgling company AMP Robotics installed and tested its robot at Alpine Waste & Recycling’s Altogether MRF near Denver. Since then, the recycling sector has embraced robotics.

“We’ve been really fortunate to see a lot of industry demand come out of it,” said Matanya Horowitz, founder of Denver-based AMP Robotics. “We always thought the robots would be a big deal for recycling, but the quick uptake of the systems has been … a rewarding surprise for me personally.”

And the trend continues to build. On May 2, Bulk Handling Systems (BHS) sold two of its MAX-AI AQC-4 units, each with four sorting arms. Plessisville, Quebec-based recycling equipment provider Machinex announced last week that its SamurAI technology has been deployed in partnership with AMP at a Quebec MRF.

Resource Recycling took a look at what problems the emerging technology is solving for customers, where robots are being installed, how much they cost, what roles they’re filling and how they’re continually developing.

The market, by the numbers

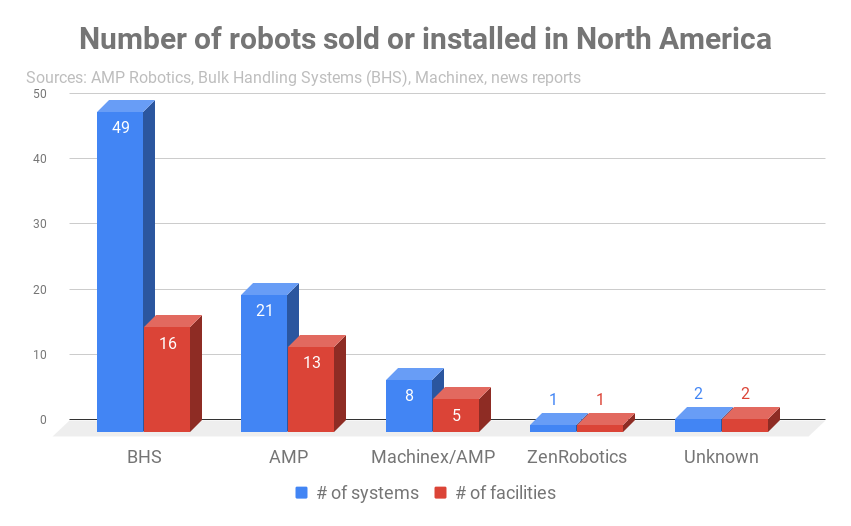

Resource Recycling compiled data from major players in the North American robots business – AMP Robotics, BHS and Machinex – and supplemented the data with information obtained from news sources and past reports.

Here are a few takeaways:

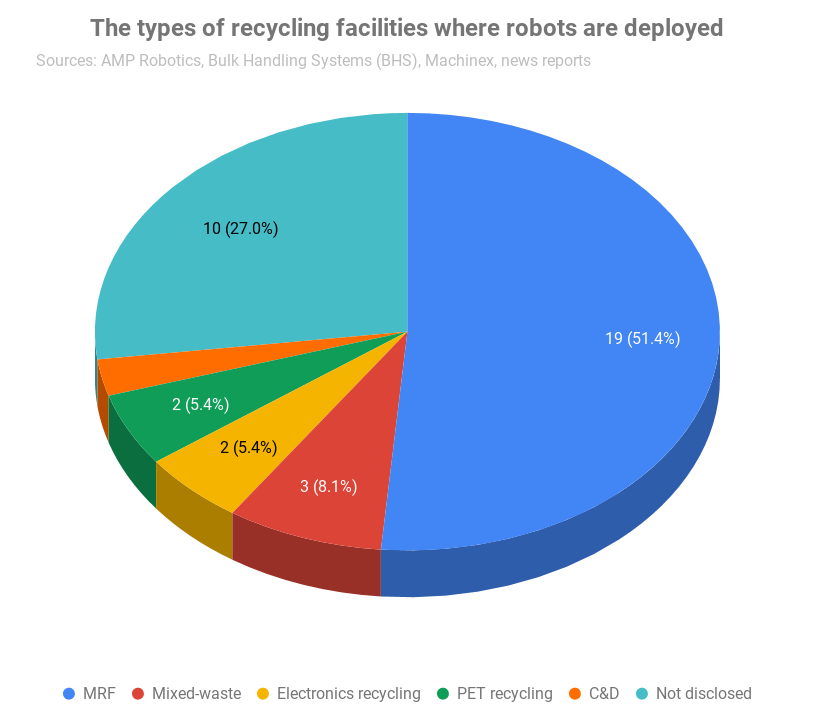

Mostly sorting curbside recyclables: For the most part, robots are working in single-stream MRFs. The 37 identified facilities in the U.S. and Canada with robots break down this way:

BHS has the most systems deployed: The numbers deployed and sold by each company are somewhat difficult to pinpoint because installations and contract signings are ongoing, and some customers don’t want to be disclosed. Nevertheless, Resource Recycling provided a conservative estimate of the number of systems that have been sold or deployed in U.S. and Canadian facilities (the numbers below count visioning systems, including those deployed on a standalone basis or integrated with sorting equipment; they do not strictly count the number of robotic arms):

BHS has the most systems deployed: The numbers deployed and sold by each company are somewhat difficult to pinpoint because installations and contract signings are ongoing, and some customers don’t want to be disclosed. Nevertheless, Resource Recycling provided a conservative estimate of the number of systems that have been sold or deployed in U.S. and Canadian facilities (the numbers below count visioning systems, including those deployed on a standalone basis or integrated with sorting equipment; they do not strictly count the number of robotic arms):

They’re all over the continent, but they especially like sunny weather: Looking at geography, the robots have been installed in 15 states and three provinces. One-third are in California, which is perhaps not surprising given the state’s sheer size, as well as policies encouraging materials diversion:

They’re all over the continent, but they especially like sunny weather: Looking at geography, the robots have been installed in 15 states and three provinces. One-third are in California, which is perhaps not surprising given the state’s sheer size, as well as policies encouraging materials diversion:

- British Columbia: 1 unit (AMP Robotics)

- California: 27 units (25 from BHS, 2 from AMP)

- Colorado: 1 (AMP)

- Delaware: 1 (BHS)

- Florida: 6+ (all AMP)

- Illinois: 2 (1 Machinex/AMP partnership, 1 unknown)

- Indiana: 2 (both AMP)

- Michigan: 2+ (all AMP)

- Minnesota: 3+ (all AMP)

- Nebraska: 1 (AMP)

- Ontario: 6 (all Machinex/AMP)

- Oregon: 2 (both BHS)

- Pennsylvania: 8 (all BHS)

- Quebec: 1 (Machinex/AMP)

- South Carolina: 9 (all BHS)

- Texas: 3 (1 BHS, 1 ZenRobotics, 1 unknown)

- Virginia: 2+ (all AMP)

- Wisconsin: 4 (3 BHS, 1 AMP)

Customer adoption

The units have quickly spread throughout the marketplace. A map produced by Resource Recycling in early 2018 showed fewer than a dozen across the country.

The adoption by the recycling industry has come for a number of reasons: persistent staffing challenges, and difficult markets requiring lower processing costs and better bale quality. Also, robots aren’t prohibitively expensive, compared with some other advanced sorting equipment.

Resource Recycling in August 2018 wrote about the first MRF to install a SamurAI: Lakeshore Recycling Systems’ Heartland Recycling Center near Chicago. At the time, CEO Alan Handley noted difficult fiber markets prompted the move, but he also emphasized the benefits of reducing human sorters.

Chris Hawn, CEO of Machinex Technologies (a division of Quebec-based Machinex Industries), noted the obvious problem solved by robots is labor, but he said they also bring other benefits in the areas of safety, sorting reliability and, ultimately, optimization.

Horowitz of AMP hears from customers that production costs and labor issues are the biggest challenges the AMP Cortex units address, he said. China’s restrictions on recyclables imports had ripple effects lowering commodities prices, he said, and a lot of people recognize robots and automation as a way to address that.

A grant application to help purchase two BHS robots for a Clackamas, Ore. MRF provides insight into the benefits and costs of the systems. Pioneer Recycling Services received a grant from Portland, Ore.-area regional government Metro to install two robots on the container line. Pioneer plans to reduce four manual sorting positions by attrition.

“If successful, the robots will make more picks of their target and prioritized commodities than a human sorter can accomplish,” according to the 2018 grant application.

The document also provided insight into robot costs, information that AMP, BHS and Machinex declined to release publicly. The BHS MAX-AI AQC-1 units each cost $200,000. That does not include installation, freight, electrical and other costs, which, in Pioneer’s case, totalled about $169,000.

The robots are evolving

As fast as the robots are being sold and installed, the technology and its applications are also quickly changing.

Some MRFs are now using visioning systems independent of mechanical sorting arms. Horowitz explained the visioning system can help facilities conduct waste characterization studies for less cost than bringing in an audit crew to break bales, separate items and weigh materials. They also provide key operations feedback, he noted.

Rich Reardon, vice president of sales and marketing for Eugene, Ore.-based BHS, said his company has customers using VIS, short for visual identification system, to meet their contractual audit obligations by providing an ongoing assessment of the material stream.

As far as sorting is concerned, BHS has also added more recognition and sorting capabilities under each steel structure. Last week, BHS sold two MAX-AI AQC-4 units – each of which has four visioning systems and four sorting arms – to an unnamed PET reclaimer in Southern California. Meanwhile, Machinex recently installed a unit with one visioning system and two sorting arms at the Sani-Éco MRF in Granby, Quebec.

BHS has also integrated its VIS with optical sorters, improving their material recognition capabilities. And last week the company unveiled the AQC-C, which contains a VIS connected to one or more CoBots, which are designed to work alongside human sorters.

The systems are also moving outside the municipal recycling sphere. Over the last several months, AMP has installed sorting robots at two electronics recycling facilities owned by ERI, a nationwide IT asset disposition and e-scrap recycling company. ZenRobotics began in the C&D sorting space but is now also offering a system for sorting curbside materials. AMP and Japanese company Ryohshin co-developed a C&D system, which AMP plans to market in North America.

Other applications could see robots in the future. AMP is exploring organics and automotive scrap sorting. Both Hawn of Machinex and Reardon of BHS said they see opportunities in e-scrap, C&D debris and elsewhere.

A longer version of this piece will appear in the July 2019 print edition of Resource Recycling magazine. Sign up for the magazine today.

Photo courtesy of AMP Robotics.

More stories about markets

- ‘Operational readiness is high’ as Oregon rolls out EPR

- Pizza box demand declining, report says

- Paper operations close in Georgia, Texas