On July 1, Malaysia implemented new regulations that include an apparent ban on U.S.-sourced imports of scrap plastic, causing confusion and consternation both domestically and in Southeast Asia. And although commodity brokers indicated that the changes were disrupting supply chains ahead of implementation, they added that relief could be seen soon.

In May, Malaysia’s Federal Government Gazette published notice of new customs rules requiring all imports of scrap plastic under the 3915 tariff code to be approved by a government-owned certification organization called SIRIM Berhad, to comply with the Basel Convention. In addition, SIRIM will approve imports only from countries that are party to the Basel Convention, the global treaty regulating waste shipments, or that have a separate agreement between the two countries. The U.S. does not meet either of those conditions.

In late June, James Derrico, vice president of new business at brokerage CellMark, told Plastics Recycling Update, “Originally we had seen a large pull back on buying into the Malaysian market.” He added that prices had softened but customers were still buying. “It’s very hard to tell if this will actually end up affecting scrap from the U.S. market.”

Another seller agreed, saying, “There is ongoing discussion, and as of right now they’re saying no (to U.S. scrap imports), but they’re still going back and forth, and it’s very much up in the air.”

Both private and government stakeholders in Malaysia “are well aware that they have to figure out how to incorporate the U.S. into this policy,” said the second seller, who requested anonymity to discuss sensitive talks. “I don’t expect to see an outright ban, and there may be some hiccups along the way,” the source said, adding that market players expect to hear news this week – if only to delay the regulation to allow more clarity – with “full resolution” expected by September.

As with tariffs, it’s unclear how the new regulations are being implemented. Although the effective date is July 1, it may not be enforced until September, the seller said, perhaps affecting only shipments made after that date. “I think it’s not even clear for them,” the seller said, referring to the government stakeholders.

The seller added that Malaysia’s plastics manufacturers had been in talks with the government, and while “sometimes in the past the government’s been very, very adversarial about it,” the regulations were originally intended to prevent imports of specific materials like e-plastics rather than to entirely cut off recycled plastics.

Ahead of the implementation, Steve Wong, CEO of plastics brokerage Fukutomi, wrote in a June 30 commentary that most Asian recycling operations had suspended raw material purchases and cut production. He added that they are facing overflowing warehouses, amid “extremely weak” demand for recycled plastics, including PE, PP, PET, and engineering grades such as acrylonitrile-butadiene-styrene (ABS), high-impact polystyrene (HIPS) and nylon (polyamide).

“With downstream orders lagging, raw material prices falling, global political instability, and the impact of U.S. trade policy, the price gap between virgin and recycled plastics — particularly PE and PP — has narrowed significantly or even reversed, severely undermining the competitiveness of recycled materials,” Wong wrote.

Earlier in June, Wong wrote that “the scrap plastics market in Malaysia has come to a virtual standstill,” particularly for LDPE film, PET bottle and rigid polyolefins. The most recent U.S. trade data shows that January-April plastic scrap exports were lower by 12% on the year, at 128,195 metric tons. Malaysia’s share of the total dropped to 5%, from 10% a year ago.

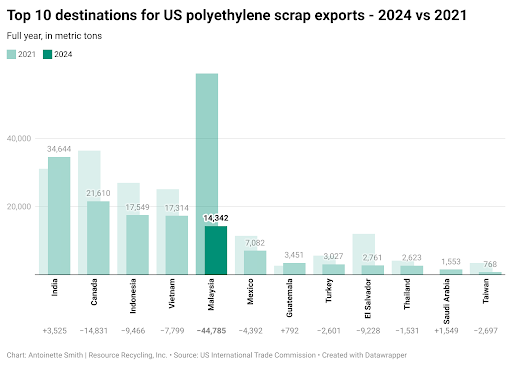

For PE scrap exports specifically, in 2021, Malaysia was far and away the most popular destination, according to data from the U.S. International Trade Commission. By 2024, PE scrap shipments to the country had dropped by 75%, but the country still was in fifth place. Although most countries saw diminished volumes over that time period, Malaysia’s drop was the most pronounced. For an interactive version of the graph below, click here.

In an interview with Plastics Recycling Update, Wong attributed the downward trend in U.S. scrap exports to several factors, including public and governmental misperception of recycled plastics as waste or trash rather than as valuable commodities, along with restrictions both from localities and from shipping providers, increasing fees to export materials and increasing domestic demand.

Basel watchdog supports stricter guidelines

The changes come more than four years after the Basel Convention was amended to regulate scrap plastic shipments, which in particular threw a wrench in the U.S. e-scrap industry practice of exporting the engineered plastic fractions of end-of-life electronics, usually to southeast Asia. Each country that is party to the Convention must enact the Basel rules by adopting compliant domestic regulations.

The Basel Action Network (BAN), a U.S. exports watchdog group, applauded the Malaysian government for the new import regulations.

“We are ecstatic that this new law aims to stop much of the harmful plastic waste moving in containers each day from Los Angeles to Port Klang under the guise of recycling,” Jim Puckett, founder and chief of strategic direction for BAN, said in a release. Puckett described the concept of exporting plastic for recycling as “a complete sham,” and said it is “a relief that the U.S. contribution to this plastic waste shell game is increasingly outlawed.”

Especially in Southeast Asia, Wong wrote in June, countries with recycling infrastructure are increasingly unable to import post-industrial and post-consumer plastics from Europe and the U.S. due to legal constraints, resulting in an increase in recyclable plastics going to landfills or being incinerated. “This trend runs directly counter to global goals of reduction, reuse, and recycling,” Wong wrote.

Ted Kaiser, president of Dock 7 Materials Group, told Plastics Recycling Update, “The reality is that recycling is real. No one is paying us money to throw out plastic.” And while Kaiser acknowledged that abuse can and does occur, as it does in any business, the majority of exported plastic scrap is recycled.

“And the reality is that if we are cut off from the big port option, whether it’s Malaysia or anywhere, we (the U.S.) would be choking on plastic. There’s just not enough domestic capacity to recycle all these materials, and there’s plenty of materials that they take overseas that no one here in the States takes at all,” he said. One example is LDPE film bales of B-grade and lower that are used to make bags, plastic lumber and other items, in lieu of virgin plastic.

“I would love to sell it here, and it would probably be a lot easier, but the reality is, it’s not, and if it wasn’t (exported), we would be landfilling that plastic, or burning that plastic,” he said. “So I know, yes, it’s not ideal to be putting plastic halfway around the world, but, you know, it is a real option.”