Seeing the lack of smaller-scale systems suited for processing small personal devices containing lithium-ion batteries, Houston-based Gloyd Recycling Solutions developed what it says is the first marketed device to shred battery-containing devices of laptop size and smaller.

“The big battery recyclers only want 30,000 or 40,000 pounds. So what are the small recyclers to do?” company founder Jeff Gloyd told E-Scrap News. “They put them in five-gallon pails, hoping that they don’t have reactions, and they store it next to 35,000 pounds of other reactive batteries. And that’s why we have facilities burning down.”

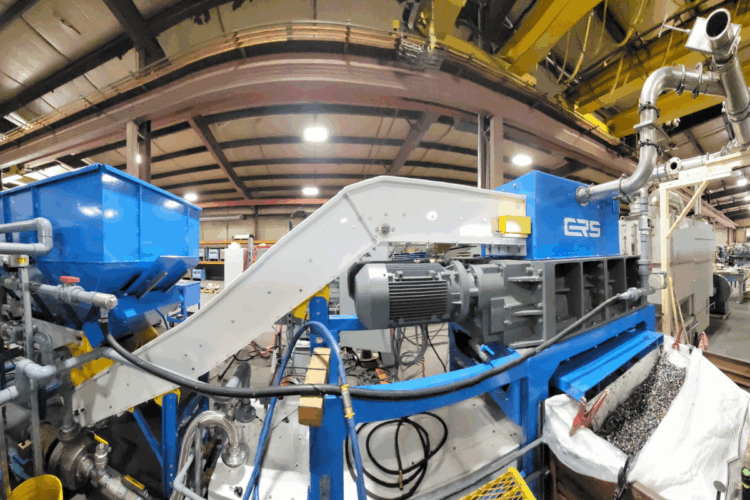

The Battery-In-Device Shredding machine, or BIDS, handles smaller devices — such as electric toothbrushes, remote controls and children’s toys — and is well-suited for smaller recyclers, Gloyd said. The system uses a feed hopper to load a screened wet shredder. Devices then are mechanically separated into plastics, metals and black mass, the battery material obtained during recycling that contains valuable metals. A wet scrubber eliminates emissions.

The machine has a small footprint, sized to fit inside a 40-foot shipping container. Its modular design enables simple setup, requiring only electricity and customer-added water for the two systems to deactivate the batteries and to separate plastics from metals. As for water loss, the machine doesn’t require discharge permits, since the system retains most of the fluid.

Gloyd said the capacity is about a ton per hour of battery containing devices, though the density of the material affects the throughput rate. He pointed out that while the capacity may be dwarfed by shredders for printers, copiers and other bulky items, “if you think about 2,000 pounds of earbuds, that’s a lot of earbuds.”

Focused on reducing risk, maximizing throughput

Processors globally have been employing wet shredding for some time, Gloyd said, but mostly on larger batteries, such as EV packs, due to the processing volumes required to recoup a company’s capital investment in the equipment. “We’re taking that same concept and just doing it on a much smaller scale.”

By flooding the shredding chamber with water, and starving it of oxygen, the battery is unable to expand and cause a thermal event. “We don’t want them reacting in supersacks or in gaylords after they leave the system” and causing a fire or injury, he said.

Larger-scale processors are typically focused on a clean recovery stream from black mass, requiring removal of alkaline batteries from devices to avoid contamination, Gloyd said.

BIDS processes most battery types, which still results in a potential revenue stream – albeit slightly lower in value – but the BIDS focus is on reducing risk from batteries and lowering the upfront costs associated with manually removing unsuitable battery types, Gloyd said. “We can do it much more efficiently, which then we think can lower the prices (of the process), which gets more material into the recycling stream.”

Using earbuds as an example, manual separation would result in perhaps 10 pounds of material processed each day by each employee, Gloyd said. “There’s not enough you could charge to a supplier to ever make money.”

First unit sold, future plans in the works

Over the course of about two years, Gloyd’s company designed the unit and sold the concept, and now the first unit is operational, he said. It’s currently being decommissioned for shipping to the customer who bought it.

In a situation familiar to any manufacturer today, Gloyd is monitoring global trade developments, though almost all BIDS components are made in the U.S. For the one piece that is imported, if tariffs present an untenable scenario, “we might have to look at sourcing that piece more domestically, which we could — that’s not an issue. So I think we’ve got a good plan so that our clients and ourselves aren’t affected by any of the geopolitics. As far as logistics and shipping, no issue.”

Looking ahead, Gloyd said the company may develop an add-on to accommodate larger items, as a response to customer feedback. And while the current BIDS design produces a mixed fraction of ferrous and nonferrous metals, some potential clients are unable to further process the mixture to optimize the value of the recovered materials.

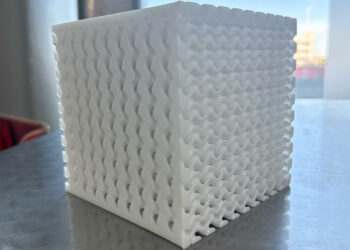

Gloyd is exploring if the valuable metals in the black mass could be concentrated using some kind of technology, he said, such as an optical sorter or an eddy current, to get cleaner and thus more marketable aluminum and other commodities.

For ITAD firms that receive battery-containing devices, that could allow them to recover additional commodities rather than handing them off to another service provider, Gloyd said. “ITAD operators typically don’t have any (eddy) currents, or any kind of centrifuge to concentrate black mass, so we’re looking at engineering what we’re going to call a metal concentration unit, which would be similarly sized” and could sit adjacent to the BIDS.

As for the very first unit, “we stopped using the word ‘prototype,’ even though it is the first, and it’s easier for people to say it’s a prototype,” Gloyd said. “But essentially it’s the first operating unit of its kind, and it is operating, which I think is very exciting.”