More than three months after China announced it will restrict recyclables imports, key details on logistics and timing of the new regulations remain unknown. But industry associations are piecing together some more concrete facts about the downstream and upstream ramifications of the actions.

Three leaders recently offered their thoughts and perspectives on the Chinese restrictions and what they mean for the future of the business.

Adina Renee Adler, senior director for government relations and international affairs at the Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries (ISRI), shared information she’s gathered from visiting China and speaking with industry insiders and governmental authorities. She laid out what is known and unknown about future shipments to the world’s largest importer of scrap materials.

In a webinar, Anne Germain of the National Waste & Recycling Association (NWRA) expanded on the details of a practically unachievable contamination limit that’s been proposed for imports into China.

And in an interview, David Biderman of the Solid Waste Association of North America (SWANA) said communities don’t want to undo decades of outreach work and tell residents to stop putting certain items in the bin, even if China’s scrap policies are shaking up market realities.

Permits and contamination

U.S. exporters have seen their buyers diminish or disappear as Chinese authorities delay issuing new import permits for the fifth month in a row. Adler said there may be a few permits issued in November, but that is mostly information gleaned through rumors from industry players.

“We have heard that they will issue import licenses in 2018, but we’re pretty sure it’s going to be a lot fewer licenses and that whatever licenses are issued are going to have significantly less quotas involved with them,” Adler said. However, she added, no import licenses will be issued for materials covered by the ban.

During a recent conference call with investors discussing financial results, an executive at Waste Management said China has granted a few import licenses. Accordingly, Waste Management is preparing to send shipments to Chinese buyers during the fourth quarter.

Chinese officials have proposed a 0.3 percent maximum contamination level on scrap imports. Adler said there is talk that the 0.3 percent limit will go through, but also that she’s heard the government is considering a somewhat more lenient 1 percent threshold.

It’s well accepted the 0.3 percent contamination level would be virtually impossible for the U.S. recycling industry to meet. But in an Oct. 26 webinar hosted by the U.S. EPA, Anne Germain of the National Waste & Recycling Association noted there are the official Chinese standards, ISRI standards and Chinese buyers’ standards. In recent years, shipments have largely adhered to the buyer’s guidelines rather than the official Chinese government standards, Germain said.

“The previous standards were not strictly enforced, so the real question is how strictly, even if these are adopted, would they be enforced,” Germain said.

Importing agents who still have permits have been able to dictate quality, Germain said, “and they can be a lot pickier than they have in the past.”

Adler said it’s unclear how Chinese officials came up with the 0.3 percent contamination limit or what the thinking was behind that figure, whether Chinese regulators see it as a realistic level or whether it’s meant to be a de facto ban. It’s also unknown when the restriction could go into effect, because the country hasn’t announced an implementation date.

Market alternatives

Adler said she thinks there are other market opportunities around the world. ISRI has heard of a number of Chinese companies moving operations or opening up new operations in Southeast Asia to get around this policy.

ISRI staff members were in India for the Bureau of International Recycling bi-annual convention in mid-October. Adler said India is an important market currently but also presents a large opportunity. The country is working to bolster its own domestic materials recovery, but it is still predicted to be a major downstream market for U.S. and other countries’ exports.

“That opportunity definitely is going to be there for the foreseeable future,” she said. She added ISRI wants to make sure India doesn’t feel like that growth means the country is replacing China as the importer of the world’s garbage.

“We certainly don’t want them to go down the path of a similar policy,” she said.

She also described growth in already strong end markets including Canada, Mexico, Turkey and other countries.

Adler said she does know of companies that are still successfully exporting plastics, paper and metal to China, at least until those importers run out of permits. She offered some thoughts on why customs agents have allowed those shipments.

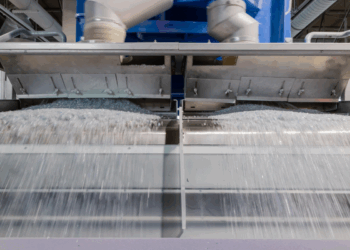

“It’s really about what they perceive as quality,” she said, noting companies could benefit from technology upgrades, outreach to households or other measures.

Municipal outlook

Biderman, whose organization represents mostly public sector solid waste professionals in the U.S. and Canada, expanded on the trepidation recycling programs feel about halting collection of certain materials.

“Local governments have spent a lot of time, a lot of money educating their residents on how to recycle and what should be recycled, set up systems and infrastructure to capture that material,” said Biderman, executive director of SWANA. “It would be bad for recycling in general to have to retreat from those systems, and history suggests that it can be very difficult. If you turn recycling off, even for one type of material, it takes years to be able to turn it back on to the version (or) level it once was.”

He referenced a sentiment shared during a recent webinar hosted by The Recycling Partnership, noting that “if anybody says they know what’s going on in China, they don’t.”

But he and other industry insiders point to some potential outcomes if China continues to restrict imports as the country increasingly has in the past couple years. First and foremost, the U.S. and other countries will be forced to lessen their dependence on China as a downstream outlet for recyclables.

“Diversifying one’s customer base is always a smart thing,” he said, noting brokers are already looking to other markets, particularly Southeast Asia.

Second, in the longer term, Biderman said declining exports to China could mean a bolstered U.S. processing industry. But he estimates the industry needs at least three to five years to bolster its domestic processing industry to the point where material diverted from China could find a home in the U.S.

“It takes a long time to purchase property, get a permit, start construction and then start operations,” he said. “It’s not a turnkey kind of thing. It’s challenging to build a lot of these facilities.”

He advised local governments to evaluate their contractual relationships to determine whether changes are warranted. Not everyone will be severely impacted, he noted, as some local programs do not export any materials. Some are protected contractually against pricing downturns, or they are insulated from the effects because their location makes exporting an unattractive option anyway.