After a year that recorded a notable increase in e-scrap facility battery fires, the growing hazard and ways of mitigating it received ample attention at the Recycled Materials Association’s annual conference in San Diego this week.

In multiple sessions at the San Diego Convention Center, recycling stakeholders from different segments of the industry shared the headaches they face from batteries, primarily the threat of damaged batteries going into thermal runaway and sparking facility fires of all sizes.

“I never expected to be in the battery recycling business, and yet here we are,” said Adam Shine, president of electronics processor Sunnking Sustainable Solutions.

The Brockport, New York-headquartered e-scrap firm doesn’t process batteries in-house, instead packaging them and transporting them to a nearby downstream processor. Nonetheless, Sunnking has an entire team of 12 full-time workers dedicated to identifying inbound electronics that contain batteries.

Currently, battery-embedded devices are the biggest threat, Shine said. It is “very daunting, very time-consuming, very laborious” to get batteries out of these devices, he said.

Nationwide hauler WM similarly deals with battery incidents every single day, said Shannon Crawford Gay, director of recycling and environmental policy for the company. WM has found that small, rechargeable lithium-ion batteries like those in portable power tools are the most troublesome right now, alongside embedded batteries.

Like Sunnking, WM didn’t anticipate becoming a battery handler: “We’re not asking for them, they just show up anyways,” Crawford Gay said.

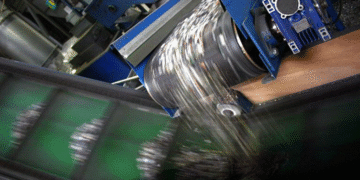

WM is in the process of investing $1.4 billion to automate almost all of its recycling facilities, and Crawford Gay added the risk of losing those facilities to catastrophic fires is not something the company relishes.

Danielle Spalding, vice president of communications and public affairs at battery processor Cirba Solutions, said she’s most concerned right now about the medium-format batteries in e-mobility products like scooters or e-bikes.

That’s because those products are largely imported with batteries made overseas in a variety of markets, where they may be subject to different levels of standards.

Electric vehicle batteries are far easier to handle, particularly because they’re far more visible, noted Derek Corbett, senior vice president of external affairs at Pull-A-Part, an automotive recycling firm. In that sector, the biggest concerns are the cost to harvest batteries versus the value of the resulting commodities and identifying different types of battery chemistries in different vehicles.

But even in the EV world, small-format batteries are a problem.

“It’s pretty hard to miss the six-foot-long, 1,000-pound lithium-ion battery, we can find that,” Corbett said. “But the 48 lithium-ion batteries buried within the vehicle I have? I don’t know where they are, and I cannot get to them.”

Demo highlights sight and smell of thermal runaway

If the speakers’ warnings weren’t enough, attendees got a firsthand look at the threat outside the convention center.

Flanked by members of the San Diego Fire Department, representatives from ReMA and battery stewardship group Call2Recycle staged a live demonstration of a battery fire in an outdoor plaza.

The demonstration featured two 18650 lithium ion batteries, which Call2Recycle’s Eric Frederickson noted is the most common configuration in small-format batteries like those in rechargeable power tools and even electric vehicles.

The batteries in the demonstration were relatively small, totaling 10 to 15 watt-hours, which is smaller than even the batteries in a small laptop or a portable power tool.

Frederickson used a heating element to trigger the process, which starts with the electrolyte in the battery beginning to boil and melt. Soon there was a loud bang — akin to something between a cap gun and a 22-caliber gunshot — and significant smoking, as one of the two battery cells completely exploded. The burning electrolyte material was audible, and flames popped up as the separator within the battery melted. A characteristic burning smell also wafted through the air.

The demonstration fire was relatively small, but Frederickson noted it was certainly enough to set the other recyclables on a tip floor on fire.

Business and policy tools emerge

Efforts are underway to improve battery management both through private sector innovation and public policy development.

Batteries are increasingly part of the discussion of how critical minerals sourcing fits into national security, meaning battery processing is now more than just about diverting materials from a landfill, said Spalding of Cirba.

Cirba processes numerous battery chemistries, including lithium-ion, alkaline, lead acid, NiCad, NiMH and more. The company operates six facilities in the U.S., with a seventh on the way in South Carolina.

There is roughly enough domestic capacity to recycle all end-of-life batteries generated within the U.S. today, Spalding estimated, but in the downstream processing space, the real need is in additional refining capacity. Most refineries are out of the country, meaning at some point the harvested commodities have to cross the border to be made into components suitable for new battery manufacturing.

But perhaps the biggest need is on the upstream supply in improving collection and, most importantly, consumer education. That’s been a major focus for the U.S. EPA in recent years, said Nena Shaw, director of the EPA’s Resource Conservation and Sustainability Division.

The agency has been convening stakeholder meetings discussing labeling standards and collection best practices, but now it is gearing up for an ambitious project in collaboration with the Department of Energy: The two agencies are creating a voluntary battery extended producer responsibility framework covering all battery chemistries, sizes and applications.

One driver is increasing battery EPR laws across U.S. states, leading to an interest in harmonizing such programs on a wider level. Colorado recently sent a battery EPR bill to its governor.

The framework will touch on product design, collection models, reporting requirements and more, and will also provide “sufficient flexibility to allow battery producers to determine cost-effective strategies for compliance with the framework,” according to information EPA distributed at the conference.

Flexibility is key, speakers agreed. Spalding said any regulatory framework needs to allow for independent battery collection and allow for existing processing market development to continue.

Policies should also cover every battery type and chemistry, added Crawford Gay of WM, in an effort to avoid requiring a consumer to identify battery chemistries when recycling devices. As popular battery chemistries change, covering all chemistries would ensure regulations aren’t antiquated as soon as they’re enacted.

Finally, Shine noted that although EPR works in some cases, he’s also seen it turn into a “race to the bottom” in the e-scrap world, with obligated producers seeking the lowest-cost and sometimes least scrupulous operators.

“I want to make sure anyone who is collecting can continue to collect,” he said.

EPA and DOE kicked off the framework development in April and will convene a series of conversations among stakeholders this summer. The agencies tentatively plan to release the framework in mid-2026.

Also at the conference this week:

- ReMA presented the first-ever Billy Johnson Memorial Award, named for ReMA’s late chief lobbyist, to Justin Short, the organization’s director of government relations who has worked at ReMA for 13 years, learning from and working with Johnson.

- ReMA presented a corporate leadership and innovation award to headphones manufacturer Skullcandy for the company’s EcoBuds headphones, which ReMA noted features a battery-free charging case and recycled plastic content.

- ReMA presented a design for recycling award to Samsung for its Galaxy S25, which contains “recycled plastic, aluminum, glass, steel, gold, copper, and rare earth elements” and includes a battery made from 50% recycled cobalt sourced from recycled Samsung batteries, according to ReMA.