Canada-based chemical recycling startup Aduro Clean Technologies expects to select a site for its demonstration plant by the end of the month, the company said in its announcement of results for the financial period ended Nov. 30.

Aduro previously announced it was evaluating an existing site in the Netherlands for a demonstration plant, the next step after its pilot plant in London, Ontario. In November, the company signed a non-binding letter of intent to acquire land, buildings and equipment there for a proposed €2 million ($2.3 million) plus a non-refundable fee of almost €34,000 for exclusive access during due diligence, which ended Jan. 15.

The company reported Q2 2026 revenue of CAD$122,706 (US$88,195), higher by 222% on the year. Year-to-date revenue through Nov. 30 was $167,206 (US$120,180), an increase of 80% on the year. Aduro’s financial year begins on June 1.

Adjusted EBITDA (earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization) for Q2 were negative $3.3 million (US$2.4 million), versus negative $1,887,750 (US$1.4 million) a year earlier. Year-to-date adjusted EBITDA for the six months ending Nov. 30 was negative $5,553,410 (US$4 million) compared to negative $3,634,498 (US$2.61 million) in the prior-year period.

However, the company posted an operations loss of $6.5 million (US$4.7 million) for the quarter, compared to a loss of $3.1 million (US$2.23 million) in the prior-year period. For the year through Nov. 30, the company reported a loss of $12.8 million (US$9.2 million), versus $5.6 million (US$4.0 million) a year earlier. Aduro cited expenses including increased research and development and scale-up of technology, added headcount, and marketing and public relations.

Last month Aduro completed a US public offering of US$20 million and intends to use the proceeds to support the demo plant as well as ongoing R&D and working capital.

Operations update

In September, the company’s pilot plant in London, Ontario, began the commissioning phase, starting with feedstock preparation and testing of reactor systems. In October through December, the company conducted the second phase of commissioning, including product recovery and subsystems.

At its established pilot facility in Europe, Aduro completed steam-cracking trials last fall. The trials produced ethylene and propylene yields similar to those from fossil fuel-based steam-cracker feedstocks, the company said.

Aduro’s Hydrochemolytic recycling process converts lower value waste plastics, heavy bitumen and renewable oils into chemical feedstocks, similar to naphtha, to make new plastics.

The appeal of going Dutch

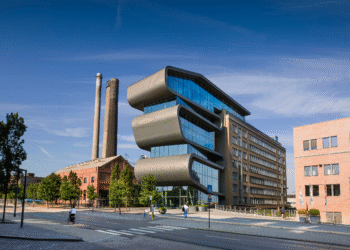

The company is aiming for early 2027 to start up the demo plant. The Dutch site offers existing power, natural gas, water and wastewater infrastructure from its former occupant, a permitted industrial plant. Selecting a brownfield site would reduce risk and required capital, the company said, while expediting the path to start-up. Being located in the Netherlands, the property also offers access to reliable feedstock and a defined regulatory environment, as well as offtake partners.

The country is home to numerous steam crackers that produce ethylene and propylene, the building blocks for most polymers. Although PE by far represents the biggest consumption of ethylene, it also is used to make intermediate chemicals for PVC, PET and PS.

Major producers including Dow, Shell and LyondellBasell own olefins assets in the Netherlands, but unfavorable margins from crude oil-based feedstocks compared with cheaper ethane-derived olefins – and PE in particular – along with aging facilities and high regional energy costs, have pushed companies to prioritize cracker closures in the region.

In the Netherlands, Saudi Arabia’s Sabic announced in 2024 it would decommission one of its 40-year-old Geleen crackers. The plant has a capacity of 550,000 metric tons/year of ethylene, according to data from Chemical Market Analytics, a Dow Jones company. More recently, Sabic divested its European chemicals business to German investment group AEQUITA, which also picked up several of LyondellBasell’s European olefins and polyolefins sites last summer.

In short, a cracker uses high heat to break apart a feedstock molecule – whether crude oil-based naphtha or natural gas liquids such as ethane – to produce primarily ethylene, which is then used to make polymers and other chemicals.