A recent study has focused public attention on household products containing plastic that the authors suggest was recovered from electronics, raising safety concerns about chemicals contained within the recycled content.

Researchers from Seattle-based environmental advocacy and research group Toxic-Free Future and the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam public university this fall published “From e-waste to living space: Flame retardants contaminating household items add to concern about plastic recycling.” The study appeared in the scientific journal Chemosphere.

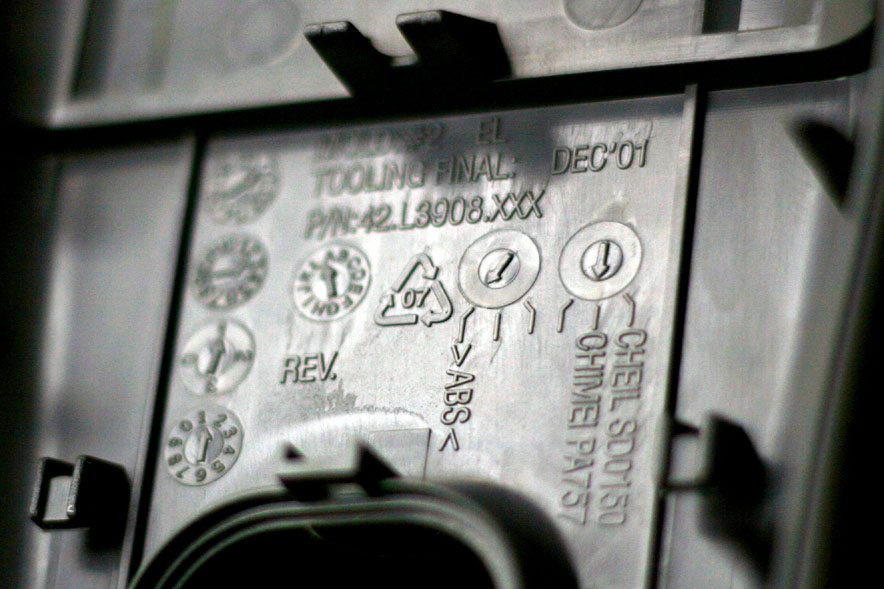

The study looked at common household plastic products that include recycled content, specifically black plastic products that often contain e-plastics, such as acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS), PS and polycarbonate.

These engineered plastics are used in electronics for their durability and often contain additives such as flame retardants. When devices reach end of life, these plastics are typically a low-value material stream with limited end markets, particularly in the U.S., and have historically been baled or shredded and shipped to southeast Asia for processing.

With some exceptions, they mostly are recycled into construction and agricultural products, packaging and durable goods. Kitchen utensils and children’s toys are not typically cited as end markets for e-plastics; in fact, in a 2017 Plastics Recycling Update feature on e-plastics, a processor specifically said e-plastics were unfit for these end uses.

But the recent study suggests e-plastics, and their additives, are also making their way into such concerning uses. The researchers bought a range of black plastic household items, including kitchen utensils, from retailers in 2020 and 2022.

Products were examined with an X-ray spectrometer. Products with a threshold amount of the chemical element bromine, which is frequently used with compounds to create flame retardant chemicals, were further probed for 20 different flame retardants, including legacy chemistries that are no longer widely permitted as well as their replacements.

The researchers examined 203 black plastic products and found 20 of them contained bromine higher than the threshold amount. Of those 20 products, 85% – or 17 products – contained flame retardants, at varying concentrations.

The study can’t say for sure that the recycled plastic came from electronic products, but “the detections of (brominated flame retardants) associated with electronics in these household items suggests recycled content from electronics, such as the black plastic housings, as a likely source of contamination through electronic waste recycling,” the authors wrote.

The findings echo past research that showed additives persist through the e-plastics recycling process and are present in PCR-bearing goods. But the latest study has garnered significant public attention since October, from outlets including The Atlantic, Slate and the Wall Street Journal. Snopes recently evaluated the claims as well.

E-plastics processor perspective

One e-plastics processor that has recently scaled up in Europe told Plastics Recycling Update the study raises important questions about supply chain tracking, but that it also raises some questions.

Pablo Leon, CEO of Spain-headquartered e-plastics recycling firm Sostenplas, noted his company has “never sold recycled e-plastics for food contact applications or toys, and to our knowledge, this isn’t a common practice in the legitimate e-plastics recycling industry in Europe.”

Leon said the presence of flame retardants in black plastics is certainly concerning, but that it doesn’t necessarily indicate plastics recovered from electronics were used in those products. Many of the chemicals found in the studied products are used in other applications, he noted, including automotive parts, construction products and other industrial uses. Additionally, some virgin plastic resin used in the studied products could contain similar flame retardant additives, at least the ones that haven’t been regulated out of use.

“Therefore, linking their presence specifically to e-waste recycling might be oversimplifying the issue and, honestly, quite misleading,” Leon said.

Of the 20 product types with threshold bromine, researchers noted 12 were manufactured in China, and origin information wasn’t available for others. Leon said that is an important distinction.

“This geographic aspect is crucial because different regions have varying levels of manufacturing controls and import regulations,” he said. “In Europe, for instance, regulations like the EU Food Contact Materials Regulation and the Toy Safety Directive make it virtually impossible to use recycled e-plastics in these sensitive applications due to strict contaminant limits.”

EPA rulemaking touches on recycling dynamic

The study authors called for regulations to “prohibit hazardous chemicals in recycled content,” and noted that several U.S. state-level regulations ban some flame retardants in new products, but nothing prevents these materials from entering the recycling stream.

A 2019 U.S. EPA regulation limited the use of a specific type of flame retardant called decaBDE, which was common in TV and computer housings until the late 2000s, when revelations about the chemical’s health effects led to bans in several states. It has been replaced with substitute flame retardants in those electronics applications but is still used in other applications, including wire insulation.

The 2019 EPA rule provided a phase-out period for products that still used decaBDE – but it exempted recycling companies that process that plastic and manufacturers that use the plastic in recycled-content products. A number of environmental groups criticized the EPA for that exclusion, noting the chemical should be banned altogether including in recycled-content products.

The agency defended its decision, saying “EPA recognizes the importance and impact of recycling, which contributes to American prosperity and the protection of our environment.” The agency added that imposing restrictions on recycling plastics containing the additive would be overly burdensome because the decaBDE typically was present at low levels in such articles.

In addition, the agency said if decaBDE were banned, it would be prohibitively expensive to test and manually sort such items from other types of recyclable plastics. The EPA concluded it felt less urgency to regulate these materials in the recycling stream because the agency anticipates their presence would continue to decline, given the move to prohibit them in manufacturing new products.