Wind turbines generate clean and renewable power, but when their blades reach end-of-life, the options – burning or landfilling – aren’t so green.

The wind power industry pulls at the heartstrings of environmentalists, but if the blades go into landfills, “that doesn’t exactly paint a real nice PR picture for the whole industry,” said Karl Englund. “We don’t want to see that happen.”

Englund is chief technology officer for Global Fiberglass Solutions (GFS), a Bothell, Wash.-based company that is hoping to make some of its own green by recycling the blades into pellets and boards. The company has developed – and is scaling up – a plant in Sweetwater, Texas to recycle fiberglass from wind turbine blades and other sources.

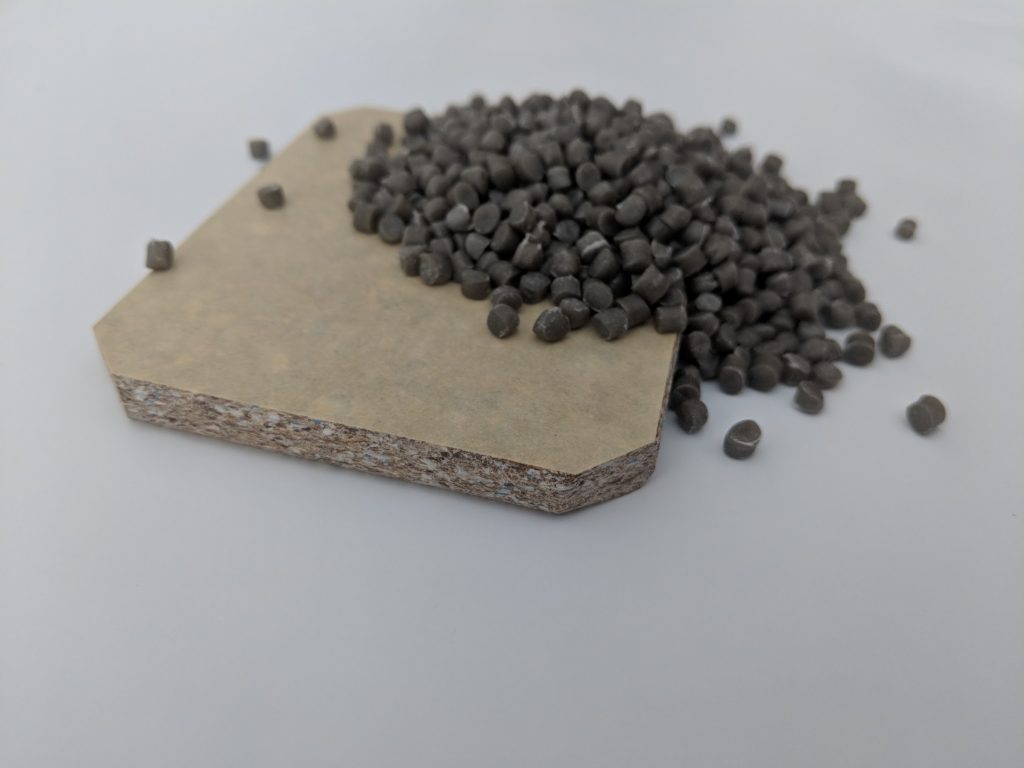

In January, the company began commercial production of its flagship product offering: recycled EcoPoly brand pellets. The thermoplastic fiberglass pellets are suitable for injection molding and extrusion manufacturing processes, according to a company press release.

GFS says it’s the first U.S.-based company to commercially recycle fiberglass wind turbine blades. The company is currently scaling up and plans to boost production capacity by the end of this year.

Tough to recycle

Wind turbine blades present a unique materials recovery challenges, a point emphasized by Veolia, a global utilities and waste management company working to develop recycling solutions for them. Veolia noted they can be crushed and burned in cement kilns, offsetting the need for fossil fuels.

The difficulties start at collection. Blades can be 150 feet long or longer and weight up to 8 tons each. And when decommissioned blades are removed from towers and laid on the ground, their owners often want them collected quickly, Englund said.

GFS has crews throughout the country that collect decommissioned blades from wind farms; most have come from Texas and elsewhere in the Midwest. Blades are generally cut up on-site so they’ll fit on a conventional truck, Englund said.

Generally, fiberglass blades are made of a glass fiber-thermoset composite, he said. They can also contain a core of PS foam, polyurethane foam or balsa wood to reduce weight and alter stiffness. Unlike thermoplastics, thermosets are permanently cured and can’t simply be remelted and molded. As a result, chemical or thermal treatments are used to “cook off” the resin and recover the glass fiber, Englund said. But doing so destroys what was designed to be a strong material.

“We want to keep that inherent strength into the next generation of composites,” said Englund, who works part time for GFS and part time as an associate research professor at the Composite Materials and Engineering Center at Washington State University (WSU) in Pullman, Wash.

GFS uses a mechanical breakdown process to size reduce the blades. Grinding the material is a “very big battle” requiring their expertise, Englund said. Metal bolts and fasteners are removed with magnetic separation equipment. GFS uses gravity separators and air classification separators to sort shredded pieces by size. The particles are usually fibrous, but some have the consistency of powders.

The material is then blended with either virgin or recycled thermoplastics to make a reinforced, filled thermoplastic pellet. The company can adjust the percentage of recycled fiberglass content depending on customers’ preferences. GFS can easily create a 50-50 blend, for example, although GFS expects most customers will want a lower level of fiberglass content, he said.

Generally speaking, the addition of the fiberglass boosts stiffness and sometimes strength, and it reduces thermal expansion, Englund said. On the other hand, it hampers impact strength. Possible end products include decking and siding materials, containers, pallets, parking bollards and more.

GFS is working to develop its own final product. The company’s next product will be composite panel, which is expected to consume most of the recycled material. It can be used in construction and flooring applications, similar to a wood-content particle board. Unlike wood, however, composite panel doesn’t absorb water, making it well suited for marine industries and waterfront facilities, Englund said.

Building a business

Wind turbine blades aren’t just a waste problem in the U.S., they’re also a challenge Europe is confronting. There, stakeholders are less than halfway through the four-year EcoBulk project, which is working to recycle wind turbine blades and other composites used in the construction, automotive and furniture industries.

Founded in 2009 by Don Lilly and Ken Weyant (now deceased), GFS started looking at wind turbine blades as a recycling feedstock five or six years ago. WSU highlighted Englund’s work in 2015, the same year the Bothell-Kenmore Reporter newspaper covered GFS’s plans. In early 2016, Windpower Engineering and Development Magazine wrote a story about efforts by GFS and others to reuse and recycle blades. Englund first joined GFS as 2017 as chief technology officer.

Now, GFS is going through design, engineering, site preparation and air quality permitting for its scale-up in Sweetwater, Texas. The facility is currently capable of processing two or three blades per day, or 2-3 tons per hour on an eight-hour shift. At full production, expected by the end of 2019, the plant will be able to process eight tons per hour.

The company also has a facility in Iowa – although no equipment has been installed yet at that location – and staff in Hong Kong and Germany focused on identifying potential partners, feedstock streams and customers.

GFS leaders see an ample supply of feedstock. Between earlier generations of wind turbine blades reaching old age and government tax credits incentivizing upgrades to more efficient blades, a lot of material is projected to enter the end-of-life stream in coming years, Englund said.

Additionally, the company, in partnership with WSU, is working to commercialize the recycling of carbon fiber composites. GFS helped fund research by a WSU team developing a chemical recycling method for the materials, which are used in the aerospace, energy and other industries.

As far as wind turbine blades are concerned, GFS charges system owners to collect decommissioned blades. The turbine owners would otherwise have to pay for collection and landfilling. Some counties are already banning turbine blades from their landfills, Englund noted.

“The reality of it is there’s not really a lot of options for these guys,” he said.

But GFS is also looking beyond wind turbine blades to scrap fiberglass from boats and planes.

“There’s a lot of stuff going to our landfills right now that are glass fiber composites,” he said. “We’re really focused not just on the wind turbines but all the other fiberglass streams out there too.”

Photos courtesy of GFS.

To receive the latest news and analysis about plastics recycling technologies, sign up now for our free monthly Plastics Recycling Update: Technology Edition e-newsletter.