This story originally appeared in the November 2017 issue of Plastics Recycling Update. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

For U.S. plastic film recycling stakeholders, nothing comes easy.

The material is not generally accepted in curbside programs because it can gum up equipment at materials recovery facilities (MRFs), and in the commercial realm, it has sometimes been overlooked as generators focus their diversion attention on cardboard and other heavier, higher value materials in the stream.

Nonetheless, coordinated efforts within the plastics industry have in recent years greatly increased tonnages of plastic film collected via drop-off, and the best practices developed in successful community campaigns have grabbed the attention of other municipal and state leaders across the country, creating momentum around the material.

Now, however, the sector is facing another daunting barrier. China has been a major destination for much of the film collected in the U.S., and with the Asian giant’s looming ban on the import of post-consumer plastics, including polyethylene, concern is growing that extreme market shortages will affect recycled film, possibly unraveling much of the hard work undertaken by stakeholders.

In short, the race is on to figure out whether domestic buyers can take more of this material.

By understanding how the country’s film collection infrastructure has evolved, the industry may be able to gain insight on how to convene key players to solve plastic film’s market challenges.

20 years of growth in collection

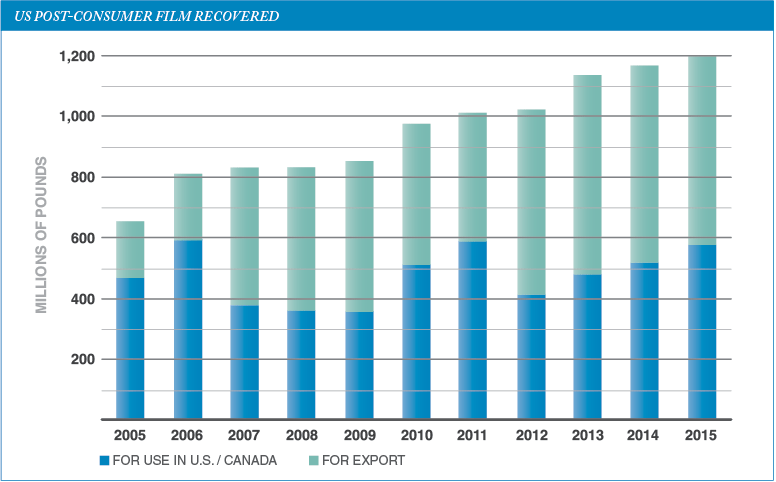

The American Chemistry Council (ACC) defines plastic film as including plastic bags, product wraps and commercial shrink film. Statistics indicate film recycling has made significant progress since the mid-1990s. According to research from consulting firm R.W. Beck, drop-off plastic film programs collected 190 million pounds in 1995. Fast-forward two decades, and the progress is impressive: In 2015, roughly 1.2 billion pounds of residential and commercial bags and wraps were recovered nationwide, as noted in the most recent version of the ACC’s “National Post-Consumer Plastic Bag & Film Recycling Report.”

That represents 84 percent growth since 2005.

At the center of the effort to recover more has been ACC’s Flexible Film Recycling Group and its Wrap Recycling Action Program (WRAP).

The plastics industry has worked with local governments, retailers, processors and others to help efficiently direct loads of recovered film to end users.

WRAP’s mission is to engage and educate consumers and businesses about effective plastic film recycling programs. Working with state and local governments, retailers, MRFs, post-consumer PE haulers and reclaimers, and end-user manufacturers, WRAP aims to expand film recovery through retail drop-off sites so that film does not contaminate curbside programs or end up in landfills.

One of WRAP’s most recent advances has been bringing the state of Connecticut into the program, a step that was made official in February of this year. At that time, a survey showed only half of the Nutmeg State’s residents knew that certain plastic items should be brought to retail sites and not placed in curbside receptacles.

“A driver for us is really wanting to clean up our curbside mixed recycling stream and recognize that it’s more than just telling people ‘no,’” said Sherill Baldwin, environmental analyst at the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection. “It’s informing them about a solution.”

Film collection strategies are being implemented in different ways in different areas of Connecticut.

Some municipalities and retail partners, for example, are switching how they communicate film recycling instructions, relying more on picture- or symbol-based platforms and leveraging the variety of outreach tools offered by WRAP. In smaller communities, where there aren’t participating retailers to collect bags and film, the use of transfer stations as drop-off locations has become more common. Plastic film is then transported to regional participating retailers for baling and hauling.

“We have many rural communities … now able to participate in a way that I wouldn’t have thought they could,” said Baldwin.

Source: American Chemistry Council and More Recycling

Exemplifying collaborative strategy

The program put together in one Connecticut town, East Hartford, helps to hghlight the collaborative approach seen often within the WRAP network, which relies on leaders from state government, commerce and local public works agencies. Before the municipality’s WRAP launch in August, officials in East Hartford, which has a population of just over 50,000, took time to evaluate how best to coordinate the program for the specific needs and temperaments of residents and businesses.

“My philosophy is we don’t go into this alone as a government, but jointly with businesses and the community,” said Marilynn Cruz-Aponte, East Hartford’s assistant public works director. She added that such synergy enables leaders to offer a program that does not come across as “a government mandate.”

In fact, Cruz-Aponte said, the entire effort was designed to build a sense of community as a whole. Her department has been working with East Hartford’s mayor and participating retailers, such as Shop Rite, in executing the town’s educational outreach.

In addition, the East Hartford WRAP team instituted creative educational resources so residents can learn how to best recycle their plastic films. Currently, the town is utilizing social media outreach, radio and local television advertising, signage, mailers, and demonstrations at local events.

“The [key] to expanding drop-off plastic recycling and keeping reuse and waste minimization in the forefront of people’s minds is always adding something fresh,” said Cruz-Aponte.

Knowing they are working with an ethnically diverse population, East Hartford officials also make a point to thoughtfully target their Latino and Spanish-speaking residents.

“One of the things I insisted upon when I met with the ACC and Connecticut Food Association is Spanish-language advertising,” said Cruz-Aponte. “Some people may think people from those countries are not ecology sensitive. What needed to be understood is these are people … who do pay attention to environmental protection.” WRAP leaders note that the group has made a point since its beginning to take steps geared toward multicultural outreach, such as the creation of Spanish-language fliers that participating retailers can use to communicate plastic film recycling steps to Hispanic customers.

Next up for East Hartford is a major waste audit to further evaluate how its continued recycling outreach should be tailored.

Increased program interest

A catalyst for the expansion of the WRAP program into places like Connecticut and North Carolina, where WRAP began working last fall, was strong results from an initiative in Vancouver, Wash. in 2015.

In Vancouver, a city in the Portland, Ore. metro region, WRAP engaged MRF operators as well as city and county staff.

“At the end of the launch campaign we had a 125 percent increase in film recovery and greater awareness by consumers of where and what they can recycle,” said Shari Jackson, an ACC staffer who directs the Flexible Film Recycling Group.

That kind of success has in part been spawned by program guides and marketing collateral created by film stakeholders. Examples include the “Roadmap to WRAP” and “Value Chain Case Study,” each of which walks state and local organizers through the stages of planning, partnership, launch and program sustainability.

“We can’t be everywhere and hand-hold in every place,” said Jackson in describing the value of the “Roadmap” material. “It depicts how you go from A to Z in implementing that sort of program.”

The U.S. EPA has also come on as a coordination partner. The agency has a formal memorandum of understanding with ACC, outlining the entities’ mutual interest in promoting the reduction, reuse, recycling and recovery of plastics. The EPA is working with WRAP officials by helping to expand use of film recycling resources and aiding in development of a system to evaluate program effectiveness.

“EPA plays a convening role with key stakeholders and partners to build cross-organizational collaborations,” noted Jay Bassett, principal adviser for sustainable materials management at U.S. EPA.

Reaching millions of residents

So with all that action by different groups and agencies, what does the film collection landscape look like in numbers?

Stakeholders gathered in February of this year for the launch of WRAP

in Connecticut. Pictured above from left to right are Price Chopper representatives Dave Schmitz, Timothy Frasier and Lee Williams.

According to the ACC, WRAP program outreach has reached more than 12 million residents in 70 communities nationwide. There are now more than 18,000 retailer drop-off locations, and WRAP has a presence in five states: Connecticut, Georgia, North Carolina, Washington and Wisconsin. Programs in California, Kansas and Oregon are on the horizon for WRAP.

More Recycling, a consultant with the ACC and FFRG, issues the “National Post-Consumer Plastic Bag & Film Recycling Report.” In its recent analysis of 2015, the firm determined 52 percent of the nearly 1.2 billion pounds of plastic film recycled and recovered was PE clear film, defined as clean polyethylene film from commercial sources, including stretch wrap and poly bags. Following PE clear film, PE mixed color film, which does not include post-consumer bags, constituted 20 percent of recovered film. And 16 percent of recycled film material was PE retail bags and film, which includes stretch wrap and retail collected post-consumer bags, sacks and wraps.

Though the sector has seen notable tonnage growth, it has its eye on a specific target. “Our primary goal is to double post-consumer film recycling to 2 billion pounds [annually] by 2020,” said Jackson.

To hit that mark, even more coordination may be required. According to a study published this year by recycling consultant RSE USA for the Closed Loop Foundation, groups working to boost film recovery are “in some cases duplicating each other’s efforts, whereas in other cases no one is addressing other obstacles.”

‘Don’t have the domestic capacity’

The more difficult question for plastic film recycling players now: Where will they be sending these increasing volumes of material?

More’s 2015 report indicated 52 percent of post-consumer film was exported internationally that year, predominately to China.

According to a recent Reuters report, China imported more than 7 million tons of post-consumer plastics in 2016, including 2.3 million tons of polyethylene (much of the PE total was rigid material).

It’s little wonder that concerns are running high among film recovery stakeholders as China has moved aggressively this year to restrict the amount and types of recovered plastic allowed for import. In July of this year, China announced it would be banning the import of a variety of recovered materials starting in 2018, including post-consumer plastics like PET, PE, PVC and PS. (For complete details on the trajectory of China’s policy, see our timeline of events.)

Some recycling facilities in the U.S., such as Far West Recycling in Portland, have reportedly stopped accepting film or mixed rigid film because downstream options have become limited. According to the RSE USA study, MRFs have only been able to market less than 5 percent of incoming film because of a lack of domestic and international recycling markets.

“If we are successful getting to 2 billion pounds … I don’t know what we’re going to do with all that material,” said Nina Bellucci Butler, CEO of More Recycling. “We don’t have the domestic capacity to absorb that material immediately.”

With only a few major end market users in the domestic market – including wood-alternative decking manufacturers Trex and AERT – ACC and FFRG and their WRAP partners are assessing the downstream strategy going forward.

Targeted infrastructure investment is one possible path. The RSE USA report noted progress could be seen through development of new wash plants for curbside PE film. More wash plants would “reduce transportation distances and freight costs, and provide additional market capacity” for the existing film that ends up in MRFs but is disposed of. Additionally, facilities need funding for equipment and silos enabling bulk shipment of reclaimed resin, blending and compounding equipment, and high-efficiency dryers, according to the report.

Another compounding obstacle is the market competition with producers of virgin polyethylene resin.

Because virgin PE has been available at lower costs and comparable quality as PCR, many national and international businesses have been leaning toward virgin procurement.

Film recycling proponents have years of work leveraging communication and connections push forward film collection. Those skills will now need to be put to use promoting the value of using recovered material.

“Our focus, because of the restrictions from China on scrap materials, is to help amplify encouragement of buying more recycled materials made from PCR,” said FFRG’s Jackson.

“Through our programs, we’ll put more of an emphasis on buying recycled film and profiling brands, retailers and companies that are stepping up and using PCR material in their own products.

“We’re in the early stages,” Jackson continued, “but I’m certain we’ll be creating more viable options to expand domestic recovery.”

Chris Fleck is a freelance writer and journalist based in Portland, Ore. He can be contacted at [email protected] and cfleck.com.