This story originally appeared in the November 2017 issue of Plastics Recycling Update. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

Meal kit delivery services are a small but growing segment of the food industry. A Google search brings up more than 15 companies vying for attention in this highly competitive marketplace.

Industry leader Blue Apron, founded in 2015, notes it services roughly 85 percent of the U.S. and claims it has delivered more than 159 million meals. HelloFresh, owned by German e-commerce company Rocket Internet, delivers 9 million meals per month in various countries on three continents, according to a Financial Times report. Some analysts, in fact, estimate that meal kit delivery services could evolve into a $3 billion to $5 billion business in the next 10 years.

In meal kits, ingredients for entire meals are packaged together and delivered to consumers’ doorsteps, allowing busy people to enjoy tasty and healthful home-cooked meals without the hassle of recipe planning or trips to the store. But at the same time, meal kit services are bringing increasing volumes of non-recyclable or hard-to-recycle plastics into households. And in some instances, the meal kit companies are implying recyclability without understanding the realities of material processing and markets.

To address this issue, the Association of Plastic Recyclers (APR) recently researched the meal kit mix.

The aim of the project was to better understand the specific components included in packaging and to offer some guidance to ensure these materials actually do get recycled.

A taste of the market

Meal kit delivery services tend to target urban millennials and busy, dual-income suburban residents. Such consumers are thought to be willing and able to pay for the convenience of meals on their doorstep as an alternative to grocery shopping.

Different meal kit brands offer different spins on the concept. HelloFresh, for instance, distributes meals that are simpler to prepare and include fewer exotic ingredients than Blue Apron’s offerings. All the companies in the space source ingredients from a number of outlets, which means a large variety of packaging types are found in the boxes.

In addition, the companies make a point to note their “green” credentials, particularly in the area of food waste reduction. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the U.S. EPA, food waste is the largest contributor by weight to the MSW garbage stream, and meal kit delivery services claim to cut down on these tonnages by controlling all stages of the value chain. Meal kit producers order directly from growers and manufacturers, centralize distribution, cut out the retail store, and provide only the exact amount of food needed to the consumer. Blue Apron says its goal is to waste no more than 2 percent of the food it handles.

Nevertheless, packaging in the sector is beginning to undergo more scrutiny. Critics point to practices such as using an individual plastic bag to contain one stalk of celery or two peeled cloves of garlic. Others have sounded alarms about the waste repercussions of the freezer packs used to keep meal kit items fresh. “They’re big. They’re filled with goo. And they’re rapidly accumulating in a landfill near you,” Mother Jones magazine noted earlier in a feature on meal kit freezer packs.

Some kit companies insulate their packages with PE bubble film that has a metal outer layer.

Packaging concerns have also been voiced by different players in the recycling chain. In 2016, APR began receiving feedback from reclaimers and materials recovery facilities (MRFs) about the insulation materials from meal kit delivery companies showing up in their supply streams. At about the same time, APR started to receive inquiries from some of the meal kit companies themselves – they were asking how they could make their packaging materials more recyclable.

By sampling boxes from three different meal kit delivery services and surveying information provided on the websites of three additional companies, APR staff compiled an inventory of the packaging, evaluated the accuracy and completeness of the recycling instructions provided, and developed suggestions for improving both the packaging and the recyclability instructions.

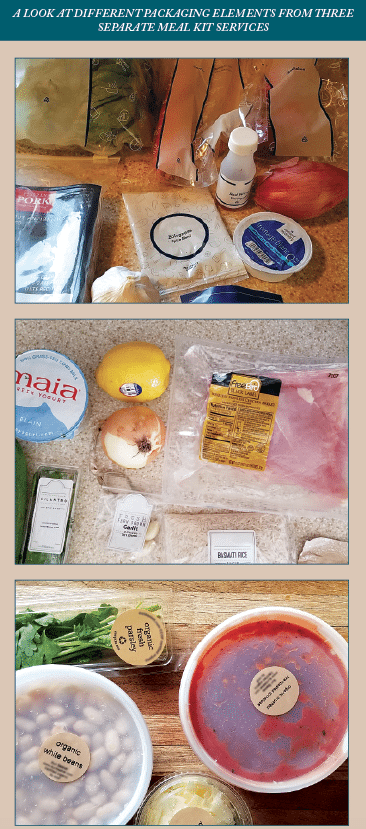

What’s in the box

Meal kit delivery services utilize two distinct types of packaging – the outer delivery packaging and the food ingredient packaging. Delivery packaging consists of the box itself, ice packs to keep the contents cool during shipping and some type of insulation. The food ingredient packaging consists of a variety of containers, along with plastic bags and pouches.

The outside boxes and any inside dividers are universally made of corrugated paperboard and are fully recyclable. It’s the recyclability of the other components that gets complex.

Let’s start by looking at the insulation element. Typically, insulation batts or blankets are 32 to 36 inches long, 11 to 15 inches wide, and about an inch thick. They are folded and tucked in to fully insulate the corrugate box interior and protect the ingredients (see photo).

The various insulation materials employed by the companies reviewed include the following:

- Honeycombed fiberboard with metalized PET foil backing.

- High-loft recycled paper or paper/cotton batting with a kraft paper outer layer.

- PE bubble film with a metal outer layer.

- Recycled PET fiber batting with printed clear PET film backing.

- Jute fiber batting enclosed in a printed clear PE bag.

- Recycled cotton denim batting enclosed in a printed clear PE bag.

According to Byron Geiger at Custom Polymers PET in Athens, Ala., PET insulating blankets from meal kits regularly show up on the company’s processing line. But they are not seen as valuable pieces of feedstock.

Consumers are encouraged to re-purpose ice packs in meal kits, but customers that receive service regularly will likely accumulate far more of the items than they need.

“They end up in our waste plastics,” Geiger said. “They are primarily manually removed, but some come out in our ballistic separator. The negative effect is yield loss. If it does get through our process and is ground, the material is too fine and comes out in shaker screens and aspirators.”

MRFs are also seeing issues with insulation items.

“We pulled one off the front end of the line recently,” Dale Gubbels, CEO of Omaha, Neb.-based MRF Firstar Fiber, said in reference to a piece of the PET fiber insulation. “Our PET market won’t accept it, so if we see more, they too will be trashed.”

While the PE bags in which the insulation is enclosed can be recycled, complications arise when exotic materials, such as recycled denim or jute, are included.

In addition, each meal kit delivery box includes at least one, and up to three, frozen ice packs. These consist of PE pouches filled with a frozen liquid mixture to keep the box contents cold and fresh. They measure approximately 9 to 12 inches long by 5 to 6 inches wide, and about an inch thick.

Two of the six companies investigated advise customers to reuse or donate their ice packs, which is useful advice as they can be reused many times. However, with an average of two ice packs in every box, a customer who gets two boxes per month will accumulate 48 ice packs in a year and probably run out of storage space for them. It’s that reality that has caused Mother Jones and others to voice concerns about the products.

Other than donating, the only recommendation for the ice packs is to thaw them out, discard the liquid inside and recycle the outer bag. A spokesperson for one meal kit company acknowledged the difficulty of motivating consumers to take these steps, especially with the “clean and dry” requirement for all PE recycling.

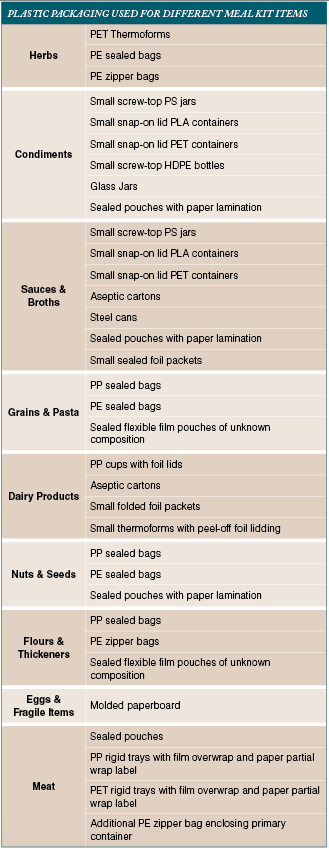

The recycling complexities continue as we get down into the packaging used for the actual ingredients contained in the kits. The table at right illustrates the typical types of packaging used for different ingredient types. This information was gathered from the actual meal kits investigated in the APR research.

The recycling complexities continue as we get down into the packaging used for the actual ingredients contained in the kits. The table at right illustrates the typical types of packaging used for different ingredient types. This information was gathered from the actual meal kits investigated in the APR research.

Here again we encounter a variety of different materials, many of which can technically be recycled but not always so easily when combined in complex packaging solutions or when they are used in packages that are small in size.

The recyclability of plastic components

APR researchers were able to group the plastic packaging used for ingredients into five categories that help to show what parts of the kits can truly be considered recyclable and which should not carry that designation at this time. These determinations were made using definitions from the APR Design Guide for Plastics Recyclability and model bale specifications.

The first category is recyclable flexible plastic packages. These are generally PE bags and film, including bags for products, as well as overwrap on rigid containers that was clean and dry when removed. This also includes zipper-type bags used as additional protection for other packages. The presence of paper labels or printing is considered acceptable. These materials would most likely be accepted in retail drop-off programs.

The second category is non-recyclable flexible plastic products. This grouping includes packaging that came in direct contact with food that was likely to leave a sticky or putrescible residue as well as flexible packaging that was not clearly identifiable as PE (it could be PP or a multi-layer construction).

Third is recyclable rigid plastic containers, which are those items acceptable in most curbside recycling programs due to form, size and resin code, if available. An example is yogurt cups.

The fourth group is rigid plastic containers that are non-recyclable due to size.

And fifth is rigid plastic containers that are non-recyclable for reasons other than size. Examples include packages that had been in direct contact with meat, fish or other highly putrescible contents as well as packages likely to include barrier layers of unknown materials.

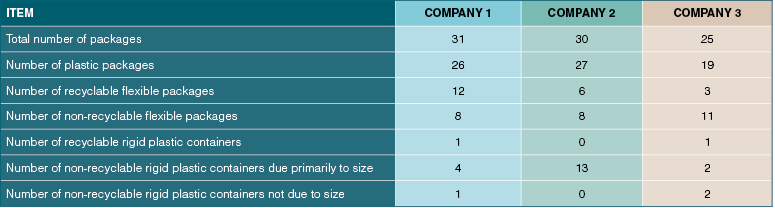

The table below lays out the prevalence of each of the packaging categories in the three meal kits investigated. The data shown in the table indicates that the majority of plastic packages in the kits were not in fact recyclable. The three kits contained a total of 72 plastic packages, and just 23 of those items (or 32 percent) could be deemed recyclable using APR definitions.

While most of the rigid containers are made of recyclable resins, they are too small to successfully travel through a MRF and end up in a bale. The flexible packaging identifiable as PE is acceptable at retail drop-off recycling centers as long as it is clean and dry, but a box will typically contain a mix of flexible packaging that includes polypropylene and multi-material pouches. Consumers are unable to tell the difference and, if they are dedicated recyclers, will likely place all of it in the store drop-off bin.

The meal kit companies nonetheless aggressively promote the recyclability of their packaging through their websites and other advertising. In addition, some recycling information is included in the boxes with the meal contents. Unfortunately, the information provided is often incomplete, confusing or completely wrong.

For example, when it comes to plastic bags and flexible film included in the kits, some companies offer no information at all, others note the items should be clean and dry and recycled wherever No. 4 plastic is accepted, and one company advises users to simply recycle plastic baggies or reuse them. Only one company explicitly directs consumers to store drop-off recycling.

And despite those attempts by meal kit providers to communicate recyclability, the specific properties of the materials have caused concerns among some stakeholders

Blair Pollock, solid waste planner with the Department of Solid Waste in North Carolina’s Orange County, has found himself trying to respond to questions from confused residents who have been assured that their meal kit packaging is recyclable and are frequently unhappy to be told that this may not be completely true.

“Our composter has expressed concern about the claim by one meal mailer that their jute packaging is compostable,” Pollock noted. He said he also has doubts about whether PET blanket insulation in meal kits can actually be successfully integrated into the PET recycling stream, and he’s currently working with a PET fiber maker to test the material to find out whether it’s a viable feedstock.

Ideas that could deliver progress

Based on the recyclability evaluation and feedback, APR has developed a list of recommendations for the meal kit delivery services to improve the recyclability of their packaging and, equally important, to provide better education and outreach to customers.

First, companies should continue to search for better solutions for insulation materials and ice packs, and submit possible products for recyclability testing at MRFs and plastic reclaimers. The PET batting insulation is an innovative and desirable alternative to other throw-away materials, since it is made of recycled PET containers. Other insulation items constructed of recycled denim and jute fibers may be equally environmentally friendly. Additional life-cycle research should be done on these materials.

Further, it’s advisable that meal kit brands use standard packaging whenever possible. For flexible plastic packaging and bags, a variety of resin types and package constructions were found. The current store drop-off collection infrastructure accepts only polyethylene materials and excludes other resins as well as multi-material, multi-layer packaging.

The PET insulation batting used by one company uses recovered PET feedstock, but it’s unclear whether the item can be successfully recycled, despite the meal kit provider’s claims.

Another recommendation is that companies provide accurate, complete and actionable recycling information. Simply claiming that packaging is recyclable is misleading to customers and can lead to wishful recycling with negative impacts. The meal kit company spokesperson said meal kit companies don’t advertise the availability of grocery store recycling options for bags and film because they are in the business of directing consumers away from grocery stores. However, he also noted that even meal kit devotees need toilet paper and other staples, so trips to retail stores are still necessary for most consumers.

In developing their recycling information, meal kit companies should use credible sources. Package designers and suppliers are under pressure to provide sustainable options to their customers, but they are not recycling experts. With the help of qualified recycling stakeholders, the companies can better educate themselves about the important intricacies of the post-consumer recycling collection and processing infrastructure.

Another important notion to keep in mind is that there is real value in continuing to document and promote the sustainability benefits of the meal kit business model, particularly when it comes to food waste impacts. Companies should conduct additional research into the life-cycle impacts of their strategies, and this critical data should be shared, as big-picture environmental gains may offset the impact of some inevitable non-recyclable ingredient packaging.

Finally, the growth of the meal kit model provides a unique opportunity to reinforce recycling behavior among the consumer population. These brands are already becoming experts in using their products to communicate with customers – one meal kit box investigated included an educational storyboard outlining the details of heirloom tomatoes. Perhaps brands could develop similarly engaging messaging about how the kit packaging can be correctly diverted and the journey it may take through the recycling system.

Sandi Childs is film and flexibles program manager at the Association of Plastic Recyclers. She can be reached at [email protected].