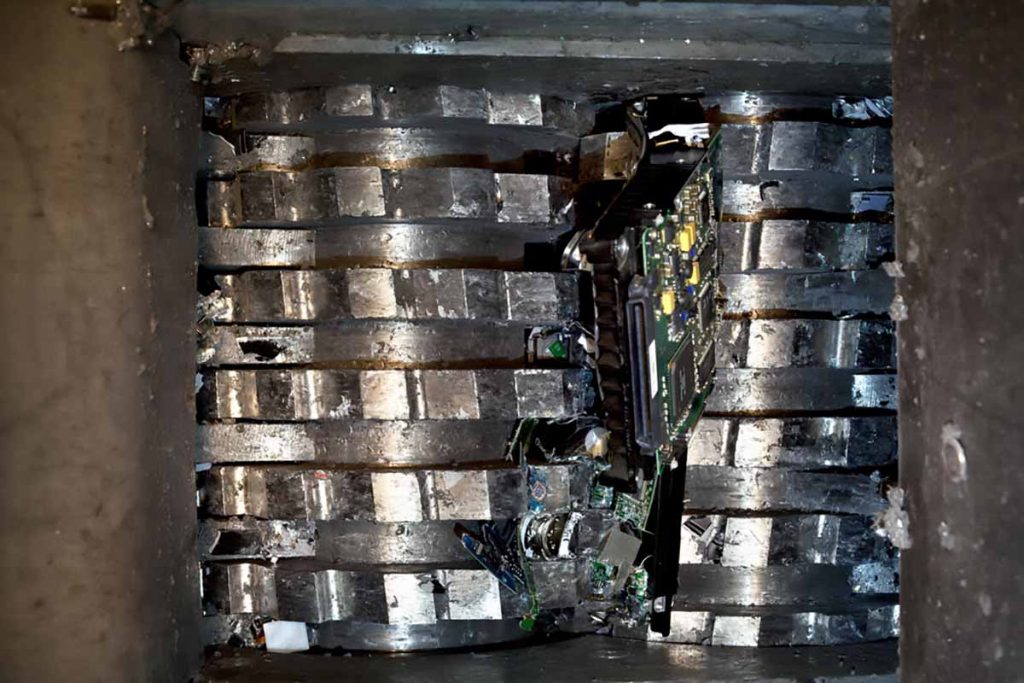

At a recent industry conference, experts emphasized that removing and shredding hard drives may not destroy all data on devices. | Huguette Roe/Shutterstock

A client may ask a processor to destroy their hard drives, but doing so may not accomplish their ultimate goal: protecting the company by destroying all data. That’s because data may lurk in unsuspecting places.

That was a point Luke Westerman of Computer Recycling Center made at last month’s i-SIGMA Conference and Expo, held in Orlando, Fla. Westerman was speaking during a session titled “Capitalizing on the Growing & Transforming ITAD Opportunity.” In the audience were document and electronic media shredding professionals.

“My big concern as an industry, as a group and for you as potential service providers in this world, is that we have a big disconnect,” said Westerman, who is owner and general leader of the Springfield, Mo. electronics recycling company, “because a customer says, ‘Shred these hard drives.’ We take it and shred the hard drives and everybody feels good. But at the end of the day the customer really didn’t mean, ‘Shred these hard drives.’ The customer meant, ‘Take all this equipment and destroy all the data so that it can never harm me.'”

Westerman noted that even after an HD is removed, discs, tapes, SSDs and integrated memory may lurk in a device, holding ample data. With Chromebooks, for example, the memory is integrated onto the circuit board.

Westerman, who is also owner and general leader of mobile document shredding company Big Bear Shredding, said the situation presents a huge risk when data destruction companies send devices downstream to non-NAID-certified recyclers, which could do whatever they want with it. His company is NAID AAA and R2 certified.

“It could go anywhere,” he said. “And so we put our customers at great risk by doing that.”

Also speaking during the panel was Michael Harstrick of Garner Products, a Roseville, Calif. company that produces degaussers and drive shredders. Harstrick pointed out that electronic media present completely different challenges from paper document shredding, given how much data they can contain. For example, at 1.4 terabytes per square inch, if a company shreds the drives to 2 millimeters, each of the 2mm pieces still holds 600,000 pages of data on the surface that could be read with a magnetic force microscope (MFM).

“So the question for your client is how much risk do they want to take?” he said. “If they don’t degauss it, you cannot get this small enough to make this safe. It’s that simple.”

The third panelist was Jason Teliszczak of Orlando-based JT Environmental Consulting, which assesses clients to help them achieve standards, including NAID AAA certification. He noted that even if a data destruction firm sends equipment out the door with residual data, sending it to an R2- or e-Stewards-certified recycling facility will offer protection. That’s because those standards also touch on data security.

“They’re going to have a little bit of data in their background, so in case you botched, you missed something simple, it’s nice to go to someone like that because they’ll kind of swoop in behind you, kind of cover your butt,” Teliszczak said.

Harstrick also noted the fire risks present – but not always obvious – in shredding electronics. For example, manufacturers are embedding watch batteries to power SSDs now, because there’s so much happening with the drives that even a power flicker can be a “catastrophe.” But shredding SSDs without first removing the batteries can trigger a fire.

He noted that it’s time consuming – and thus, expensive – to take apart a KVM motherboard (KVM stands for keyboard, video, mouse, and it’s a motherboard that allows a user at one terminal to control multiple computers), and that they can contain three watch batteries.

Despite the complexities of destroyed information on electronics devices, Westerman said he feels document shredding companies wanting to enter the business have a distinct advantage over e-scrap recycling companies. That’s because document shredders have so many more frequent “touches” with customers than e-scrap companies, which “end up in more of a purge business.” He thinks they can pull 80% of the value from 20% of the efforts electronics recycling companies are putting out.

“So, to leverage that relationship with the right person already, you have such an advantage over all of us traditional electronics recycling people right out of the gates,” he said.

More stories about data security

- Data sanitization helps reduce premature device destruction

- Iron Mountain sees ITAD surge, raises forecast on record Q2

- Data erasure firm expands wearable device capabilities