Electronics processors are increasingly adding solar panel recycling capacity, in some cases processing the panels similarly to declining streams like CRT glass and in other cases rolling out entirely new technologies, companies said in recent interviews.

E-Scrap News several years ago profiled how a handful of processors are handling solar panels and recently checked in with new entrants to the market and emerging technology developers.

As panel processing has grown in the e-scrap field, the R2 certification standard recently rolled out a photovoltaic panel-specific processing certification appendix, and two processors have achieved that certification.

Using solar glass to replace declining CRT volumes

The first company to achieve R2’s new certification solar annex was Carol Stream, Illinois-headquartered Com2 Recycling Solutions.

Com2 has been processing CRT glass since 2009, using the crushed leaded glass to create frit material, a ceramic powder that is used in tile manufacturing. The company is still shipping its frit every month, but Com2 is processing roughly 60% less CRT material than it did just two years ago, said Saheem Baloch, vice president of Com2.

Meanwhile, “we have the buyers who want to continue this frit,” he said. So Com2 entered the solar panel recycling game in 2023 based on its ceramic customer base and increasing inquiries from suppliers, Baloch said.

“We tested glass from the solar, and it turned out to be a good match for our frit,” Baloch said. Solar panel recycling is “really pretty easy” when compared to CRT glass processing, Baloch said: There’s no lead in the panels, for instance, and the hardest part is separating the wafer material from the glass.

Com2 sources panels from solar installation contractors, from other recycling companies who don’t process the panels and from manufacturers. Very occasionally, they come in from residential drop-off.

Like every company E-Scrap News spoke with, Com2 is charging an upfront fee to process the panels due to the low value of extracted materials.

“The recovered value is not enough to cover the cost,” Baloch said.

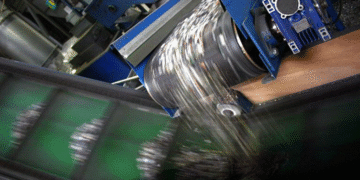

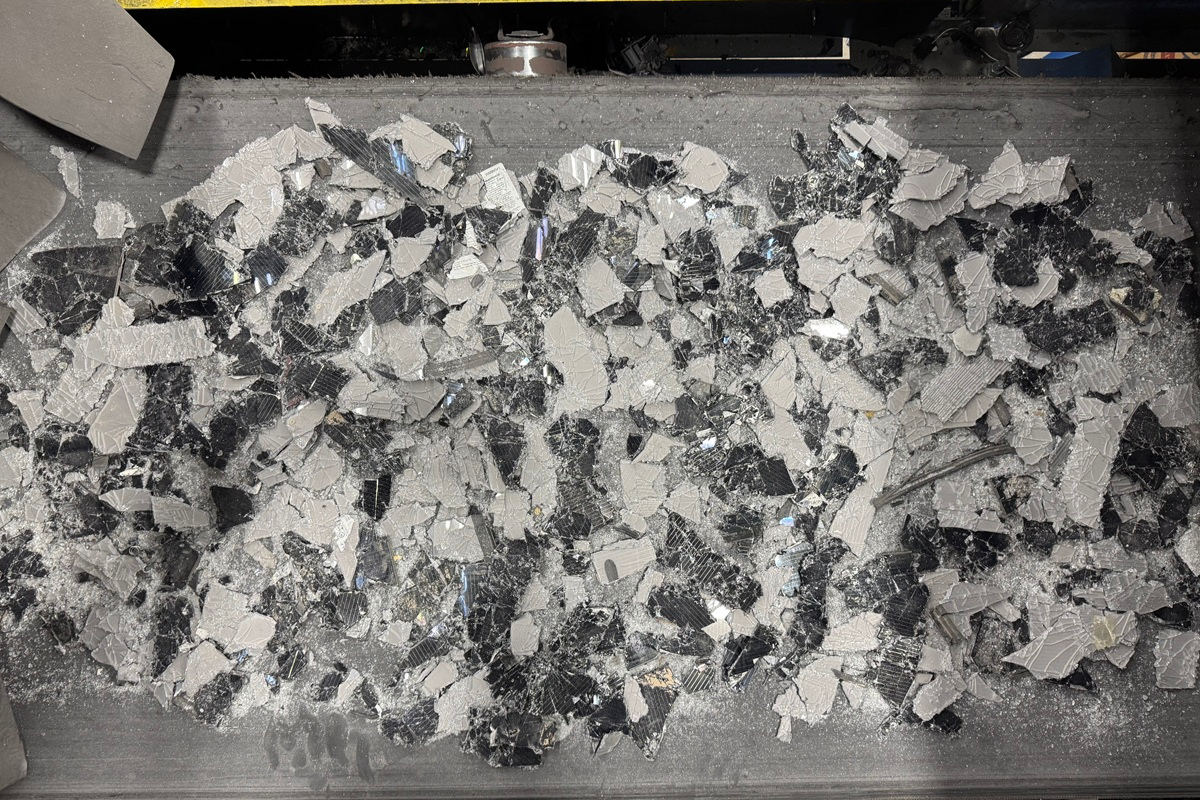

When the panels arrive, Com2 first separates the aluminum casing from the glass panel. The aluminum can be sold for scrap. The panel then goes to an initial crusher line, where it is reduced into smaller pieces, then into a glass pulverizer. The pulverizer produces a fine stream of glass, silica, copper and other metals.

The crushed glass goes to the company’s frit line, where it’s mixed with CRT glass to create the frit output. The solar glass fits well into the frit mix, but the volume is too low to create a solar glass-specific frit at this point, Baloch noted. The company is processing between 8,000 to 9,000 panels each month, he said, and in an average solar panel, the company might recover 13 or 14 pounds of glass.

“We have to mix with some glass, either the CRT glass or other bottle glass, to make the volume” to send to the ceramic buyers, he said.

Volume on the rise

While Com2 may not be receiving a large enough volume to make a frit entirely from solar-sourced glass, the volumes are growing. That’s despite the fact that solar panels have a fairly long life, typically multiple decades.

By 2022, the National Renewable Energy Laboratory noted there were “a large volume of PV modules in the United States being retired after only 10 to 12 years in service, long before the life expectancy of 25–30 years.” The lab relayed anecdotal evidence that this was caused by a combination of early retirement, due to more efficient new panels coming on the market, and of extreme weather damage.

The lab added there was already a “growing stockpile of early-retired modules” in the U.S.

Just how many solar panels are currently available for recycling is difficult to estimate — NREL noted there is no realistic way of quantifying the size of the stockpile. But its 2022 study cited figures suggesting that by 2030, there could be about 43,000 metric tons of panels cumulatively in the U.S. end-of-life stream.

The same end-of-life model projected a cumulative 6.5 million metric tons of panels will reach end of life in the U.S. by 2050. Globally, that figure is an estimated 80 million metric tons by 2050, NREL reported.

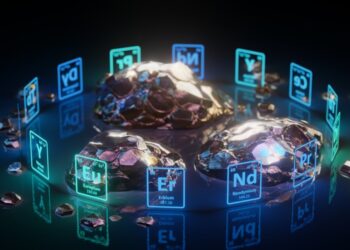

In the U.S., that estimate breaks down to about 5.2 million metric tons of end-of-life glass, 250,000 metric tons of silicon, 3,000 metric tons of silver, 4,000 metric tons of copper and 900,000 metric tons of aluminum.

By 2050, the estimated cumulative value of material recoverable from end-of-life solar panels is about $15 million, NREL reported, and the recoverable material could provide enough raw feedstock to produce 2 billion new panels.

NREL concluded that end-of-life solar management “will become both a critical challenge for the expanding solar industry and an environmental, economic, and social opportunity.”

More capacity coming online this year

A growing list of companies are seizing the opportunity.

Just this month, Nevada-based Comstock Metals announced it has also achieved the R2 solar panel-specific certification, joining Com2. In a statement, the company said it “demonstrated panel processing with proprietary thermal methods, producing 100% commodity-ready products. All parts of the panel, including glass, aluminum, and fines, are fully recycled.”

Comstock commissioned its Silver Springs, Nevada-based solar recycling center in January 2024, and it’s currently capable of processing 132,000 panels per year, equaling out to about 4,000 metric tons of panels.

The company is currently planning an ambitious expansion, aiming to hit 3.3 million panels per year — 100,000 metric tons per year — of capacity in 2025.

Another company planning a 2025 solar scale-up is PedalPoint Recycling, the U.S. electronics processing subsidiary of Korean metals giant Korea Zinc. PedalPoint is currently processing panels, working with solar manufacturers and installers and using its own downstream of Korea Zinc’s refinery.

“In the first quarter of 2025, PedalPoint continued to scale its solar operations by working with key solar developers and manufacturers across the country,” the company said in a written statement.

“PedalPoint’s solar recycling platform is designed to handle not only intact, decommissioned solar panels but also broken, damaged, and scrap-cell materials,” the company added. “Through a specialized process, aluminum frames and glass are carefully separated and recovered, while remaining components containing silver and copper are sent to Korea Zinc for final extraction.”

In Korea, the company refines the silver and copper to purity levels of more than 99.99%, it said, and the output metals are sold as raw material to produce the thermally conductive silver paste that is used in new panel manufacturing.

Other prominent solar processors include Solarcycle, which has received investment funds from Closed Loop Partners, as well as We Recycle Solar, ERI and First America.

Layer-by-layer milling for chemically-intact streams

In California’s Inland Empire region, PV Circonomy, a spinoff of a Taiwanese university, is an early-stage company scaling up a technology that takes each panel apart layer by layer, as opposed to crushing it first and then separating out the commodities.

Terry Ko, chief operating officer, told E-Scrap News the hardest part of the solar recycling process is separating the polyvinylidene fluoride backsheet from the glass. A panel’s backsheet protects the panel from moisture damage and other degradation and is difficult to remove because it’s not elastic, Ko said.

Once the panel is crushed, removing the backsheet from the crushed stream involves either thermal or chemical processes. Ko’s company separates the backsheet before any crushing, removing the polymer material and actually selling it as a feedstock for new materials like plastic piping.

PV Circonomy uses an artificial intelligence-equipped system that scans and documents the layer thickness of each panel and shares that information with subsequent milling machinery. The company has two milling modules that take off a precise layer of the coating. The milling machinery is about 40 feet long, the size of a standard shipping container.

The company separates other layers as well, including the encapsulant between the backsheet and the silica solar cells, typically made from ethylene vinyl acetate — EVA — and then the encapsulant between the solar cells and the protective glass. The milling equipment essentially scrapes off and then vacuums up the recovered material.

“We separate all of them out,” Ko said, noting that certification firm SGS verified the company’s process recovers 99.3% of material in a panel.

It’s a slower process than crushing panels en masse – the system can handle roughly one panel per minute, Ko said, and the company has run trials using up to 100 panels in a row with success.

The company’s process takes place at room temperature, which is important because it doesn’t change the chemical composition of the raw materials, Ko said. That enables the company to provide EVA, for example, as a feedstock for new products including shoe soles, yoga mats and mousepads.

Glass-focused processor draws equity investment

Meanwhile, in Jacksonville, Florida, emerging processor OnePlanet Solar Recycling recently received $7 million in capital investment from a New York investment firm.

The company was founded in early 2024 by a group of solar stakeholders including renewable energy, technology and metals recycling experts, CEO Andre Pujadas said in an interview. The company’s Jacksonville-area pilot facility has a capacity of about 500,000 panels per year.

The company is in the process of building up a facility near its pilot plant in Green Cove Springs, Florida, where it plans to process 2 million panels per year at commercial scale.

Its process uses a combination of technologies that are typically geared toward the mining and heavy media industries. OnePlanet performs a lot of pre-processing using AI imaging and advanced sensor technology to assess panel condition and move panels to the proper stream based on physical integrity, material composition and other attributes.

The company is heavily focused on glass removal efficiency, Pujadas said, with a proprietary process it developed with engineers involved in solar panel manufacturing.

OnePlanet brings in panels from a variety of sources, including decommissioning projects and partnerships with solar farms. In 2024, Florida was the third largest state by installed solar capacity, according to the Solar Energy Industries Association. There is a “readily available substrate” of end-of-life solar panel supply in Florida, Pujadas said.

Additionally, “Florida, being in a hurricane zone, there are a lot of events where hundreds of thousands of panels are destroyed,” Pujadas said, echoing the NREL analysis of shorter-than-expected lifespans.

OnePlanet is planning two additional facilities with the same capacity for a total of 6 million panels per year of processing ability by 2030. The other two facilities have not yet been sited.

“It will be in an area where there’s a high concentration of solar installations,” Pujadas said. “It could be in Florida, Texas or California. Raw material is very important, the concentration.”