With domestic demand building slowly, U.S. processors must look to industries outside electronics manufacturing to absorb their e-plastics volumes, according to panelists at the recent E-Scrap Conference in Orlando.

Since North America offers little in the way of electronics manufacturers who might buy recycled e-plastics, the automotive sector in Asia and Mexico is a key area of growth, especially for ABS and PP, said panelist Zhan “Bo” Zhang, director of BoMet Polymer Solutions. Japan and South Korea are among the top five countries for automobile production, for example, and they sell to Europe, which has upcoming mandates that new vehicles contain 25% recycled plastics.

Extending U.S. mandates beyond beverage bottles and into other industries could enable e-plastics processors to expand, added Hong Yoon, CEO of Hanil Eco Solutions, based in Southern California.

South Korea has a relatively small and stagnant population and thus a small supply of old vehicles, Yoon said. In addition, Korea does not shred used vehicles, opting instead to sell them to Russia and other countries. As such, Korea has a limited supply of PCR.

Meanwhile, the U.S. has a vast supply of used vehicles destined for shredding, Yoon said: “I want recyclers to understand that the material you’re shipping to Malaysia and other parts of Asia will be a strategic resource in the future that you have control of.”

Profit vs. morality

Although e-plastics have untapped recycling potential, recovering those materials can usher in regulatory and morality issues, the panelists said during the Oct. 1 session.

Almost all material is capable of being recovered, but problematic ingredients in the plastics such as bromine can hinder recycling. Because only 40-60% of recovered e-plastics are recyclable, yields from end-of-life devices are poor and recycling economics are unfavorable.

The plastics currently recovered are within safe limits for hazardous materials in the U.S., said Yoon. Other regions have a market for those materials because they’re not as heavily regulated as in the Western Hemisphere, he said, adding that most of the plastics Hanil handles are from devices made decades ago before the regulations were in place.

Processors must consider the morality issue versus the economic benefit, he said, citing a recent recall of children’s items in Asia that contained excessive levels of hazardous materials from plastics. Although such regulations have clear public health benefits, they do mean it’s impossible to hit 100% recovery rates.

Tidying up post-consumer streams

As for current recovery streams, the plastics processors on the panel agreed that they would like to see cleaner, more segregated e-scrap streams to help improve profit margins as well as yields. Yoon said Hanil also tries to find ways to recover more e-scrap so the onus isn’t only on feedstock suppliers.

In the EU, extended producer responsibility laws have definitely helped clean up recycling streams, said Pablo León, CEO of Spain-based e-plastics processor Sostenplas. This has made feedstock volumes more homogenous, though countries vary in collection practices, he added.

Nevertheless, upstream processors may not know what U.S. e-plastics recycling firms are looking for in regards to quality, said Clive Hess, president of ITAD processor CompuCycle.

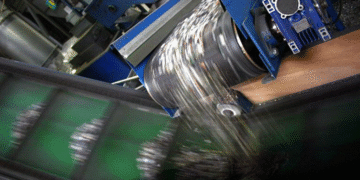

“What we consider clean material is not clean material,” he said, using the example of printers shipped with paper and ink cartridges still inside. Hess described CompuCycle as a relative newcomer to the industry. It upgraded its six-year-old Houston plant with a float-sink system in November 2023 and in July 2024 added an electrostatic system to separate out ABS, PS, PE and PP.

Capacity vs. demand

As in any recycling market, debate continues as to which is needed first: more capacity or more demand.

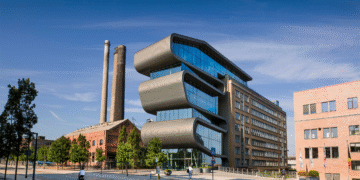

The U.S. does not necessarily need to add capacity for processing post-consumer ABS and HIPS, said BoMet’s Zhang. BoMet has two facilities: one in Ontario, south of Toronto, and the other in Buffalo, New York. Yoon concurred, saying that his plant is running hard but still has room to accept more e-plastics.

Hanil will try to serve as many customers as possible before declaring a need for more capacity, Yoon said. But so far, “we have never been full enough to run three shifts a day, seven days a week.”

For about 30 years, there was no discernible market for recycled e-plastics, Yoon said, due to minimal applications for post-consumer ABS and HIPS. After 2020, though, the tide started to shift. North America is a net importer of virgin ABS, and domestic end users were stymied by pandemic-related supply chain disruptions. As a result, buyers turned to domestic recycled ABS, he said, and “this is how we found the market.”

However, since 2022 mechanical recycling companies have faced stiff competition from off-grade virgin resin, the material produced when starting up a new polymer plant. For example, numerous new PE plants have started up in both the U.S. and China in the past two years, flooding the market with virgin materials and pressuring down prices at times to half the cost of recycled resin.

Lessons learned from Europe

A major roadblock for recycling of any plastic in the U.S. is the lack of mandates.

European EPR schemes have contributed to material getting recycled, Leon said, but in the U.S. demand may lag because end users think there is no supply. But if no one recycles ABS, for example, there will be no demand for it, either.

In addition, in Europe recycled plastics have been available for decades, so the manufacturing industry is accustomed to using PCR, he said. Demand “is not something you build in one or two years.”

Zhang said that in the next three to four years, interest will grow but uncertainty will remain, including upcoming implementation of amendments to the Basel Convention, whose regulatory effects on supply are yet unclear.

Hess said processing e-plastics has to become more economical, as domestic costs are currently far higher than international. “There’s a very large supply of our product,” he said. “We just need to be able to process it economically.”