Sending battery-containing devices through the shredder is typically a no-no for several reasons, but manually removing and taping batteries prior to shredding the rest of the device is labor intensive. A newly unveiled processing system addresses the conundrum.

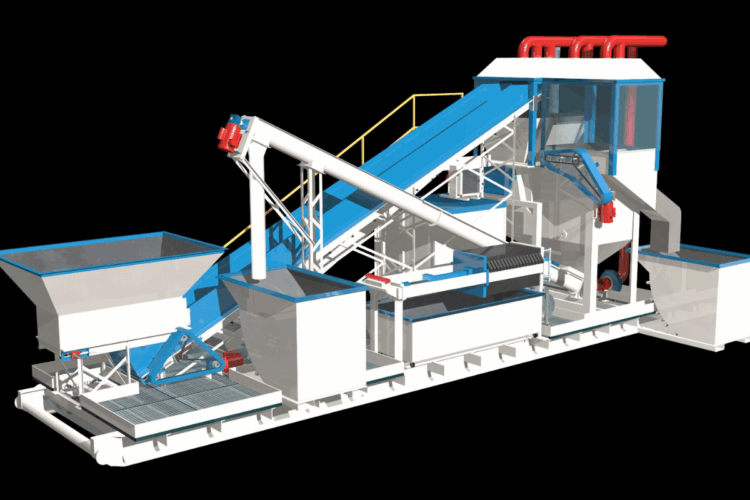

Gloyd Recycling Solutions, in partnership with Archimedes Industry Advisory and Investments (AIAI), in December announced their Battery-In-Device-Shredder system, model 23 (BIDS23). The system shreds battery-containing devices and sorts materials into three fractions, based on their density: plastics, metals and black mass.

Jeff Gloyd, founder of Gloyd Recycling Solutions and a partner at engineering consulting firm AIAI, said after batteries and battery containing devices are separated from bulk feedstock, the intentions are to allow facilities to avoid the labor needed to remove batteries and tape terminals and to reduce fire risk associated with storing and shipping batteries. The system, which includes a wet shredder and an emissions scrubber, safely shreds batteries, removes hazardous gasses emitted from them and recovers the commodities.

“I truly believe that something like this can change the status of recycling electronics today,” said Gloyd, who noted the proliferation of batteries in new device types and in devices that previously didn’t have them. “There’s more of this material and there needs to be a solution that reduces risk to facilities and staff and allows warehouses to operate more efficiently. I’m hoping this system can be part of the solution.”

Battery market requirements drive R&D

Two years of research and engineering went into developing BIDS23, Gloyd said. It was driven by the need to solve a pervasive problem in the e-scrap industry.

Downstream recycling outlets for batteries mostly consist of large-scale facilities that want big volumes of sorted batteries, with a hefty appetite for large and metals-heavy electric vehicle (EV) batteries. Those outlets are not as interested in the multitude of small-battery-containing consumer devices in the end-of-life stream. In addition to computers and mobile phones, that stream includes earbuds, e-cigarettes, toys and other small electronic items.

“We’re throwing this stuff away in record numbers, inside record numbers of devices, and that’s where I’ve seen the challenge within our industry,” Gloyd said.

Existing battery recycling outlets don’t like the lower metals content and the presence of non-desired battery chemistries and organics in consumer electronics battery recycling, Gloyd noted. As a result, upstream suppliers are faced with finding battery containing material, then manually removing batteries from devices and sorting and taping them, with little to no value proposition.

And even if workers are 100% accurate at removing batteries from devices, the fact that the batteries are then stored en masse presents a risk of potentially devastating fires, Gloyd noted.

Designed for relatively low volumes of up to 1 ton per hour (depending on the feed streams), the BIDS23 system uses a small wet shredder, followed by a density-modified water tank to sort the shredded output into three streams. The plastics and other light materials float, the metals (steel, aluminum, copper and circuit boards) sink, and the black mass (shredded batteries) becomes a slurry suspended in the water. The system, which recirculates the water, recovers all three fractions.

BIDS23 also has a proprietary wet scrub emissions control system that captures off-gassing from battery shredding.

BIDS23 requires 1 or 1.5 full-time-equivalent employees to operate, Gloyd estimated. The system is delivered on a semi-truck trailer and is ready to go after it’s bolted down, plugged in and filled with water, he said.

“It’s an incredible value from a plug-and-play perspective,” he said.

Lead times are currently about six months from purchase to delivery, he estimated.