This story originally appeared in the September 2016 issue of E-Scrap News.

Subscribe today for access to all print content.

Local governments play a central role in providing electronics recycling opportunities to citizens in North Carolina. Their efforts help divert materials away from disposal and into the electronics recycling economy.

In fiscal year (FY) 2014-15, 93 of North Carolina’s 100 counties and 16 North Carolina municipalities reported operating public electronics programs. Some of those local governments started electronics collection programs in the early 2000s, but many others only started collection efforts with the passage of North Carolina’s electronics law and the state disposal ban on televisions and computer equipment that became effective on July 1, 2011.

Collectively, these programs recycled 10,026 tons of televisions and 5,051 tons of computer equipment and other electronics during FY 2014-15. The full range of devices covered by the state’s electronics management program includes televisions, computers, monitors, printers, scanners and combination print-scanner-fax machines. Those items are also banned from disposal in the state.

But in the short time period since those 2014-2015 numbers were tabulated, the electronics recycling landscape shifted in notable ways, with revenues from commodities falling and costs increasing to handle some material types. This article presents the results of an early 2016 North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) survey to better assess public electronics recycling in North Carolina. The survey sought information on program operations for both FY 2014-15 and the first half of FY 2015-16, and it included questions about programmatic costs and materials handled.

Data from the survey revealed that even with recent cost increases, the provision of public electronics recycling remains relatively affordable on a per-citizen basis.

Interplay between flat panels and CRTs

The 64 governments that responded to the survey manage 292 individual collection sites across the state, and every program surveyed indicated accepting all of the electronic equipment covered by the state’s disposal ban.

Some programs limited their collection to the statutory materials, and others accepted additional types of electronic equipment that, while not banned from disposal, have been proven to be readily recyclable. Such material includes keyboards, mice, cellphones, stereo equipment, telephone equipment, VCRs, DVD players, wires and cable, and photocopiers.

Some programs limited their collection to the statutory materials, and others accepted additional types of electronic equipment that, while not banned from disposal, have been proven to be readily recyclable. Such material includes keyboards, mice, cellphones, stereo equipment, telephone equipment, VCRs, DVD players, wires and cable, and photocopiers.

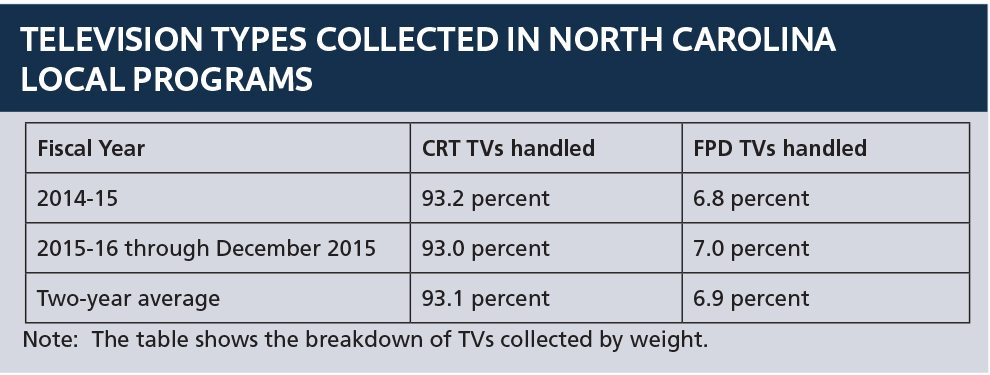

Television recycling has been a high-profile challenge of late as costs have risen to manage these materials. Survey results indicate that flat-panel display (FPD) televisions represent 7 percent of the televisions recycled by weight, and CRT televisions account for 93 percent of the televisions managed (see table above).

It appears that the percentage of FPD televisions relative to CRT televisions is gradually increasing.

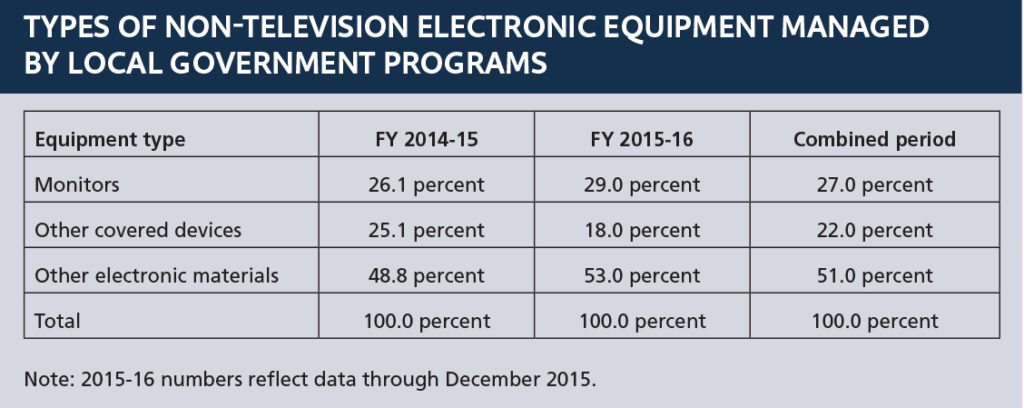

Looking beyond televisions, computer monitors represent just over a quarter of the non-television equipment collected by weight, other covered devices make up just under a quarter, and approximately half of the remaining material collected by public programs is not covered by the state disposal ban. The collection of equipment beyond the statutory materials indicates a strong desire among cities and residents to divert a wide range of electronics from disposal

Looking beyond televisions, computer monitors represent just over a quarter of the non-television equipment collected by weight, other covered devices make up just under a quarter, and approximately half of the remaining material collected by public programs is not covered by the state disposal ban. The collection of equipment beyond the statutory materials indicates a strong desire among cities and residents to divert a wide range of electronics from disposal

As shown in the table below, the survey revealed that televisions make up around 60 percent of the total weight of materials handled by community programs in the state.

Where costs are incurred

Where costs are incurred

Survey responses on program cost demonstrated two broad categories of expenditure: expenses paid to electronics recyclers, and expenses paid to establish and operate collection services.

The economics of electronics recycling is closely connected with the recovery of commodities, such as aluminum, steel, copper, plastic and precious metals including gold, palladium, platinum and silver. Of course, in addition to containing valuable materials, electronic equipment also contains toxic materials such as lead, mercury, beryllium, cadmium, brominated flame retardants and a variety of batteries containing heavy metals.

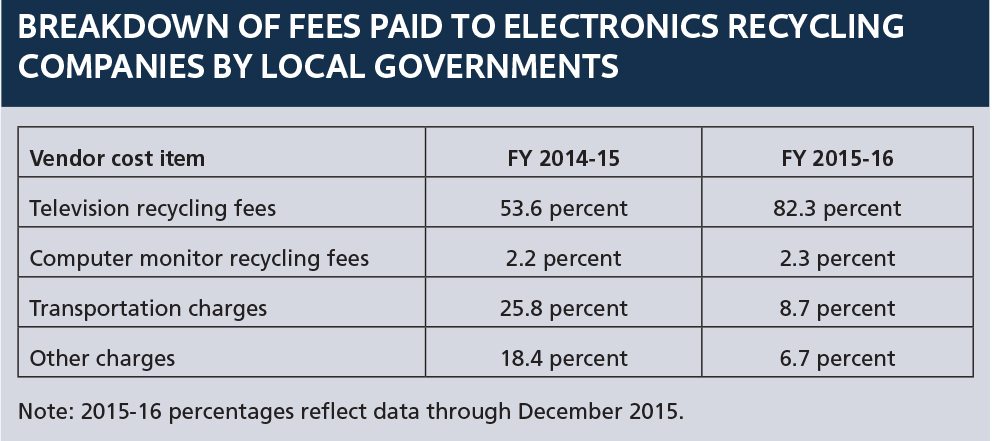

As the value of a wide range of commodities associated with the electronics stream has declined over the past two years, revenue became less available to help offset the cost of managing the difficult to handle materials. This situation has become especially acute for televisions, a change felt most particularly by North Carolina’s public recycling programs. The table here provides a look at the increase in fees paid by survey respondents to their electronics recycling companies during the survey period.

As the value of a wide range of commodities associated with the electronics stream has declined over the past two years, revenue became less available to help offset the cost of managing the difficult to handle materials. This situation has become especially acute for televisions, a change felt most particularly by North Carolina’s public recycling programs. The table here provides a look at the increase in fees paid by survey respondents to their electronics recycling companies during the survey period.

The expenses noted for FY 2015-16 only reflect payments to electronics processors for a portion of the fiscal year, and when projected across the full fiscal year it is estimated that total payments to electronics recycling contractors will have increased more than five-fold over the previous year.

These payments to electronics recycling contractors cover a range of services such as collecting and transporting materials, processing different types of equipment, and charges for supplies such as boxes and shrink wrap. Survey responses break down the types of expenditures paid to electronics recycling companies, revealing the single costliest element to be fees for television recycling.

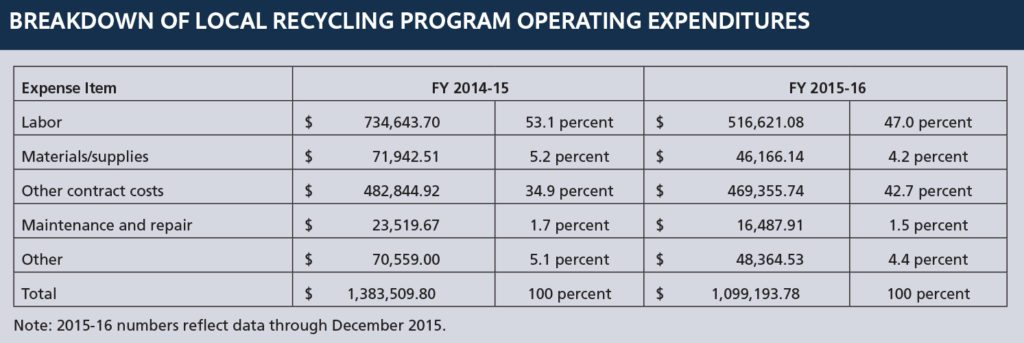

Survey results displayed on the table above also demonstrate a range of additional local government operating expenses, including labor for materials handling and program management as well as costs for program supplies, maintenance and repair for trucks and equipment, and fuel and utilities.

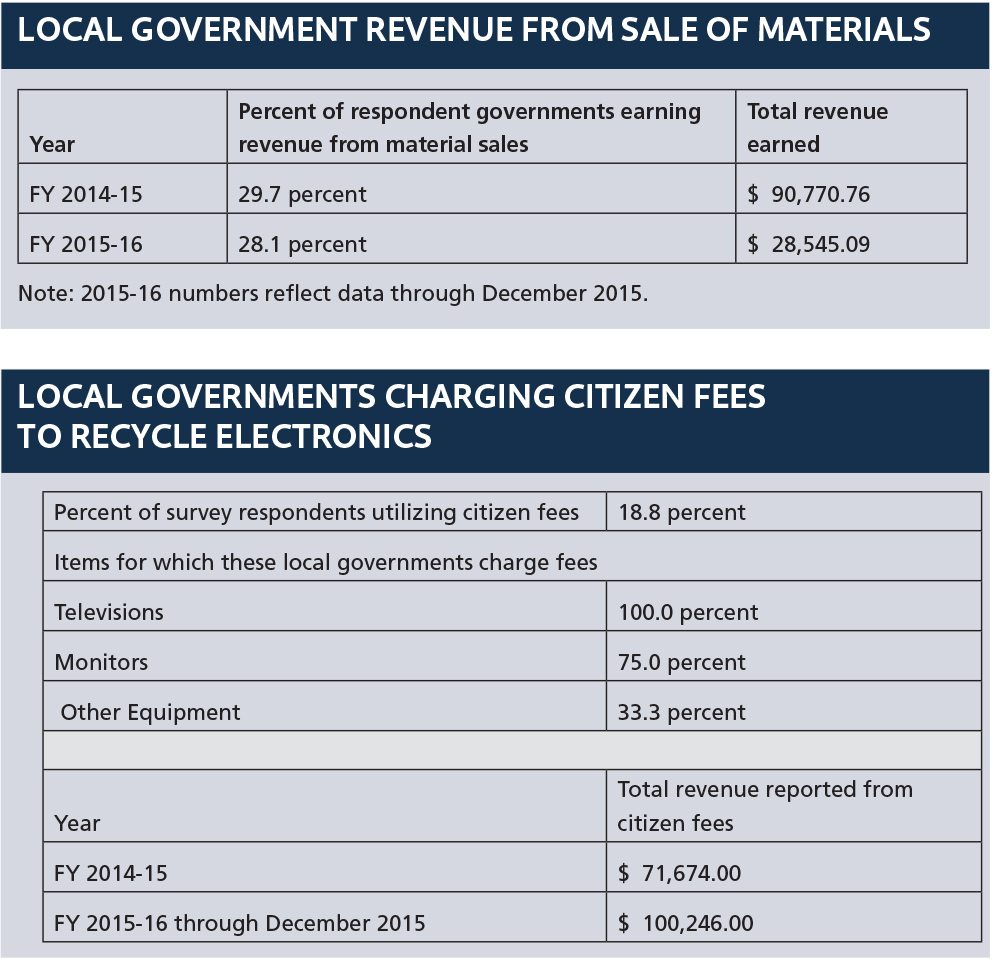

Meanwhile, a minority of communities reported earning revenues from the sale of high-value electronics, and some local governments reported revenue from fees charged directly to citizens for recycling services. The tables below provide an overview of program revenues as reported by survey respondents.

Meanwhile, a minority of communities reported earning revenues from the sale of high-value electronics, and some local governments reported revenue from fees charged directly to citizens for recycling services. The tables below provide an overview of program revenues as reported by survey respondents.

An eye-opening cost increase

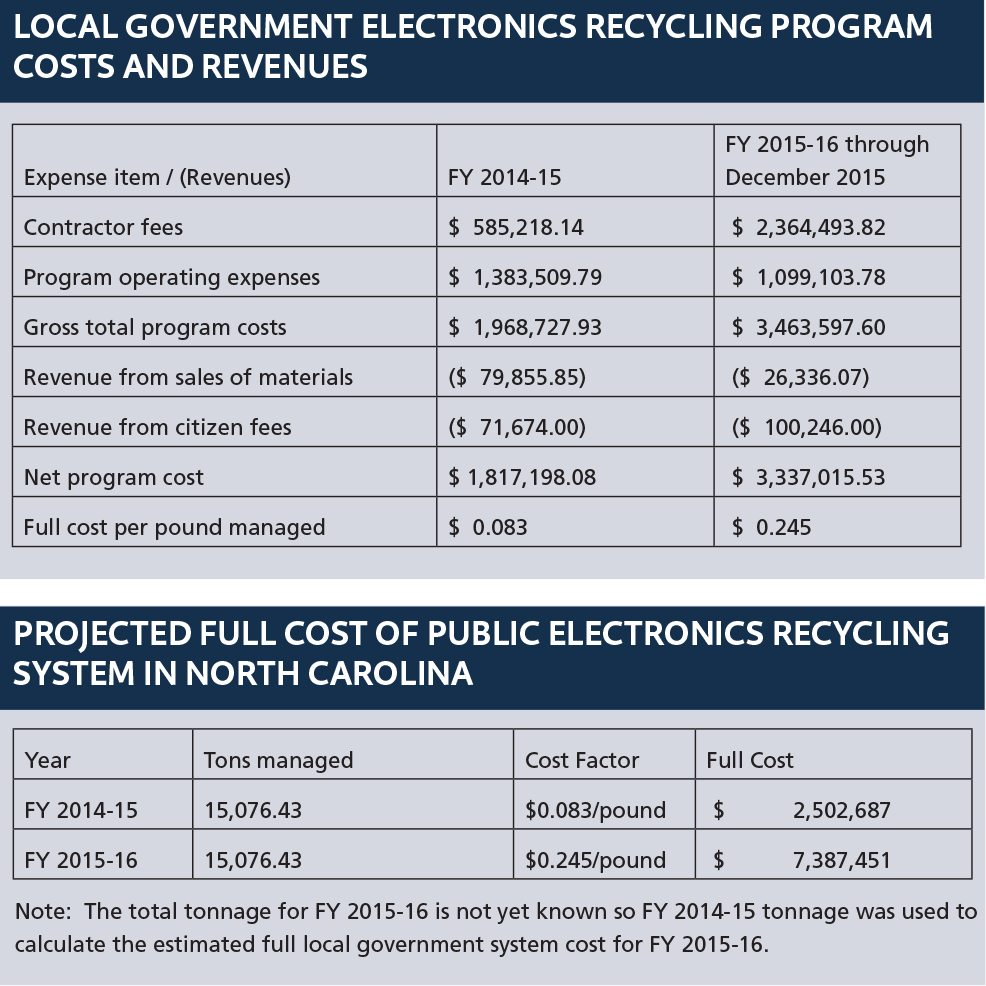

By combining the expenses paid to electronics recycling contractors and the expenses for program operations, it is possible to characterize the full gross cost of the public electronics recycling programs. When revenues from the sale of equipment and citizen fees are taken into account and applied against program expenditures, a picture of the net cost for public electronics recycling programs comes into focus. See the tables below for details.

The full cost per pound for operating local electronics recycling programs in North Carolina during FY 2015-16 increased 295.2 percent over FY 2014-15, and when annualized, survey results reveal a projected system cost of nearly $7.5 million for FY 2015-16, or just under $0.75 for each citizen in North Carolina.

Despite this substantial increase in cost, citizens in North Carolina and beyond continue to turn to their local governments for responsible electronics recycling services. As a result, both local and state decision-makers are being challenged to ensure that public systems are functioning as effectively as possible.

Despite this substantial increase in cost, citizens in North Carolina and beyond continue to turn to their local governments for responsible electronics recycling services. As a result, both local and state decision-makers are being challenged to ensure that public systems are functioning as effectively as possible.

In North Carolina, there is evidence that the producer responsibility components of our law could be strengthened to better share the cost burden amongst the various stakeholders, a step that would deliver relief to local government budgets. Even still, North Carolinians from the Great Smoky Mountains to the Outer Banks have the benefit of widely available public recycling infrastructure to manage old televisions and computer equipment.

Is 75 cents per person per year a reasonable price to pay for responsible recycling of electronic equipment? To put this in perspective, consider it is estimated that local governments in North Carolina spend more than $5 per citizen per year to provide curbside recycling service.

It is hoped that data from the North Carolina survey will help as we continue to consider the costs and benefits of electronics recycling.

Rob Taylor works for the State Recycling Program in the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality. At NC DEQ, he leads a team of staff responsible for providing technical assistance to public recycling programs throughout North Carolina on a wide range of recycling related issues. Taylor also serves on the R2 Technical Advisory Committee, representing public interest and regulatory stakeholders of the R2 standard.