Real Window Creative/Shutterstock

This article appeared in the June 2024 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

As the Republican-majority Iowa Senate neared a final vote on controversial changes to Iowa’s beverage container deposit program, including one allowing most grocery and convenience stores to stop accepting cans and bottles from residents seeking their 5-cent refunds, several in the chamber made clear that only one political party was behind it.

“You’re making it harder to recycle, Sen. Schultz, Senate Republicans,” Joe Bolkcom, a now retired Democratic senator from Iowa City, said at the time, referring to his colleague, Sen. Jason Schultz, who shepherded the bill through its Senate votes. “Congratulations.”

Schultz responded that the bill would help grocers and everyday Iowans — “This bill does everything they want,” he said — and would lead to more standalone redemption centers by giving them a greater share of each nickel deposit. The bill passed the Senate with 29 Republicans and one Democrat in favor, 15 Democrats against.

Around a month later, the Democrat-controlled California State Legislature approved that state’s landmark extended producer responsibility law. The bill would mandate plastic waste reductions and heightened recyclability for packaging and other goods for years to come, and all Republican members either voted for it or were absent.

“It was an effort that came as a result of a long, long negotiation between environmental and business community representatives,” bill author State Sen. Ben Allen, D-Santa Monica, told the local Beverly Press afterward. “It’s an example of people coming together from all sides of the spectrum to help solve a major problem.”

Both examples happened in 2022, and both illustrate the paradoxical politics of recycling in capitols across the country, based on interviews, reports and talks by dozens of advocates, legislators, researchers and others in recent weeks. Call it Schrodinger’s recycling: simultaneously partisan yet bipartisan, divisive yet safe, widely popular yet plainly tied to a state’s political leanings.

“You can talk about recycling and you know you’re not going to get a pitchfork in the back,” said Billy Johnson, chief lobbyist at the Recycled Materials Association, which recently changed its name from Institute of Scrap Recycling Industries.

Johnson pointed to notable, recycling-focused odd couples in Congress, such as New Jersey Democrat Rep. Frank Pallone and Illinois Republican Rep. John Shimkus in the House or Republican Sen. John Boozman of Arkansas and Democrat Sen. Tom Carper of Delaware, who co-chair the Senate Recycling Caucus.

“They’ll disagree on 99% of everything else but recycling,” Johnson said. On that, “it’s difficult sometimes to see the light between them.”

Finding shared cause across party lines helped lead to the inclusion of tens of millions of dollars for recycling education and infrastructure grants in the 2021 Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which passed with mostly — though not only — Democrat support.

On the other hand, there are conspicuous cracks in this bipartisan image. Boozman and Carper’s proposals to enhance federal recycling and composting data and provide more grants, particularly to underserved areas, keep passing the narrowly Democratic Senate but have yet to find a foothold in the narrowly Republican House, for example.

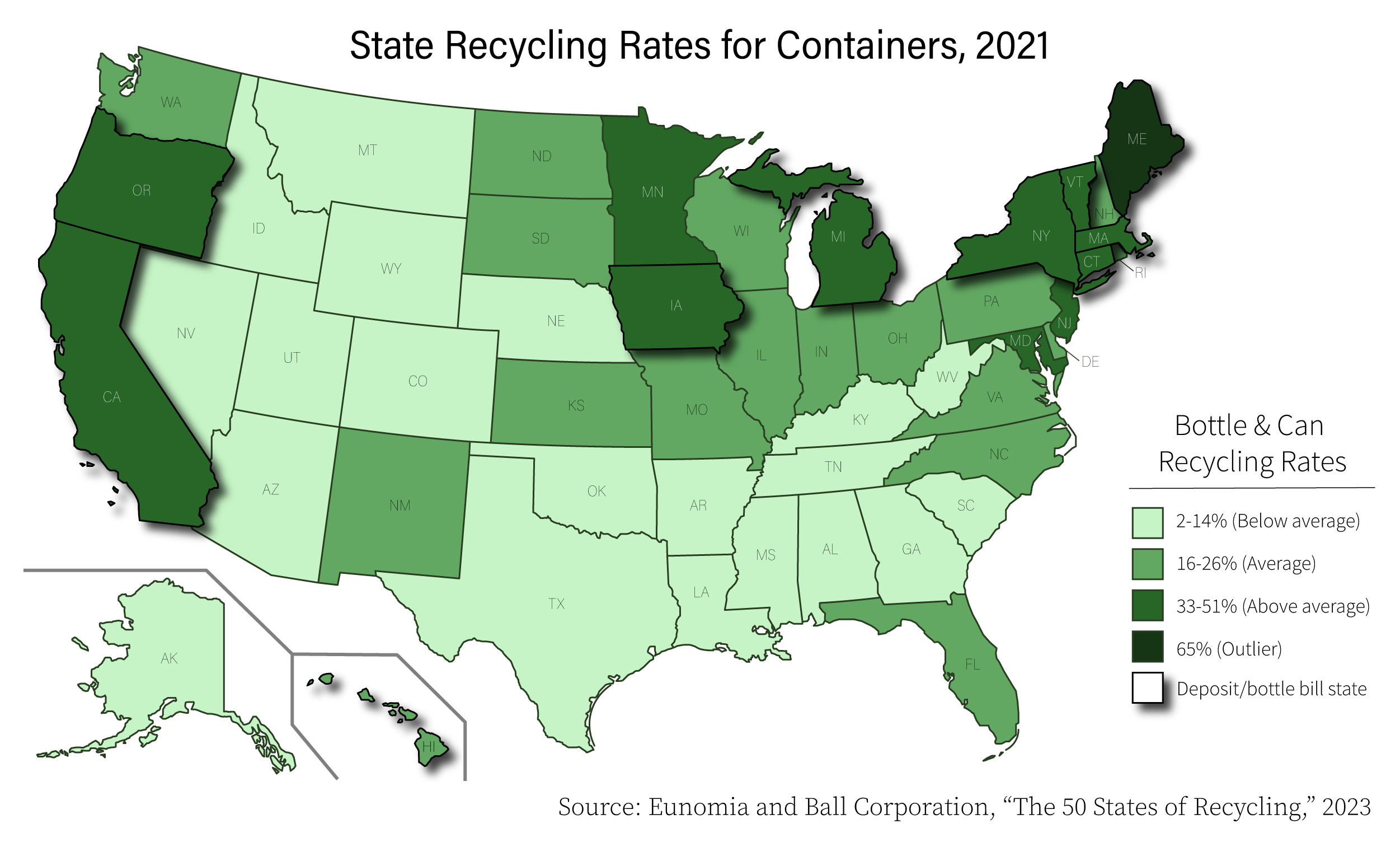

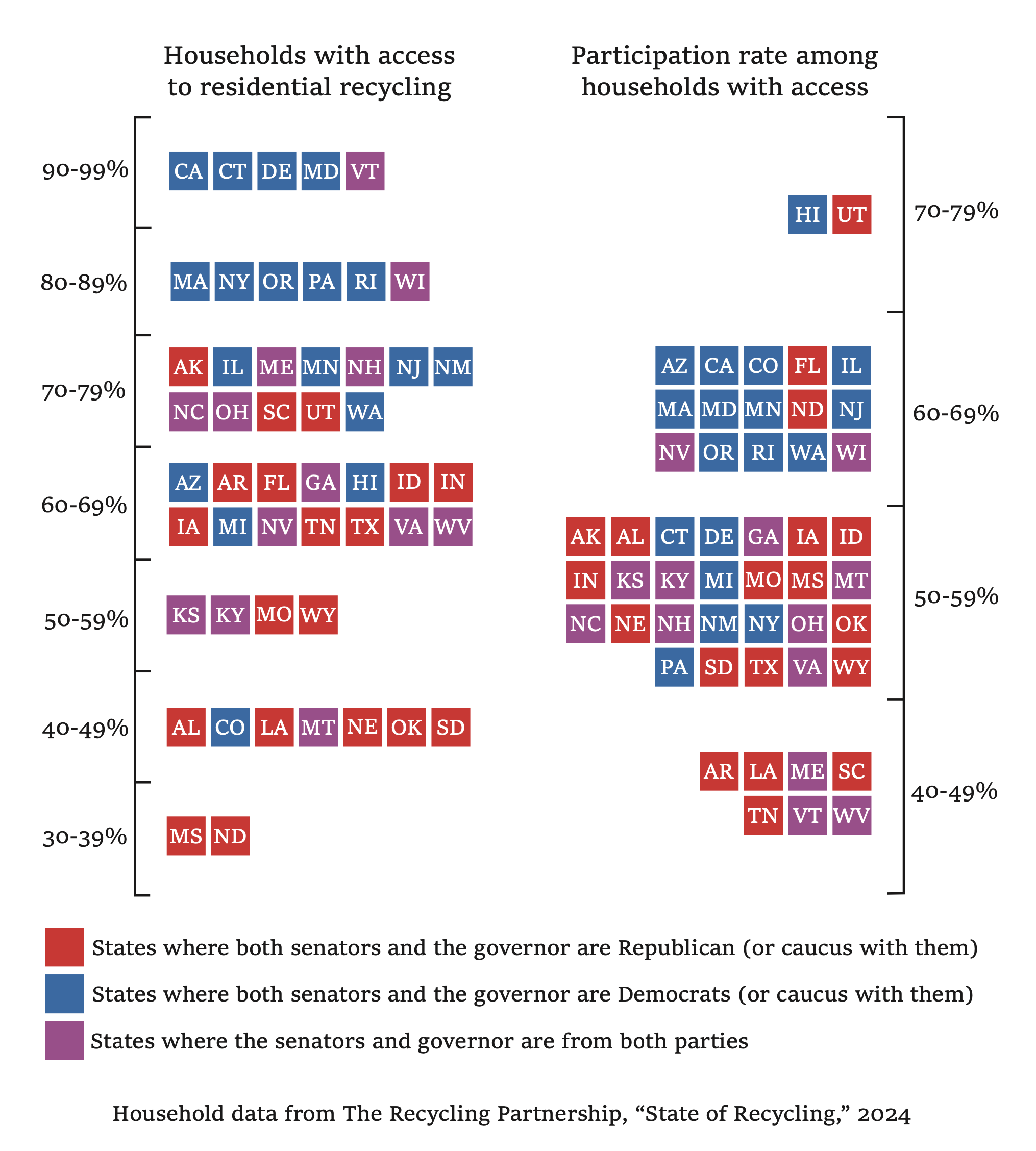

Looking at the party affiliations of governors and U.S. Senators as a proxy for each state’s political makeup, blue states on average recycle more than twice as many of their cans and bottles as red states, based on the December 2023 50 States of Recycling report from Ball Corporation and Eunomia. Among 10 bottle-bill states, all but Iowa are blue or mixed.

Each of the four states with paper and packaging EPR programs at the start of 2024 were blue or mixed when sorted by the same metric; the Minnesota House’s vote to become the fifth EPR state on May 17 was entirely party-line, with Democrats in favor.

“A lot of the mandatory recycling laws that were passed when I was in high school — so that was 30-plus years ago — a lot of those passed with bipartisan support, but it was a total different universe,” said Dylan de Thomas, vice president of public policy and government affairs at The Recycling Partnership, which has zeroed in on EPR laws as the most impactful way to increase recycling rates. “We just are not in that space anymore.”

De Thomas emphasized that he speaks with legislators of all stripes, no demographic is a monolith, and members of both parties can and do care about recycling as an economic and environmental issue. But today’s polarization and us-versus-them thinking can push bipartisanship aside even when people agree deep down, he said. “It’s not about the policies, it’s about the politics.”

Patterns of difference

Several recent studies and surveys shed light on possible sources for the political gulf in recycling.

Part of the difference is likely everyday politics: Using government to encourage recycling often entails spending and regulation, both of which conservatives tend to resist in some contexts. More right-leaning survey respondents to a 2019 Axios poll were half as willing as their more liberal peers to pay higher taxes to support recycling programs, for example.

Social psychology can also play a role. The feeling that recycling is something that people like you do — or don’t do — could in turn affect how readily you categorize trash as recyclable, a 2020 study in the Journal of Environmental Psychology suggested. An earlier study that analyzed national surveys of recycling behavior found Democrats were more likely to say they recycle most of the time, which the authors attributed to a rise in “lifestyle politics,” or using choices as statements of personal values.

Whatever the reasons, the correlation between politics and recycling behavior and policy seems clear, with higher access to programs and participation in bluer states, broadly speaking, based on data from the Eunomia report and TRP’s 2024 State of Recycling.

In Minnesota, the Senate Republican Caucus said the “hyper-partisan” new EPR law would raise costs for employers and customers.

“Unfortunately, instead of finding balance, Democrats are forcing through controversial environmental restrictions that will crush Minnesotans with more price increases on top of inflation and $10 billion in new taxes passed last year,” Sen. Justin Eichorn, the party’s lead on the Environment, Natural Resources, and Legacy Committee, said in a written statement.

Democratic supporters, meanwhile, hailed the law as an incentive for industry to recycle more.

“Across Minnesota, we are inundated with packaging, from our doorsteps to store shelves,” Rep. Sydney Jordan, Vice Chair of the House’s Environment and Natural Resources Finance and Policy Committee, said in a written statement. “Today’s bill takes steps to ensure the producers of this waste are paying their fair share.”

Political dynamics can play out across states and regions. Mark Dancy, president and founder of WasteZero, a waste-reduction consulting business out of South Carolina, said WasteZero does much of its work further north because of its home region’s low landfill costs, political polarization around the topic and a general lack of interest.

Political dynamics can play out across states and regions. Mark Dancy, president and founder of WasteZero, a waste-reduction consulting business out of South Carolina, said WasteZero does much of its work further north because of its home region’s low landfill costs, political polarization around the topic and a general lack of interest.

“Our company doesn’t spend a lot of time in the South,” he said during a session at the Waste Expo conference in Las Vegas in May. The circular economy is likely to grow in the coming decades, he added, “but there are parts of the country that are still going to be way behind.”

There are exceptions to the pattern. Rural and conservative Alaska cracks the top 15 in the proportion of households with access to residential recycling service, according to the TRP report, while blue Colorado comes in 45th. Republican Florida and Utah are near the top of the pack with a participation rate of around 70% among the same households, almost double that of purple Vermont and West Virginia.

“We’ll see in Florida, a lot of times the economics drive activity you might not see elsewhere,” such as productive end markets for construction and demolition materials, said Jim Marcinko, southern tier recycling director at WM, at Waste Expo. “We do more C&D in Florida than anywhere else in the country.”

Another paradox complicates the pattern as well, several business leaders said: As a state’s interest in and support for recycling rises, so do the regulatory obstacles, and vice versa. Mick Barry, former president of Mid America Recycling in Iowa and past chairman of the National Recycling Coalition, described it as, “One discourages doing anything, the other needs to be encouraged.”

California, for instance, requires extensive recycling of containers, organics and C&D materials. But building a facility to accomplish those goals takes years of jumping through the hoops of stringent environmental impact rules and other regulations, said Richard Ludt, director of environmental affairs at Interior Removal Specialist Inc., a C&D company in the Los Angeles area.

“In Ohio, I could damn near permit a facility like this over the counter,” he quipped. “The bureaucracy kills us.”

At the other end of the spectrum, Rody Taylor said the C&D business he opened last year, KC Dumpster Company, was Missouri’s first of its kind, and state regulators knew next to nothing about his work. He struggles to compete with cheap landfill fees, he told a Waste Expo audience, but he’s also the only game in town.

KC Dumpster benefits when big developers like Facebook carry “West Coast policies” for C&D diversion into their local projects, Taylor said, and he’s also working on Recycling Certification Institute approval — all of which brings more rules for him to follow. But they’re coming from private entities rather than government agencies, which he prefers.

“There’s just a whole lot to overcome in my case, and the fact that I’ve got my feet on the ground is something I’m pretty proud of,” Taylor said. He added with a laugh, “I’d hate to live in California.”

Recycling regulations aren’t automatically a drag, noted Ludt, a past advisory board member for the Solid Waste Association of North America.

“My business model wouldn’t work in any other state,” he said, and he called the recycling industry “notoriously bad at self-policing.” In fact, more regulation could help ensure that diverted materials go where they’re meant to go and companies don’t inflate their numbers. And he said pushing for sustainability is the right thing to do.

“We absolutely have to protect the environment, because it’s the only one we’ve got,” Ludt said. As long as they don’t price supportive companies out of business, “regulations can be phenomenal.”

The case of Iowa

Recycling’s many political contradictions converge on the Hawkeye State. Its bottle bill came in 1978 at the hands of Republican Gov. Robert D. Ray and then-State Rep. Terry Branstad, both icons of the state’s Republican Party, chiefly as a litter-control tool, said Barry, formerly of Mid America.

“The bottle bill created an ethic in every Iowan from, I’m almost 74 now, to my little grandkids that I babysit,” he said. Barry called the bill a cornerstone of the state’s recycling system and the primary reason that Iowa’s bottle and can recycling rate is four times as high as neighboring Nebraska’s, by Ball Corporation’s count.

The program carried on, broadly popular and unchanged, until proposals to repeal it or alter it started cropping up over the past decade or so, said R.G. Schwarm, executive director of a nonprofit association of recycling businesses called Cleaner Iowa. The group was created to educate legislators about the bottle bill’s benefits as a result.

“We appreciate that the bottle bill is a free market system that hasn’t required a penny of government money,” Schwarm said. “After 40 years, some changes were needed, and we wanted to make sure that when these changes were implemented, the consumer was also included.”

Proposed changes included expanding the bottle bill to include more containers, such as water bottles, or directing unredeemed deposits into a state fund rather than letting the producers keep them. What carried the day in 2022 was a package of proposals that in part increased redemption centers’ handling fee, or share of the nickel deposit, from 1 cent to 3 cents, which was lauded across the board as necessary to support existing centers and encourage new ones. Kevin Kinney, the former state senator who was the only Democrat voting for the changes, said in an interview that he voted yes to support a struggling center, and its jobs, in his district.

The bill also exempted hundreds of grocery and convenience stores from having to take back cans and bottles, citing sanitation and food safety concerns. Though Schwarm said the provision had support in both parties, it became the center of a partisan dispute. In the state Senate, Democrats argued Iowans should be able to redeem containers where they bought them and participating would become more difficult, while Republicans argued the higher handling fee, plus a provision allowing mobile redemption centers, would make up the difference in redemption locations.

Two years on, a recent survey by Cleaner Iowa found more than 2,000 stores had stopped accepting containers, including several that weren’t exempt from participating even under the 2022 changes, while redemption centers increased to about 100.

Democrat State Sen. Bill Dotzler, who in 2022 called the changes “the first step of just totally eliminating the bottle bill,” said his views hadn’t changed since.

“It’s going to be a slow death in my view,” he said in May, pointing to the 29 counties Cleaner Iowa found have no redemption centers. “This is kind of a pseudo bottle bill. In rural Iowa, it’s going to be pretty much nonexistent.”

Republican State Rep. Brian Lohse, who has popped up in local media saying the bottle bill might need to be repealed because of its struggles, said in an interview that repeal would be a last resort. He still supports the store exemptions — “These things should not be in those environments” — but conceded shortcomings in 2022’s legislation.

“It’s just not working like we had hoped, or at least like I hoped,” he said, adding the state needs to enforce the new rules.

The Legislature plans to review the changes starting in 2025, and potential tweaks are already up for discussion. Schwarm still argues that places that sell bottles and cans should take them back, and some Republicans introduced bills this year undoing some of the exemptions. Dotzler suggested adding water bottles as redeemable containers, and Lohse said he’s interested in steering unredeemed deposits toward curbside recycling for all households.

Above all, support for the program is widespread, with more than 80% of Iowans in favor, according to Cleaner Iowa polls, and the state boasts one of the highest recycling rates in the country. Dotzler, Kinney, Lohse and another legislative Republican who’s worked on the issue, State Sen. Ken Rozenboom, all said they took part in the redemption program.

“This really is a conversation that I think everyone can have because they’re materials that we all interact with,” said Jane Wilch, recycling coordinator for Iowa City and president of the Iowa Recycling Association. “We really approach them as relatable topics to everyone, no matter the party, no matter where anyone stands politically.”

The power of the nickel deposit gets some of the credit, Barry added.

“For the general public, the bottle bill puts a value on a raw material. That’s education,” he said. “We’re not educating anyone anymore, we’ve got nothing but turmoil in the bill, but people want it.”

Common ground

Common ground

Researchers at Idaho State University a decade ago found that the framing of the recycling issue affected how people perceived it, particularly if they were more conservative.

The researchers compared responses to two main ways of describing why recycling matters: a duty-based framing that emphasized responsibility, efficiency and dwindling space in landfills, for example, and a civic engagement-based framing that emphasized natural resource and energy savings, impact on the climate and blaming greedy corporations.

Overall, more liberal respondents tended to agree with the value of recycling regardless of the framing, the study found. More conservative respondents typically voiced agreement with the duty-based explanation.

In other words, in the buffet of reasons to want to recycle, liberal people tend to find a wider variety of the dishes appetizing — but everyone can find something to eat.

“That’s one reason I have worked in recycling for nearly 20 years — there is someone for everyone to like,” said Kate Bailey, chief policy officer at the Association of Plastic Recyclers, which owns the publisher of this magazine and supports EPR, mandated recycled content and similar policies. Parties disagree on the proper role of government in the details, Bailey added, but “good policy is about compromise — no one gets everything they want, but everyone is heard and can help shape a workable solution.”

Real-life examples of the Idaho study’s findings have popped up in recent months, as concerns over full or hazardous landfills have prompted calls for better recycling plans both on conservative Long Island and in liberal L.A. County.

In northwest Arkansas, a medium-sized but booming region that’s home to Walmart and other corporate headquarters, neighbors of the region’s primary landfill have been fighting the WM-owned facility’s attempts to expand as its remaining capacity dwindles.

The area’s Republican representatives in the state House, Robin Lundstrum and Steve Unger, have called for air and groundwater testing and the landfill’s potential closure, and they’ve voiced support for gasification, a form of processing MSW en masse into fuel and other usable materials. Unger said the issue stuck with him as he began driving past the landfill to visit a relative and was struck by its finite capacity.

“I think we should all be environmentalists,” he said. “I am a conservative, but I believe in clean water, I believe in clean air.”

Similarly, advocates from Florida to Oregon said the economics of recycling – jobs created, materials put to work, businesses opened – is a skeleton key to unlocking support from across the ideological spectrum.

“That’s the manna from heaven that all politicians want to see,” said de Thomas with TRP, who added that successful policy requires engaging with the full variety of communities, businesses and other stakeholders affected. “Not one stakeholder can plant the seed and till the soil themselves.”

A bipartisan group in Congress has introduced a bill to remove the excise tax on large trucks, which would benefit many industries, as Jim Riley, the National Waste & Recycling Association interim president and CEO, noted during Waste Expo. More narrowly, a national deposit program is getting some traction, too.

“We are on the cusp of getting a national recycling refund introduced to Congress in a bipartisan way,” said Heidi Sanborn, founding director of the National Stewardship Action Council, echoing a similar sentiment from Barry. “I’m very, very hopeful because there’s so much industry hunger for this material.”

In the end, the heart of recycling’s bipartisan appeal seems clear when people of different backgrounds and politics are asked not which policy they favor or which party they belong to but instead simply why they recycle.

“One thing that really resonates with me personally is I kind of hate the idea of using something for a really short finite time and it existing forever in the world,” said Nick Lapis, director of advocacy for Californians Against Waste and a strong proponent of the state’s industry regulation. Lundstrum, one of the Arkansas Republicans, put it this way: “I hate throwing away something that I know can be reused.”

Editor’s note: This article has been updated to clarify Richard Ludt’s previous role with the Solid Waste Association of North America.

Common ground

Common ground

Experiences on the ground

Experiences on the ground

Transparency is a powerful tool

Transparency is a powerful tool