Cytonn Photography/Unsplash

This article appeared in the August 2024 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

Through partnerships and collaborations, the plastics industry has the opportunity to amplify individual efforts and contributions, pool resources, leverage diverse expertise, channel creativity and drive innovation. All of these are critically important when looking to solve a complex issue such as mismanaged plastic waste and building a circular economy for plastic materials.

For many years, my career at Nova Chemicals has revolved around being a connector to create change, connecting through industry associations, coalitions, consortiums, initiatives, investments, with our customers and their customers, with nonprofits and with governments. I’ve seen firsthand that partnerships and collaborations can help accelerate progress by leveraging expertise and catalyzing investments and innovations to find solutions through private and private/public models. There are three ways partnerships and collaborations can make a difference: investing in recycling infrastructure, encouraging innovation and circular design, and impacting public policy.

Driving Investment

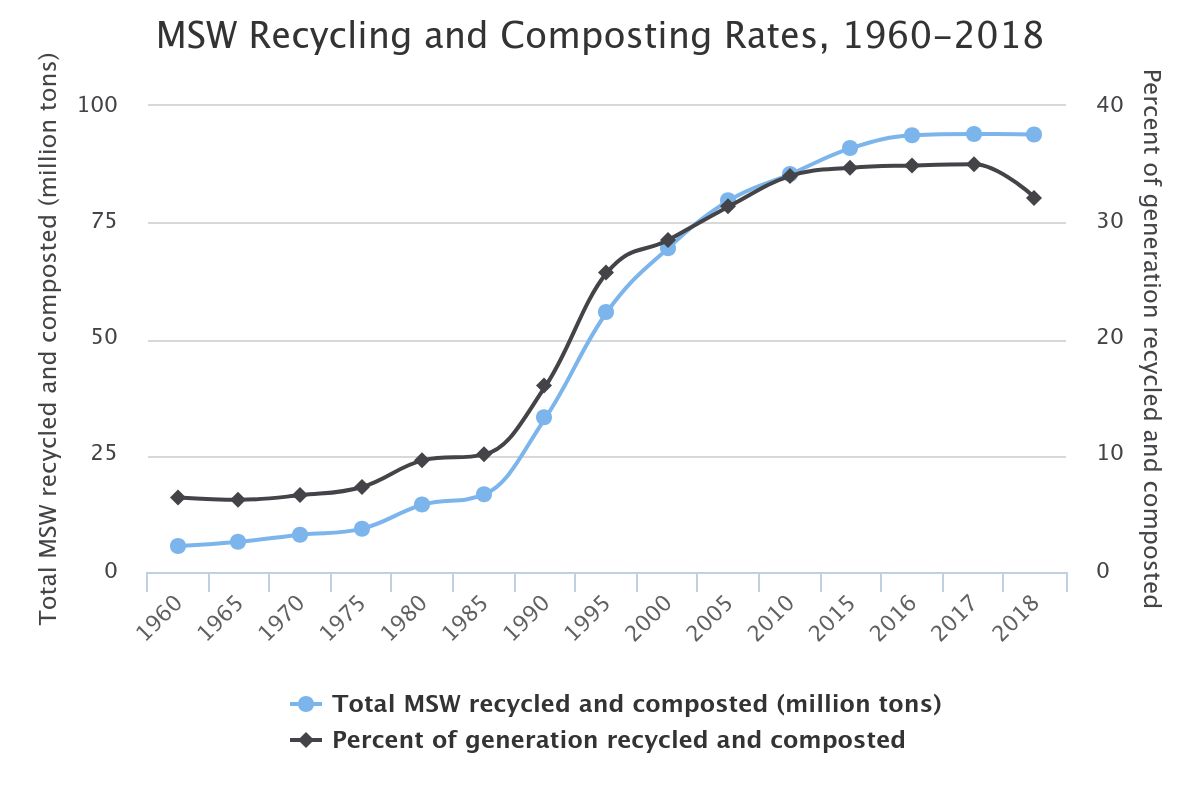

According to The Recycling Partnership, the U.S. alone needs $17 billion investment over five years to deliver the full benefits of recycling to the public, and the estimated return on that investment could be $20 billion over 10 years. Collective investment is an excellent way to deploy catalytic financing into sustainable technologies.

One investment collaboration is the Closed Loop Circular Plastics Fund within Closed Loop Partners’ Infrastructure Group. Established in 2021 by Nova Chemicals, LyondellBasell and Dow with Closed Loop Partners, the fund’s mission is to advance the recovery and recycling of polyethylene and polypropylene in the U.S. and Canada to meet growing demand for high-quality, recycled content in products and packaging from consumer brands. The strategy seeks to deploy $55 million and to recycle over 500 million pounds of plastic over the fund’s lifespan.

Since its launch, the strategy has made several catalytic debt and equity investments to both private companies and public organizations, financing post-pilot scale projects that advance collection infrastructure, sortation capabilities, enabling technologies and re-manufacturing of PE and PP. One investment has been in Greyparrot, a leading artificial intelligence waste analytics platform that improves transparency and automation for plastics sortation in recycling facilities. Supported by funding, Greyparrot has grown to now identify over 25 billion waste objects each year, with 100-plus of its Greyparrot Analyzer Units spread across 20 countries, and is working with three of the top eight global waste management companies to improve recycling efficiency and increase resource recovery.

There are several other investment funds focusing on eliminating plastic waste and building a plastic circular economy, including Infinity Recycling, Circulate Capital and The Alliance to End Plastic Waste and Lombard Odier Investment Managers’ circular plastic fund. Recently the U.S. State Department announced the launch of the End Plastic Pollution International Collaborative, an international public-private partnership created to catalyze governments, NGOs and businesses to support innovative solutions to the plastic pollution crisis. All of these are great examples of how we can work together to invest in solutions.

Inspiring Innovation and Circular Design

Designing for circularity has benefited greatly from cross-sector collaborations. The Association of Plastic Recyclers developed the APR Design Guide, a comprehensive design guidance and testing protocol that measure package design against industry-accepted criteria. And the Canada Plastic Pact led a collaborative effort to develop the Golden Design Rules, a guidance and standards framework for Canadian companies to adjust their plastic packaging designs and contribute to a circular plastics economy. Harmonized approaches like these strive to provide alignment and a common framework, ensuring consistency, reducing confusion and improving widespread acceptance while still allowing for flexibility, creativity and innovation.

Recently in Canada, Nova Chemicals launched a Centre of Excellence for Plastics Circularity, a hub for knowledge exchange and technology development for plastics circularity through a new network of industry peers and research institutions. The first call for expression of interest received nearly 50 proposal submissions from Canadian universities and research organizations.

Sharing progress is essential in building momentum and showcasing the innovative solutions that are underway. According to the Global Partners for Plastics Circularity, there are 116 recycling infrastructure projects planned, operational or under construction representing a $18 billion financial investment that plastic makers and the plastics value chain are making around the globe to create a more circular future. The Alliance to End Plastic Waste participated in the fourth session of the United Nations’ Intergovernmental

Negotiating Committee in Ottawa in May, hosting a Solutions Fair that showcased over 40 different solutions to make change and create a plastics circular economy. All happening now. All over the world. And they created a short video to highlight this circularity in action.

Partnerships to Impact Policy

Cross-sector partnerships also can play a crucial role in driving effective policy. Industry and trade associations, coalitions and initiatives can bridge gaps, foster dialogue and enable collective decision-making that finds creative solutions and shared goals by leveraging diverse knowledge and expertise. This can result in sustainable change at scale.

Guiding principles and model legislation are some of the ways these groups can help influence policy decisions and solutions that can transform post-consumer plastics into an ongoing resource. America’s plastic makers have proposed a national and comprehensive strategy toward a plastics circular economy, Five Actions for Sustainable Change, which highlights five critical public policies and actions that can help us achieve success. Innovations and new end market developments are other ways collaborations can stimulate business economics and create the necessary supply and demand for used plastics.

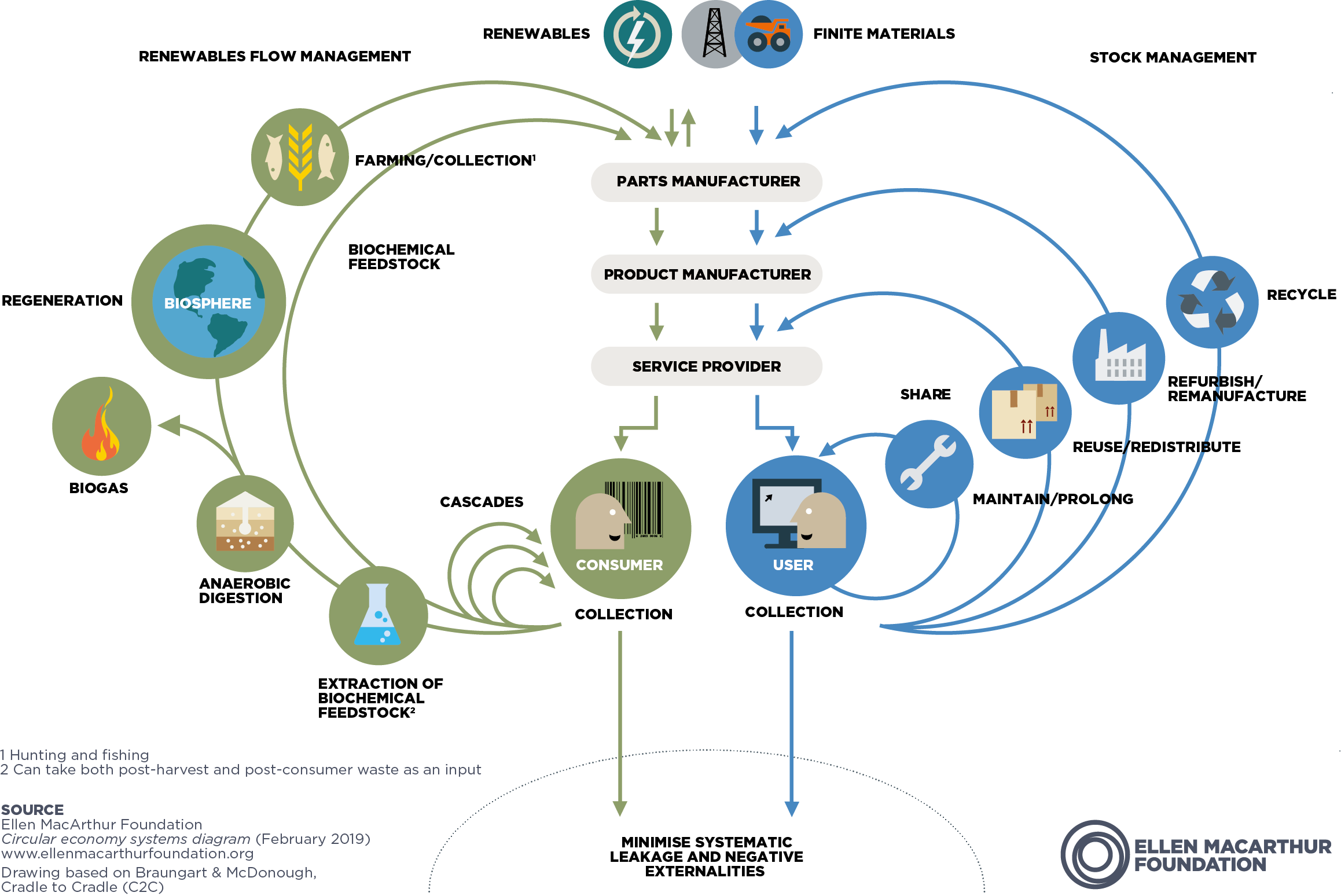

If you want to read more, there are several other long-term roadmaps and frameworks to take us from a linear take-make-waste/dispose economy towards a circular economy for plastics:

- America’s Plastic Makers developed a Roadmap to Reuse.

- The Ellen MacArthur Foundation Plastic Pacts Network has a common vision with localized targets.

- The Recycling Partnership’s 2024 State of Recycling Report shows what will have the largest impact.

- The Alliance to End Plastic Waste partnered with Roland Berger on The Plastic Waste Management Framework, offering insights into policies and levers that can be adopted to improve plastics circularity.

What do all of these have in common? They each show the complexity of the situation and the interconnectivity of the players, policies, innovations, infrastructure and supply-demand balance needed to make it all work. There are actions that individual entities can take to move the needle, but at the very heart of the solution is a need for partnerships and collaborations to accomplish this overwhelming but achievable task.

There are many ways partnerships and collaborations are helping us to get closer to a future with zero plastic waste. In my experience, the greatest ideas start with simple conversations. I am excited for the future because I see firsthand that there is a focus, intensity and passion that drives us all towards a common deliverable. It will take time, but I am confident that this collective impact will create lasting change.

Julianne Trichtinger is manager of industry affairs within the government relations team at Nova Chemicals. She works closely with key industry associations and strategic partnerships as an advisor to senior executives and is responsible for monitoring and providing insights into public policy, advocacy priorities and key activities that impact our business and industry, particularly as it relates to a plastics circular economy.

The views and opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not imply endorsement by Resource Recycling, Inc. If you have a subject you wish to cover in an op-ed, please send a short proposal to [email protected] for consideration.

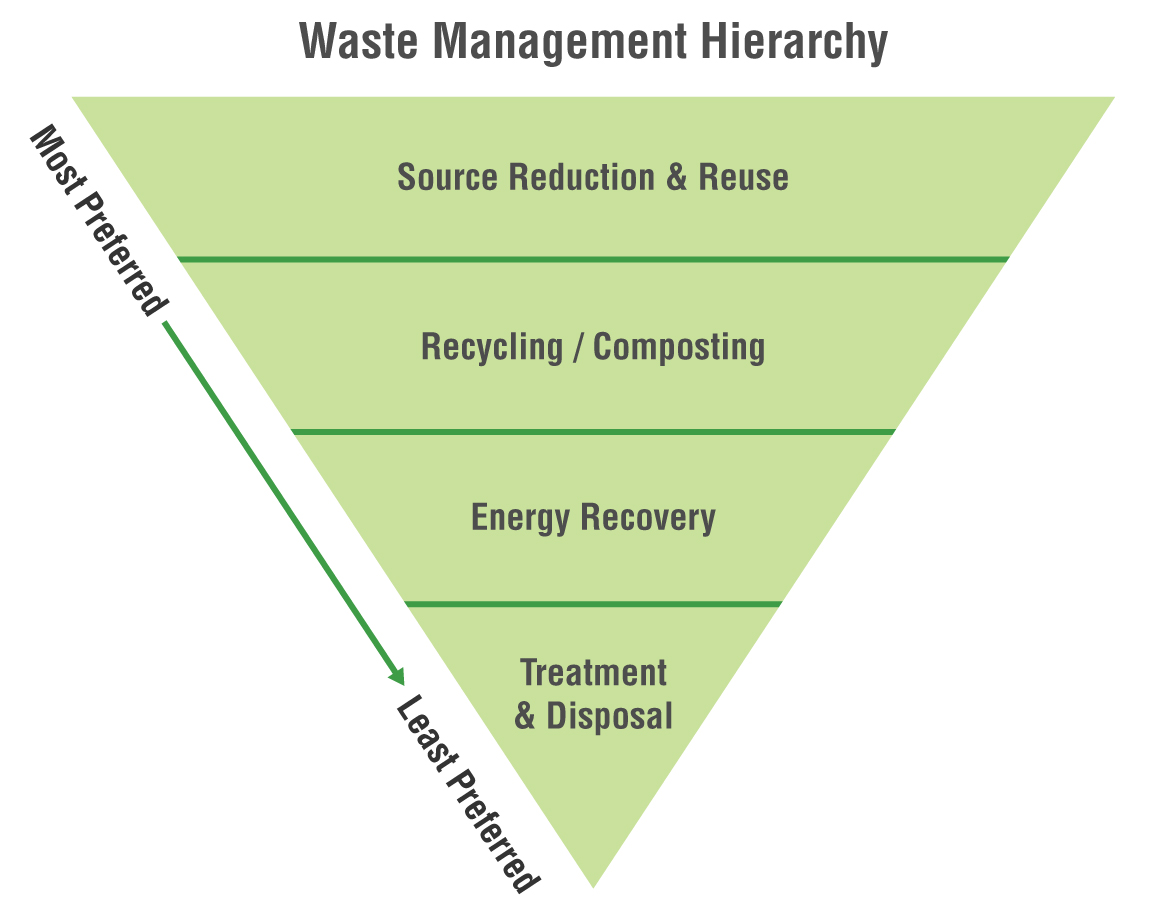

Now, like the hierarchy, it’s time to question circularity before it becomes a hollow simplification that leads us to further inaction in the face of environmental crises. How exactly does this idealized view allow us to grapple with the physical nature of packaging and its rapid pace of innovation? How does it address, plan for and recognize the actual physical barriers for package capture from waste generation to MRF, loss in yield after capture from MRF to secondary processor to end market, and the inherent costs for providing enough of the stuff needed to fully cycle a package back to its original intended use?

Now, like the hierarchy, it’s time to question circularity before it becomes a hollow simplification that leads us to further inaction in the face of environmental crises. How exactly does this idealized view allow us to grapple with the physical nature of packaging and its rapid pace of innovation? How does it address, plan for and recognize the actual physical barriers for package capture from waste generation to MRF, loss in yield after capture from MRF to secondary processor to end market, and the inherent costs for providing enough of the stuff needed to fully cycle a package back to its original intended use?

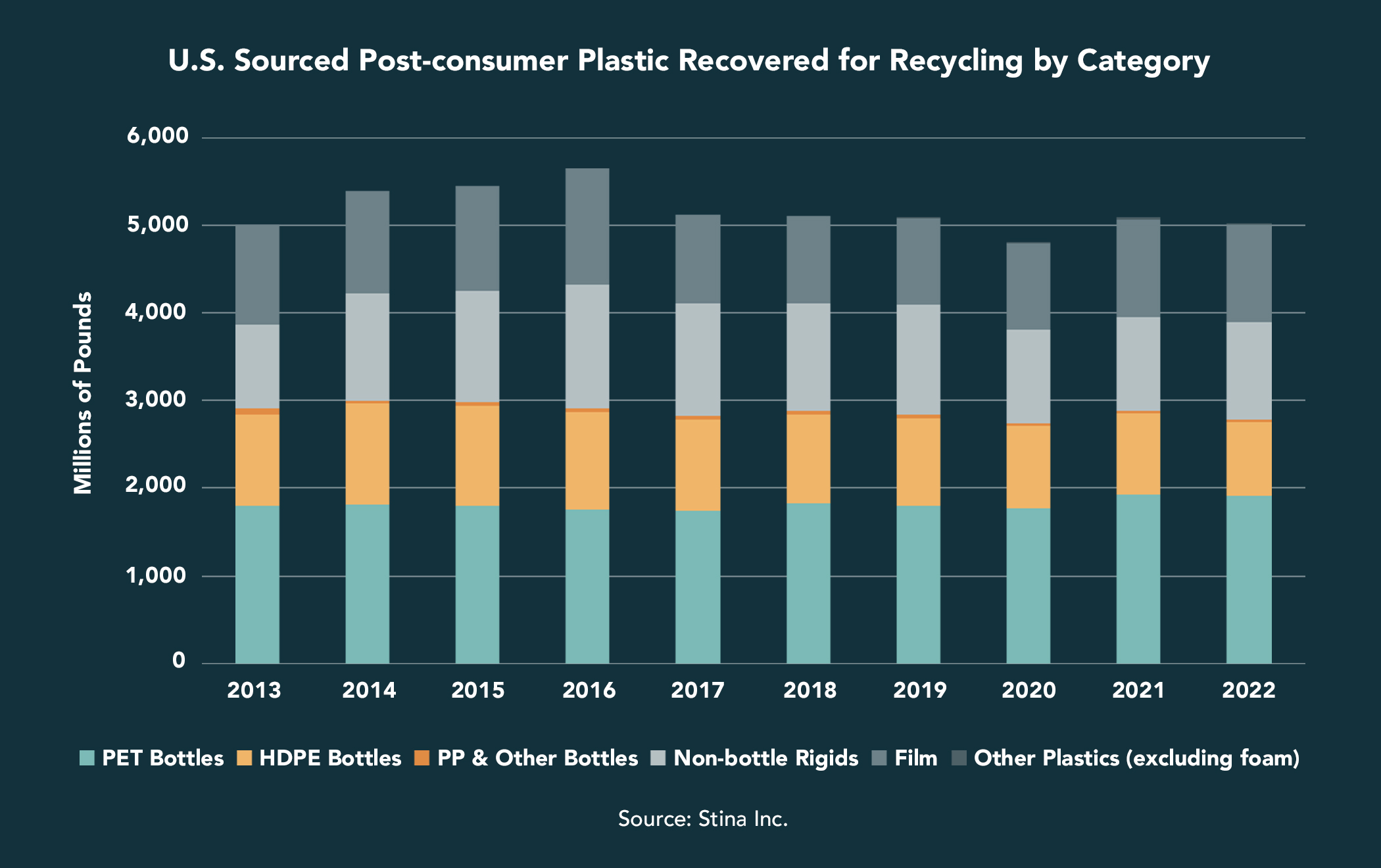

Material trends converge, plateauing growth

Material trends converge, plateauing growth

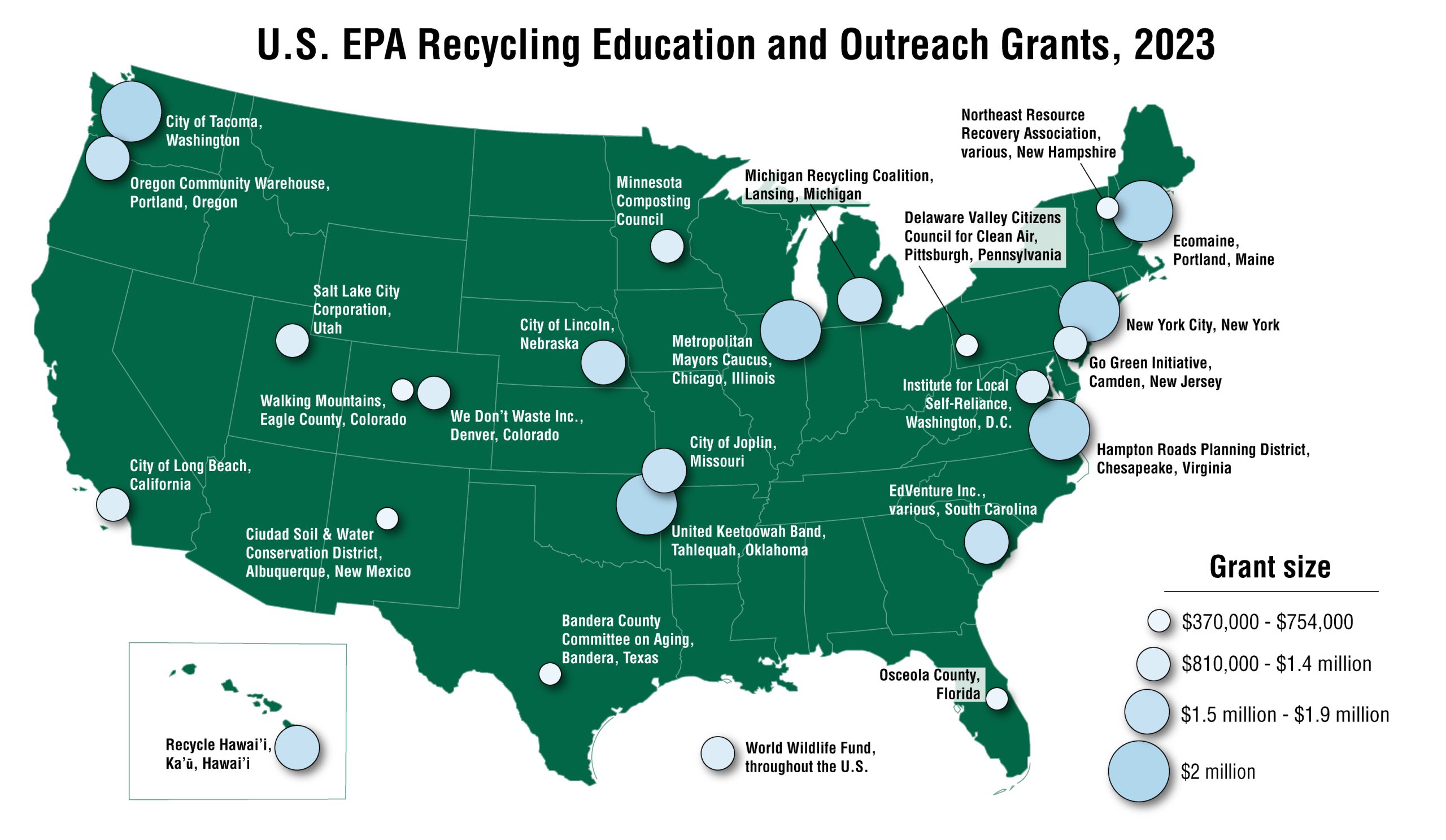

A widespread need

A widespread need