This article appeared in the April 2022 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

This article appeared in the April 2022 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

Recycling decision-making in the U.S. is generally thought to be handled at the local level. For the most part, municipalities decide whether to offer recycling or require private service providers to do so. These municipal systems depend on factors such as resident expectations, local sustainability goals, and, of course, costs.

However, it’s also true that the regions of the country that do the best job of recycling have state-level policy in place that strongly encourages (or outright requires) that recycling be provided. The same is true globally.

As stakeholders look to increase recycling, it is becoming increasingly clear that policy needs to be a core strategy. And as the industry debates policy options, one key factor to consider is whether policy levers will increase or reduce the costs to local governments and their residents.

Dependent on community resources

Recycling policy in the U.S. comes in many shapes and sizes.

States and local governments have utilized disposal bans, mandatory recycling requirements and other policy tools to support recycling program implementation. These types of initiatives have placed the responsibility for providing and/or funding recycling programs on local governments and the taxpayers/ratepayers who use the system. While many states have grant programs, and organizations like The Recycling Partnership have provided funding for local governments to implement best practices, those funds typically don’t provide enough support to cover ongoing, day-to-day recycling operations.

As a result, the availability of recycling and the quality of local programs has depended largely on community resources as well as the commitment of residents and leaders to make the funding of recycling a priority. While many communities have done the bare minimum in terms of material diversion, some have invested heavily in the development of recycling programs and infrastructure, either directly or through contracted service providers. They have purchased trucks, built MRFs, and educated residents on what and how to recycle.

But despite the impressive work of many communities around the country, a growing number of stakeholders now recognize that policy is needed to improve recycling in the U.S., especially as markets have shifted in the wake of China’s National Sword and pressure on brands has spawned major recycling-related commitments.

The result has been a significant amount of focus on policy proposals that move the funding conversation well outside the local sphere.

Spotlight on deposits

One area of discussion has been container deposits.

Beverage container deposits (or bottle bills) have shown they can achieve beverage container recycling rates of 65% to 90%, compared with numbers around 30% in non-deposit states.

Most bottle bills actually pre-date the proliferation of curbside recycling programs, so their impact on municipal efforts and infrastructure was not considered when they were developed. Recently, however, bottle bill debates have centered around the impact that they’ll have on municipal recycling costs and MRF operations.

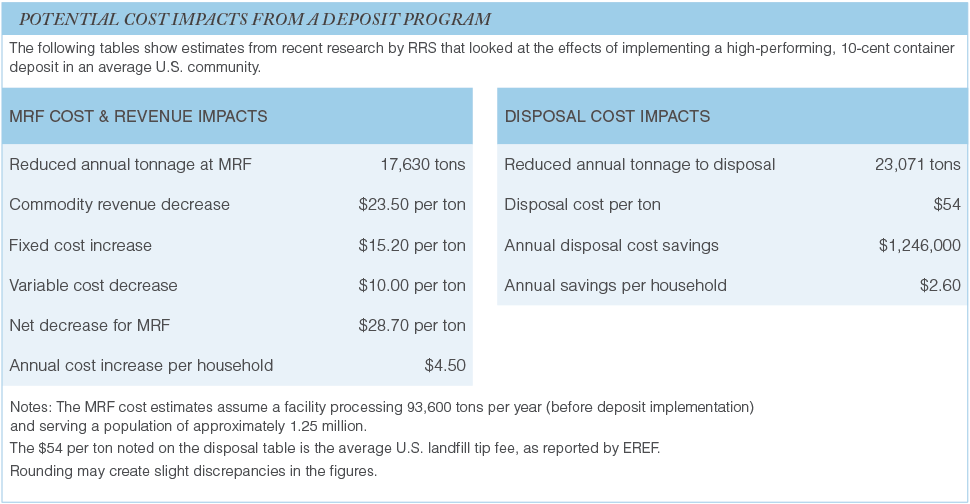

In a recent study for the National Waste and Recycling Association (“Economic Impact of Beverage Container Deposits on Municipal Recycling Processing Costs”), RRS analyzed the impact of beverage container deposits on the costs and revenues of a typical MRF in the U.S. (a facility processing 93,600 tons per year and serving a population of approximately 1.25 million).

The study considered the material revenue reduction that would result from the loss of valuable materials (aluminum cans and PET bottles) recycled through a container redemption network instead of the MRF, as well as the impact of the change in throughput on fixed and variable costs related to MRF operations. (In general, fixed costs per ton will increase because the same equipment – with a set capital cost – is being used but the amount of processed material decreases.)

The findings, outlined in the table on below, confirm that moving materials from the MRF to the redemption system has real and substantial repercussions on MRF operating costs and revenues. According to the study, a highly effective deposit system – one that covers a broad range of beverages and employs a 10-cent deposit – would increase MRF costs by approximately $29 per ton, or $4.50 annually per household served. Under the contract structures currently in place for most of the country, these costs would be passed on to municipalities or ratepayers in the form of processing fee increases.

While a deposit system’s revenue effect on the average MRF ton is not substantial, the gross loss of material value may be, particularly if the overall throughput drops because materials moved out of the MRF to the deposit system are not replaced by greater volumes of other materials for recycling.

At the same time, it is important to note that these processing fee increases would be offset by savings in other parts of the municipal operating budget. For example, while some of the beverage containers redeemed in a deposit program would otherwise have been recycled in a MRF, even more eligible containers would have been thrown away as trash or litter. The study determined that the effective deposit system described above would result in more than 23,000 tons per year of waste being diverted from landfills in the model community at a disposal cost savings of more than $2.50 per household per year.

Other studies have also documented cost savings from reduced litter and marine debris cleanup costs. The Reloop “Reimagining the Bottle Bill” report, released in March, highlighted litter abatement cost savings of between $200,000 and $12.7 million for select states in the northeast U.S. Collection costs for both waste and recycling may also be reduced due to fewer materials flowing through those systems, but those savings would depend on a number of local variables, including routing efficiency and population density.

Nonetheless, even if the savings to municipalities outweigh the municipal processing cost increases, the sting of that higher sticker price on the recycling contract will still be very real. But this can be mitigated as policy is developed.

California’s Container Redemption Value (CRV) program, enacted after the development of curbside recycling in the state, is an example of a bottle bill that was built with an eye on the ripple effects felt by recycling stakeholders. The California framework allows MRFs to be paid the CRV value of the beverage containers they handle. Admittedly, the program has faced significant challenges related to the formula used to reimburse MRFs, as well as its impact on materials and markets. However, it offers a useful starting point for future policy discussions around MRF cost mitigation.

One key funding stream related to any deposit program is the unclaimed bottle deposits that stay in the system when containers do not move back into the redemption stream.

New bottle bills can require that some of the unclaimed deposit revenue be used to pay MRFs or municipalities for lost revenue or to reimburse them for the cost of handling the beverage containers that residents choose to put in their recycling bins. The amount of funding can be derived using a formula that considers the redemption rate in a given municipality and the number of containers processed through the MRF, or it can be based on documentation of pre- and post-deposit revenues and volumes. Alternatively, the amount can be based on the number of beverage containers recycled through the MRFs, as confirmed by third-party audits.

The addition of EPR

Looking globally, the highest performing recycling programs combine beverage container deposits with extended producer responsibility for packaging and paper products (EPR for PPP) to offer the convenience of curbside recycling, alongside the financial incentive and redemption network of deposits. These systems do not rely on government or ratepayer funding, but rather engage brands and consumer packaged goods companies (known as producers) to finance, and in some cases operate, the recycling system.

If a bottle bill is implemented or expanded in concert with EPR for PPP, the additional financial burden to municipalities is no longer a concern. Instead, producer responsibility organizations, formed to help producers meet their obligations under EPR and deposit programs, would determine how the costs of both the curbside and the deposit systems would be distributed among their members. MRF costs would also be covered by the producers.

The Canadian provinces of British Columbia and Quebec both have beverage container deposit programs and EPR for PPP that covers the full cost of recycling programs. The deposit program in Quebec will expand next year at the same time that producers transition to assume greater responsibility for processing of recyclables through agreements with MRFs in the province.

It should be noted the combination of bottle bills and EPR serves the needs of the producers as well.

Many brands have made commitments to use recycled content in their products and packages, yet our current recycling system is not delivering the quantity or the quality of materials needed to meet those goals. For example, according to projections from the National Association for PET Container Resources (NAPCOR), achieving 25% recycled content in PET packaging used in the U.S. by 2025 would require an additional 1.3 billion pounds of RPET – that’s more RPET than is produced from recycled bottles in the U.S. today, so we would effectively need to at least double PET bottle recycling to get there.

The PET, aluminum and glass recycled through bottle bills is more likely to be used in new packaging than material collected through other means because of its higher quality. The redemption system allows for source-segregated collection that reduces contamination and simplifies the recycling process, facilitating higher value end uses.

EPR, meanwhile, can bring new investment into recycling education, collection and processing systems to increase both the quality and the quantity of the materials recycled at curbside, making more material available to meet corporate goals. Increasing materials going to recycling means less material going to waste, which translates to less cost to municipalities, taxpayers and ratepayers.

A unique opportunity

Improving recycling in the U.S. is going to require change, and it is becoming increasingly clear that policy is needed to drive that change.

New policy should build on the experiences of the past three decades of recycling evolution, recognizing the limitations of a system that relies almost exclusively on local government resources and funding. Beverage container deposits are the most effective recycling program in place in the U.S. today. When crafted carefully, they can complement curbside recycling and create strong, high-performing programs, especially when they are strategically developed alongside EPR frameworks.

Policymakers currently have a unique opportunity to engage producers and consumers to improve recycling. At the same time, they can ensure that municipal programs are not hurt in the process.

Resa Dimino managing partner at Signalfire Group, a policy-focused subsidiary of RRS. She can be contacted at [email protected].

This article appeared in the April 2022 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.