This article originally appeared in the December 2017 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

When Resource Recycling first dove into the intersection of robots and recycling in a feature story in June of 2016, the movement was still in prototype mode.

At that point, machines were showing they could reliably pluck targeted materials off sort lines in lab environments, and the algorithm-based “brains” in their software systems seemed to hold big possibilities in enabling equipment to recognize and react to new materials in the stream. But questions nevertheless lingered about whether the technology would actually show up in working facilities in the near term.

Eighteen months later, such uncertainties have been tossed aside like dirty fiber on a PET line.

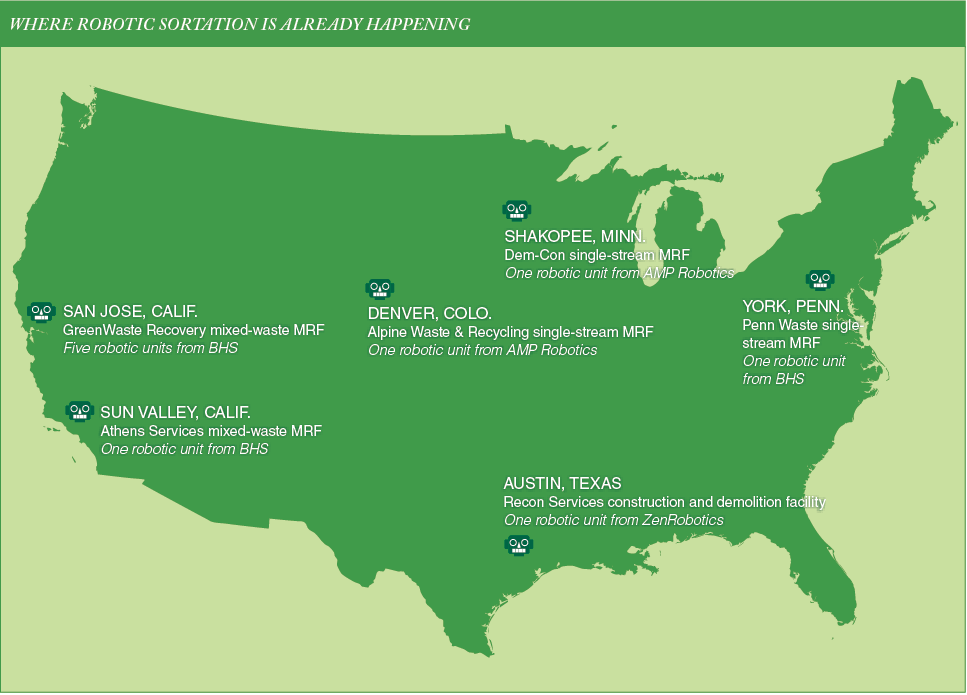

Sort systems relying on artificial intelligence (AI) are now working daily in at least six MRFs in the U.S. (see map below), and operators and equipment manufacturers have indicated more systems could be deployed soon.

Early adopters say that running on robotics makes economic sense because the sortation process is allowing them to maintain bale quality while reducing staffing requirements. In addition, according to some experts, the industry could soon start to see facilities designed to put robotic sortation front and center, a fact that would open the door to MRF designs and capabilities that are unheard of today.

Below, we lay out five key industry impacts that may be seen as AI sortation evolves.

1. Reduced reliance on manual sorters

One of the key elements pushing forward AI sorters is the fact that they have helped MRF operators in an increasingly challenging area: labor. With unemployment low across the U.S., MRF operators say the always-difficult task of hiring and retaining workers for manual sort slots has become even more of an issue.

“Our number one challenge is labor, getting enough people to the facility everyday,” said Bill Keegan, president of Dem-Con Companies, which this summer installed a robotic system in partnership with the Carton Council at Dem-Con’s single-stream MRF south of Minneapolis.

Keegan said at the time of deployment, unemployment in the local county was around 3 percent, and despite bumping up its advertised sorter wage by 10 percent, Dem-Con was still struggling to get a decent response to job postings. The MRF’s robot, from AMP Robotics, is replacing the 1.5 workers formerly needed to pull cartons off the line, and those employees have been moved to other sortation spots.

“This will help,” Keegan said of the AMP technology. “It will replace labor we haven’t been able to get.”

MRF operators interviewed for this story said they do not envision removing humans from materials processing completely. However, the economic and safety benefits that could come alongside continued robotic improvements may very well mean the jobs that do exist at facilities will be a step or two removed from the actual handling of material.

“One day the whole MRF will run much like a paper mill,” said Brian Wells of equipment manufacturer BHS, which rolled out an artificial intelligence system this spring. “It will all be run by sensors, with people in an air conditioned room making adjustments. Recycling’s never had anything close to that.”

2. Quicker adjustments on the line

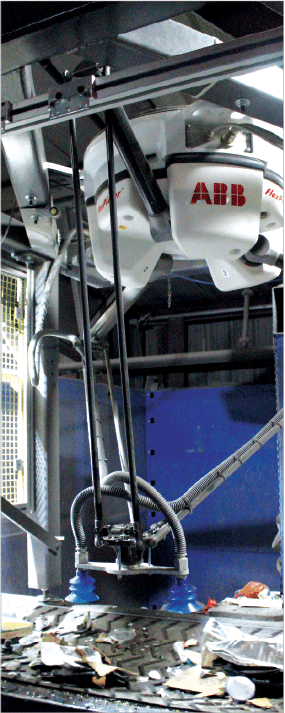

Today’s robotic sortation products work by using camera technology that has been around for years and pairing it with much newer computing advancements. The robotic tools visually scan every piece of material on the belt, quickly compare the characteristics to images that are stored digitally, and then take appropriate sortation action.

Aside from the actual separation of materials, this marriage of vision and data analysis means robotic systems are constantly creating rich pools of information about the materials moving through the facility. A number of operational benefits could come from leveraging this data.

For instance, if the vision component of the robot was set up at the very front of the line as well as at different points where materials are ejected, an operator could instantaneously determine what’s being lost and where.

Brent Hildebrand, vice president of recycling at Denver-area MRF Alpine Waste & Recycling, said at his facility, plant managers currently keep tabs on line efficiency by regularly checking on the mix of materials being sorted into bunkers at key points. But he said that system lacks precision, and the checks may not happen if managers have to deal with other issues.

Alpine was the first facility to start using an AMP robot, running a pilot program with the manufacturer and Carton Council through much of 2017. That pilot is now complete, but Hildebrand is continuing to use the robot at his facility, experimenting with new possibilities alongside AMP engineers. Hildebrand envisions a time when the robot’s data capabilities monitor line efficiency and automatically alert him when problems pop up.

“Let’s say the system fires up at 6 a.m. and I look at a report at 8 that’s saying we’re missing this much fiber over the first two hours,” he said. “We could then go and adjust the screens. … The data from something like that is massive.”

As robotics become more integrated with human machine interface (HMI) networks that allow operators to fine-tune processing systems, MRFs may more and more be able to tweak flows on their own.

“AI will know what’s out of balance and make adjustments based on data,” said Tim Horkay, director of recycle operations at York, Pa.-based Penn Waste, which installed a BHS robotic unit in the fall of 2017. “We want better quality, better throughput and better capture rates, and we need help to get there. We need computers because they can react to material faster than we can.”

3. Vastly improved knowledge of the stream

Those same data analysis capabilities can also help materials processors get granular on nuances within material categories.

Current optical sorters, for example, operate by detecting the specific type of material, such as PET plastic, that defines an item coming down the belt. But it can be advantageous to take sortation a step deeper, and robotic vision is a pathway to making that happen.

“On the PET stream, right now you’ve got a color sorter shooting off colored bottles,” said John Standish, technical director at the Association of Plastic Recyclers (APR). “Not just Sprite and Mountain Dew but also opaque mouthwash bottles. A robot could sort that color stream,” separating high-value items from material that should go into mixed bales or elsewhere.

Experts in AI sortation add that facilities could eventually start to use the material data to analyze the stream on a more macro scale, determining, for example, exactly how incoming loads differ day-to-day in terms of contamination and even showing exactly what types of items are sullying the stream. The MRF operator could then work with local recycling coordinators to try to address problems.

What’s more, the material-specific lessons learned at one facility could help inform others. Matanya Horowitz, founder of AMP, says a number of different AMP systems working at different MRFs around the nation might eventually be connected on a single network. If a new piece of packaging started showing up on one sort line, the robot there could spot it, learn to recognize and sort it, and then push the information out to others.

“So robots at another facility might learn the details before packaging even hits [that area],” Horowitz said. “The robots would pool knowledge, and an algorithm runs over all of it.”

4. Design around the robot

Right now, robotic systems are being used only for a few specific applications as MRF operators familiarize themselves with the technology’s capabilities and manufacturers fine-tune the equipment.

The BHS Max-AI robotic system helps to remove non-plastic containers from the PET container line at the Athens Services MRF in Southern California.

The BHS system is being used as quality control on PET container lines, pulling out aluminum and other items of value from the PET that has already been separated from other materials. Meanwhile, the AMP product, with backing from the Carton Council, is pulling cartons out of the mixed material stream near the end of the MRF line.

As the technology progresses, however, AI systems could take a more central role throughout the separation process. And as new MRFs are constructed, companies could start finding ways to boost efficiency and reduce building costs by designing the lines with robots in mind.

“The robot could be in places people can’t be,” said APR’s Standish. “This affects ceiling height and floor space requirements. Where we’re actually taking costs out, this could be very appealing.”

In addition, robotics could potentially fuel a trend of MRFs being built in smaller markets. Some experts say that cost realities associated with big pieces of heavy equipment and wages for workers have hindered the economic viability of smaller MRFs.

“Right now you need to handle a lot of material to justify the cost,” said Horowitz of AMP. “But if automation is small and modular, then you can have another approach. You’ll have MRFs no longer looking like they used to.”

Economic advantages in robotic systems can also come through the equipment’s ability to run continuously. Finland-based ZenRobotics has been installing its AI sortation product around the world at facilities handling construction and demolition (C&D) materials.

One of ZenRobotics’ most recent installations is at a company called Carl F in Malmoe, Sweden. At that site, human workers take care of some material preparation duties during the day as the robot sorts beside them. After workers clock out, the robot keeps chugging along.

“It’s the first plant designed exclusively for robots,” said Harri Holopainen, head of technology for ZenRobotics. “Typically recycling plants are quite large and need manual workers. So operating 24/7 is prohibitively expensive. Robotic sorting is allowing us to do something completely different.”

Holopainen added the momentum toward smaller sortation facilities could take automated materials separation to entirely new venues. He gave the example of cruise ships, which currently tend to incinerate the waste generated by passengers. A robotics-centered mini-MRF incorporated into the ship’s design could offer a more sustainable solution.

“That’s one case where robots could be a game-changer,” said Holopainen.

5. Better alignment with markets

Ultimately, success in material processing comes down to finding ways to maximize the value of material coming into the MRF. And it may be in this arena that robotics hold some of their greatest power.

Through a Carton Council pilot project, the AMP Robotics system has been installed at MRFs in Colorado and Minnesota.

Recycling markets are defined by fluctuation, and the best MRF operators are skilled at making constant adjustments to take advantage of a high price for one material or reduce emphasis on another if values drop. AI systems have the capability to transform such decision-making.

Currently, for example, the BHS robot allows an operator to set a hierarchy of value, wherein a handful of different materials are programmed in, and the machine prioritizes one type over another based on instructions from the operator.

“Eventually, that prioritization will be automated,” said Wells of BHS. “Plant operators will put market values into the system and then AI will determine on its own what is worth its while.” The machines could even be synced up with incoming market reports, recognizing when value shifts occur and making changes to what gets prioritized during sorting.

The systems could also help solve the “chicken and egg” conundrum that inevitably comes up amid efforts to develop markets for newer packaging and other materials.

Often, potential downstream buyers won’t commit to taking on a recovered material type until they know sufficient tonnages can be reliably provided by the processor, but processors are hesitant to devote man hours to a new stream until they know they can move the material at a profit.

The economic and speed advantages of robots when compared with human labor could be the difference that enables the industry to move forward on this impasse in certain scenarios.

“Could robots better manage films that get into MRFs?” asked Standish. “Could they help manage the flexible [plastic] stream? Who knows where the biggest impact is going to be seen. It’s crazy to not do everything we can to create opportunities and let innovation move ahead as fast as possible.”

Dan Leif is the managing editor of Resource Recycling and can be contacted at [email protected]