In Toronto, as in other cities, multi-family residential recycling rates have been stubbornly lower than their single-family counterparts. As Canada’s largest city works to boost recycling rates, a local MRF operator is experimenting with recovering recyclables from multi-family garbage streams.

Toronto, Ontario

Two presentations at WasteCon 2017 in September in Baltimore touched on the recycling environment in Toronto. One came from Jim McKay, general manager of solid waste management services for the city of Toronto.

The other perspective was offered by Jake Westerhof, vice president of corporate strategy for Canada Fibers. He covered his company’s new mixed-waste processing project, which he said shows promise for boosting multi-family recovery rates. But he was also adamant about the fact that the mixed-waste strategy, in which recyclables are sorted from trash at the MRF, is only one segment of a wider diversion plan.

“We want to be clear that, for us, mixed-waste processing is not a replacement for source-separation programs,” he said. “Mixed-waste processing is a complement to source-separation programs. The fact is the black bag still has organic material and recyclables in it.”

Unique set of factors

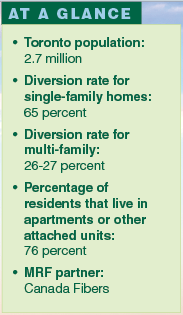

With a population of 2.7 million, Toronto boasts a 65 percent diversion rate (not including contamination) in its single-stream, single-family program, McKay said. But the number falls to around 26 percent for multi-family, something the city wants to address.

While multi-family recycling performance lags curbside single-family in most communities, Toronto faces some unique challenges. It has a very high percentage of apartment dwellers. According to Statistics Canada, only 24 percent of the city’s population lives in single-detached houses. Around 44 percent live in apartment buildings that are five or more stories tall, and nearly 32 percent live in shorter apartment buildings, row houses, duplexes and other attached dwellings.

McKay also noted that more than half of the city’s population wasn’t born in Canada, which presents language and cultural barriers in communications. The municipality also has a lot of high-rise buildings built in the 1960s and ‘70s that sport only garbage chutes.

Over the past few years, the city has learned some lessons the hard way. “We tried to apply a single-family model to multi-family buildings, and that hasn’t worked,” McKay said.

While buildings may look the same, the demographics can vary, he noted. “We really have to go building by building to identify what their needs are,” he said.

One change that has been successful is converting the buildings’ garbage chutes to source-separated organics chutes. Residents still have to carry their dry materials downstairs – both garbage and single-stream recyclables – but they don’t have to keep the putrescible materials around long.

Nevertheless, the city has been looking for fresh concepts on the multi-family front, and that’s where Canada Fibers has come in.

The 27-year-old vertically integrated company runs more than a dozen MRFs, including the largest in Canada: a five-year-old facility that sorts all of Toronto’s 200,000 metric tons of single-stream material annually.

Upstream, the company is involved in collection. Downstream, it runs processing facilities that make recycled products, including one in Toronto producing compounded PE and PP pellets and washed PET flake.

In all, it handles about 1 million metric tons of material annually, including about half of Ontario’s curbside material.

Tinkering with mixed-waste processing presents “a completely different animal,” Westerhof said. Understanding the framework in Ontario is important, he said, because he doesn’t want people to think program leaders are “absolutely whacko” in what they’re trying to do with mixed-waste processing.

Political mandates are driving higher recycling performance standards in Ontario, but the needle seems stuck at around 50 percent, Westerhof said, which has led stakeholders to start thinking about material that’s being missed in source-separation programs.

He noted that for multi-family housing, about 40 percent of the garbage stream is organics and about 10 percent is recyclables. Another 20 percent could be turned into an alternative, low-carbon fuel, while the rest is residual destined for disposal.

Canada Fibers last year began its first foray into mixed-waste processing. It embarked on a phased approach so it can learn and avoid big mistakes along the way, Westerhof said.

Canada Fibers last year began its first foray into mixed-waste processing. It embarked on a phased approach so it can learn and avoid big mistakes along the way, Westerhof said.

“The highway is littered with casualties in mixed-waste processing,” he said. “I’m sure everybody knows the names.”

Results of pilot project

Last year, Canada Fibers conducted two six-week pilot projects in which a total of 5,000 metric tons of material were handled. Using MSW sourced entirely from multi-family housing, the facility achieved 40 percent diversion of organics and recyclables (about 35 to 36 percent organics and 4 to 5 percent recyclables, which were made up of ferrous and non-ferrous metals, PET, PE and PP).

“Paper and paperboard were contaminated sufficiently that they were not able to be marketed,” he said. “We weren’t surprised by that.”

Urban Polymers, Canada Fibers’ sister company, took all of the recovered plastics. Because they were dirtier than those from a conventional MRF, Urban Polymers didn’t particularly like taking them, Westerhof said, but they were still able to recycle them.

Starting in late February, Canada Fibers embarked on a larger test. This time, it took 15,000 metric tons of MSW feedstock consisting of 65 percent multi-family and 35 percent single-family material. The facility ran at 22 tons per hour, purposefully dialing it down to get the separation outcomes the company sought, Westerhof said.

The effort recovered about 40 percent of the stream, he said. Of that recovered faction, just under 90 percent was organics, around 8.5 percent was metals and the rest was plastic. After processing the organics, the downstream digesters reported the feedstock had about 80 percent of the gas content they’re used to getting from source-separated organics, a number they were happy with, he said.

Still, Canada Fibers probably hasn’t figured out all of the metrics yet, he said, noting that the organics downstreams are hinting that they’re going to need more money in their pockets to manage the material. Canada Fibers also wants to invest to increase the quality of the organics fraction.

Officials are also still tinkering with the low-carbon fuel fraction and plan to test loads of it with cement producers.

Additionally, Canada Fibers plans to make further investments to increase the overall recovery at the facility. Westerhof said he thinks 40 percent recovery is a good step, but, in his mind, 50 percent or above is “what’s needed to be a winner.”

Think your local program should be featured in this space? Send a note to [email protected].

This article originally appeared in the November 2017 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.