This story originally appeared in the January 2017 issue of Resource Recycling.

Subscribe today for access to all print content.

In September 2015, organics recovery in the United States experienced a watershed moment.

The U.S. EPA and the U.S. Department of Agriculture together issued a national goal of reducing food loss and waste by 50 percent by the year 2030. It was a striking signal that some of the nation’s top policymakers had begun viewing the tonnages of food going to landfill and other forms of disposal as a significant issue – and one they were willing to put energy into solving.

“Let’s feed people, not landfills,” EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy memorably said at the time of the goal announcement. “By reducing wasted food in landfills, we cut harmful methane emissions that fuel climate change, conserve our natural resources and protect our planet for future generations.”

The 50 percent reduction initiative showed the time had come to address food recovery in a more aggressive and systematic way across the U.S. And though the election of Donald Trump to the White House raises major questions about the leadership role federal agencies will play in coming years on this front, the momentum around curbing food waste is now coming from various organizations outside of government as well.

In May 2016, for instance, a coalition of government, business and nonprofit stakeholders called ReFED issued a roadmap to reducing the nation’s food waste by 20 percent in 10 years. And in November 2016, the National Waste & Recycling Association (NWRA) published a white paper called “State of Organics Recovery,” which outlined the facts around the estimated 52 million tons of food scraps disposed of in the U.S. annually.

The question now is: How do we actually make progress on the food waste issue? Not surprisingly, there is no single answer. The keys to success will likely involve coordinating local initiatives and best practices and, of course, developing markets for material.

Limited action from legislatures

It seems logical that to truly lift the recovery of food and organics on a grand scale, legislation at the state level will need to play a role. “Increased emphasis on managing organics from other municipal solid wastes is inevitable as states continue to look for ways to increase diversion of materials from disposal,” the recent NWRA organics white paper noted. “Organics clearly offer the most promise and the biggest challenges to increase diversion.”

To some degree, individual states have already helped set the tone when it comes to the food scraps side of organics management.

Currently, five states have laws on the books that ban food from being disposed of under certain conditions. For example, in California, businesses generating 8 cubic yards or more of organic waste per week are required to arrange for recovery services. The mandate was put in place by legislation signed in 2014, and over the coming years, the law will expand to include more generators.

In Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Vermont, meanwhile, certain commercial and institutional generators are banned from disposing of organic materials. In Vermont, the prohibition is set to extend to residents in 2020.

In Connecticut, Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Vermont, meanwhile, certain commercial and institutional generators are banned from disposing of organic materials. In Vermont, the prohibition is set to extend to residents in 2020.

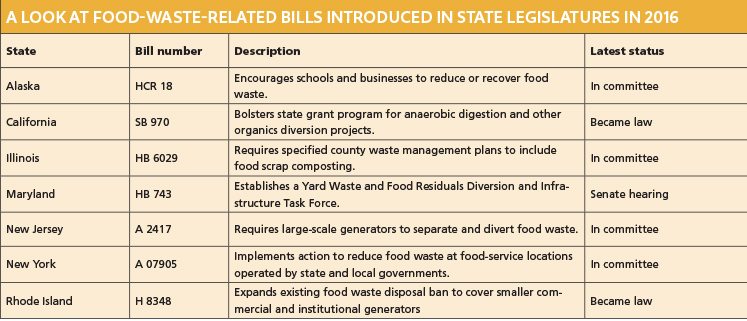

However, a Resource Recycling analysis of food-waste legislation introduced at the state level nationwide showed very limited activity over the past year (see table above).

Rhode Island passed a bill in July that expands the pool of businesses and institutions covered by the organics disposal ban, and California passed a law in September that aims to bolster state grants for anaerobic digestion and other projects aimed at organics diversion.

But not much else was considered. Alaska, Illinois, Maryland, New Jersey and New York each saw one bill aimed at addressing food waste, but all of those failed to move out of the committee stage, according to the analysis.

It’s also important to note that a federal bill was also introduced amid the recent interest in the food diversion, but it too failed to gain much traction. The Food Recovery Act of 2015 was introduced in the U.S. House of Representatives on Dec. 7, 2015 by Rep. Chellie Pingree, D-Maine. The legislation aimed to create a federal grant program providing up to $100 million a year to build large-scale composting and anaerobic digestion facilities. The bill was referred to several committees and never advanced.

If the country wants to see a 50 percent reduction by 2030, it seems, the incentives and initiatives may need to come from outside the legislative realm.

Looking local

If state action remains limited, perhaps food diversion leadership will come from city leaders. Many concrete steps toward boosting recovery of food and other organics have occurred at the municipal level in recent years.

For instance, by mid-2015, more than 100,000 households were receiving organics collection in New York City, with collected material heading to two composting facilities north of the city, according to the New York Times.

America’s most-populous city has been part of a long-developing trend seen around the country. According to a study from organics industry publication BioCycle, 198 U.S. municipalities had curbside collection of food scraps in 2014, up from 24 in 2005. Those nearly 200 programs covered 2.74 million households.

And innovative thinking on organics among local leaders is constantly developing. At the Resource Recycling Conference last September, Gretchen Wolfe from the City of Phoenix described the city’s persistence in finding a way to keep major tonnages of palm fronds out of the waste stream.

After some initial frustration in the search for a solution, the City inked a 10-year deal with a company called Palm Silage, which will build its manufacturing facility at the city’s Resource Innovation Campus. Phoenix will pay $12 a ton to deliver Palm Silage the fronds, saving $5 a ton compared with landfilling. At the same time, the company will pay the city rent, and Phoenix took a solid step toward its 40 percent diversion goal (remarkably, palm fronds account for 3.4 percent of the city’s waste tonnages).

“We will instantly move our needle if we can make this work,” Wolfe told the audience at the conference.

Creating the types of markets Phoenix was able to solidify will be a critical piece of any advancements toward robust recovery of food scraps and other organics in the U.S. Unlike aluminum, PET plastics and other long-targeted recyclable materials, diverted organic material cannot be cost-effectively shipped across the ocean or across the country for final processing. As is also the case with recovered glass and a number of other materials, local materials will need local solutions.

The NWRA’s organics report estimated 6.7 million tons of food will need to be recovered annually through composting, anaerobic digestion or wastewater treatment facilities to meet the recovery goals laid out by the ReFED project. To hit the federal 50 percent reduction goal, even more will need to be diverted or source-reduced.

“Whether food waste will be managed through composting or anaerobic digestion or other processes, the food waste must be collected,” the NWRA report stated. “Then it must be processed at facilities permitted to handle those materials. Regardless of who set the goal, all the goals for organics recovery – including the EPA/USDA goal of 50 percent food waste reduction by 2030 – require a massive new infrastructure and considerable effort on educating consumers on how to avoid creating organics waste, food waste in particular, and then how to best manage it.”

That’s essentially where the push for food waste diversion sits now: major aspirations but a great need for generator education, processing capacity and more downstream innovation.

A multifaceted market

For a case study on how the pieces of market development could come together, the industry can look to California. There, statewide initiatives to increase diversion of food scraps and other materials have been buttressed by local pushes, such as the municipal program in San Francisco that collects more than 600 tons of residential organics daily.

In addition, in 2015, California passed a significant piece of legislation, AB 876, that requires local governments to report to the state where new or expanded composting operations could be sited. The law was a signal of the state’s desire to be proactive when it comes to developing its organics infrastructure.

With substantial tonnages now reliable in many areas of the Golden State, entrepreneurs have emerged to consume it. In October 2016, for instance, a company called California Safe Soil opened a facility in the Sacramento area capable of taking in 32,000 tons of material annually for use as feedstock in the company’s production of liquid fertilizer.

Another example of business innovation based on discarded food can be seen in the development of Full Cycle Bioplastics, a Richmond, Calif.-based startup that consumes food waste and other organics to produce PHA, a biodegradable plastic resin. The company’s CEO, Andrew Falcon, recently told Resource Recycling that the Full Cycle bio-refining process can be used by food companies and other food scrap generators to help them turn a waste product into a higher-value material. He cited Taylor Farms, a vegetable processor and bagged-salad retailer based in Salinas, Calif., as an example.

“They could take their own agriculture food waste from their manufacturing process, convert it into PHA biopolymer and then have that PHA biopolymer used to make a bag that they could sell their lettuce in on the retail shelf,” Falcon said.

It’s true Full Cycle has not yet been fully commercialized, and it faces plenty of its own market challenges in the competitive plastics arena. But if the nation’s great food waste reduction aspirations are to be realized, unique entrepreneurial and municipal approaches will need to considered and supported.

The food waste problem has been identified and quantified. The goals have been set. Now it’s time to put words into action.

Dan Leif is managing editor at Resource Recycling and can be contacted at [email protected]. Resource Recycling staffers Lacey Evans and Jared Paben contributed reporting for this article.