This story originally appeared in the February 2016 issue of Resource Recycling.

Subscribe today for access to all print content.

Across the country over the past several years, collection of food scraps at the curb has been a trend on the rise. Normally, communities ask residents to begin adding food to carts previously used for yard debris only, or they bring another container into the mix. However, other possibilities could make collection more efficient.

In California in 2015, two food scrap recovery pilot programs were implemented leveraging split-body carts. The idea was to separate food material from plant trimmings so as not to contaminate loads headed to the green compost industry. The concept was first proposed by this author in a 2012 Resource Recycling article, “A modest proposal.”

The pilot programs, detailed below, indicate that a split-cart model for food scrap collection can, in fact, make a major difference in the tonnages and quality of organic material diverted.

A city with split-cart experience

In March 2015, the City of Sunnyvale, Calif. implemented a nine-month pilot food-scrap recovery program using split-body carts.

The idea was hardly ground-shaking in that municipality. Prior to the pilot effort, Sunnyvale already used a 64-gallon split-body cart for recyclables (with fiber on one side and other recyclables on the other), and the basic residential waste management service relied on a 96-gallon wheeled cart for collection of plant trimmings, and three sizes of carts for garbage – residents were offered 32-, 64- and 96-gallon options.

Sunnyvale maintained this dual-stream recycling program using a split-body cart even when most communities in the area switched to single-stream recycling. So when it came to collecting food scraps, it was not unreasonable to ask residents to also keep their wet, compostable wastes separate from other household garbage.

All of the materials collected by Specialty Solid Waste & Recycling, the city’s franchised hauler, are delivered to a facility called the SMaRT Station. This site processes recyclables for market and plant trimmings for compost, and it also processes mixed waste for recovering recyclables that had been placed in garbage containers. The waste that remains is placed in long-haul transfer trailers for disposal at landfill.

For the pilot program, five service areas, each with just over 100 households, were selected to test the new concept in different demographic areas. In each of the pilot areas, residents were asked to put food and food-soiled paper from the kitchen in one side of the cart, and all other household garbage (including pet waste and disposable diapers) in the other side of the cart. Residents were asked to continue managing their plant trimmings and recyclables in the same way as before the pilot. The single-compartment garbage carts were replaced with split-body carts that matched the recycling carts but had different colored lids.

Most households were given 64-gallon garbage carts, with 32-gallon capacity on each side. Households that generated more garbage than would fit in the 64-gallon cart were provided a split 96-gallon cart. Sure-Close kitchen pails were provided to households when the split-body carts were delivered. Near the end of the pilot, a different cart – one in which 70 percent was devoted to trash and 30 percent to food scraps – was tested in one of the five pilot areas.

Just over a year ago, the City replaced its old 64-gallon split recycling carts with new carts and saved more than 500 of the old carts for this pilot. The City also paid for the 500-plus kitchen pails used in the pilot initiative, leveraging funding it had received to implement zero waste programs. It will cost roughly $3 million to go citywide with split 96-gallon carts for garbage and food.

To complement the cart distribution, a series of promotional materials were distributed in the pilot areas: A letter from the city was sent out to all of the households, and post cards, fliers, cart-hangers and a website were used to communicate details of the program to the residents in the pilot areas.

A third of waste diverted to compost

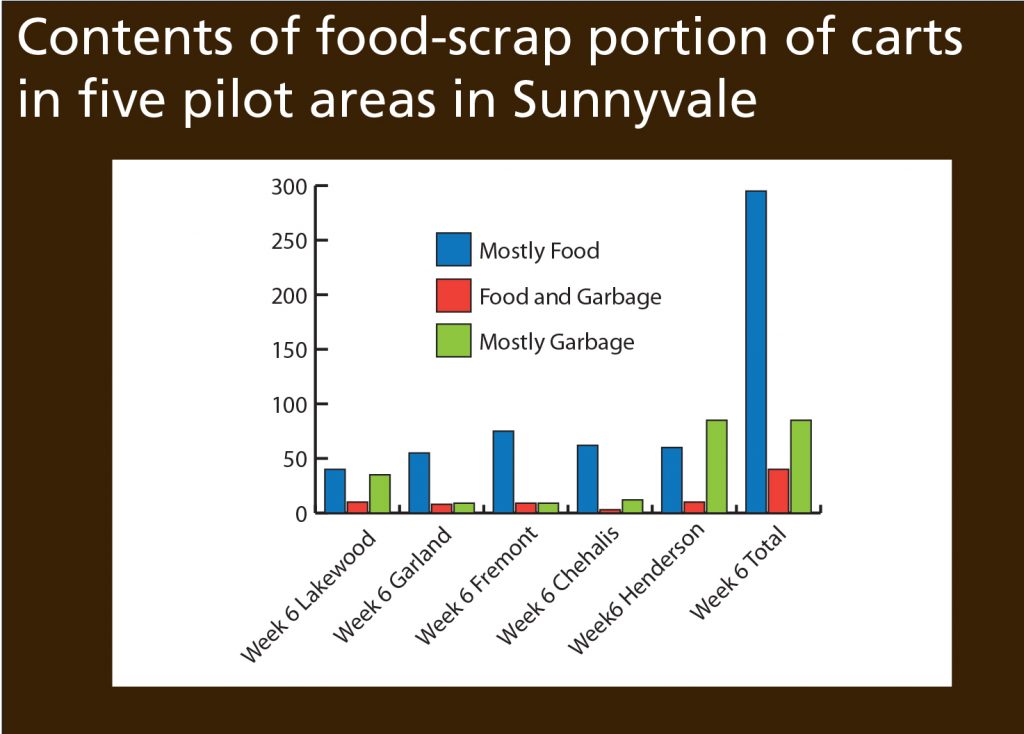

Field audits were conducted to determine the contents of the split-body carts set out for collection in Sunnyvale from March through December 2015. City staff would go out before the collection vehicle and flip the lids on both sides of the garbage carts and look for participation and contamination. On selected weeks, tags would be left on each cart, either thanking residents for doing a good job separating their food scraps, or asking them to do a better job separating their organics from other waste.

In addition, on various dates throughout the pilot, loads were inspected as they were received at the SMaRT Station. These inspections found households separated an average of 12.6 pounds of food scraps each week. In other words, the pilot program successfully diverted one-third of the waste that single-family residents had been putting in their garbage carts.

The measurement continued near the end of the program time frame. A sample consisting of the contents from eight split-body food scrap and garbage carts from each of the five pilot areas was collected. The contents of both sides of the carts were sorted and weighed.

From that assessment of single-family households in the pilot areas, the following statistics emerged:

- An average of 12.6 pounds, or 75 percent of all food scraps, was correctly placed in the food-scrap side of the cart.

- Only two of the 40 carts sampled had significant amounts of garbage in the food-scrap side.

- Over 90 percent of the single-family households in the pilot areas participated.

Furthermore, there was considerable variation in the size of the loads of materials collected in each of the pilot areas. The area with the largest average family size generated, not surprisingly, the most food-scrap material. The smallest households had less than half as much food material as the largest households.

A final telling finding was this: Around 85 percent of the material in the food-scrap side of the split-body garbage carts was compostable. Most of the remaining materials were the plastic bags that were used to contain the food scraps in the residents’ kitchens. All of the samples examined were able to be fully processed at the SMaRT Station.

Adding food scraps in San Jose

Based on the success of the Sunnyvale split-body cart pilot project, the City of San Jose and Garden City Sanitation (GCS), the garbage collection firm serving most of San Jose, have implemented a similar pilot program. The initiative launched on Sept. 15, 2015 and will run for a year.

Based on the success of the Sunnyvale split-body cart pilot project, the City of San Jose and Garden City Sanitation (GCS), the garbage collection firm serving most of San Jose, have implemented a similar pilot program. The initiative launched on Sept. 15, 2015 and will run for a year.

San Jose residents have grown accustomed to putting their recyclables in light gray carts, their garbage in black carts, and their plant trimmings loose in the street. Since the plant trimmings are not containerized, the City cannot co-collect food scraps with yard trimmings, so waste officials needed another option.

Garden City Sanitation is using a patented auger technology in its collection vehicles for the split-cart pilot project. The existing fully automated side-loading collection vehicles have been retrofitted with an auger insert, which includes a split hopper that allows two types of materials to be collected at the same time.

The pilot program is testing two types of carts for residential food scrap collection. One is a newly designed split 64-gallon garbage cart, with a 48-gallon section for garbage on one side and a 16-gallon section for food scraps on the other. The extra garbage capacity (the 48-gallon garbage section is an increase from the 32-gallon carts most customers currently use) aims to limit contamination in both the food scraps and single-stream recyclables. Around 2,600 homes received the split cart.

The other option being tested is a separate 20-gallon food scrap cart to be used along with the existing garbage and recycling carts. Residents in this pilot area, which includes roughly 4,000 homes, have been asked to put only food scraps in the new container. Again, the addition of the extra cart increases the level of service as a way of reducing contamination.

The San Jose pilot route areas were selected so that the collection days remain unchanged, and the additional service is provided at no additional fee to the participants.

Garden City Sanitation is covering the cost of the 2,600 split carts, 4,000 small carts and 6,600 kitchen pails used in the program. If the program goes citywide, it will be funded through residential rates.

Early San Jose results are now being tallied. The participation rates for the split carts went from 68 percent (garnering a total of 111 tons of food-scrap material) in late September to 63 percent (190 tons) in October. For the small-cart pilot, participation went from 41 percent (33 tons of material) in late September to 38 percent (45 tons) in October.

Early San Jose results are now being tallied. The participation rates for the split carts went from 68 percent (garnering a total of 111 tons of food-scrap material) in late September to 63 percent (190 tons) in October. For the small-cart pilot, participation went from 41 percent (33 tons of material) in late September to 38 percent (45 tons) in October.

From curb to animal feed

In the San Jose program, the split-body collection vehicles are used to separately collect organics, meaning the material remains clean and ready for processing.

The food scraps recovered in the two pilot areas are delivered to Sustainable Organics Solutions (SOS), a sister company of GCS. The food scrap processing facility was designed and engineered by Louie Pellegrini, the GCS president.

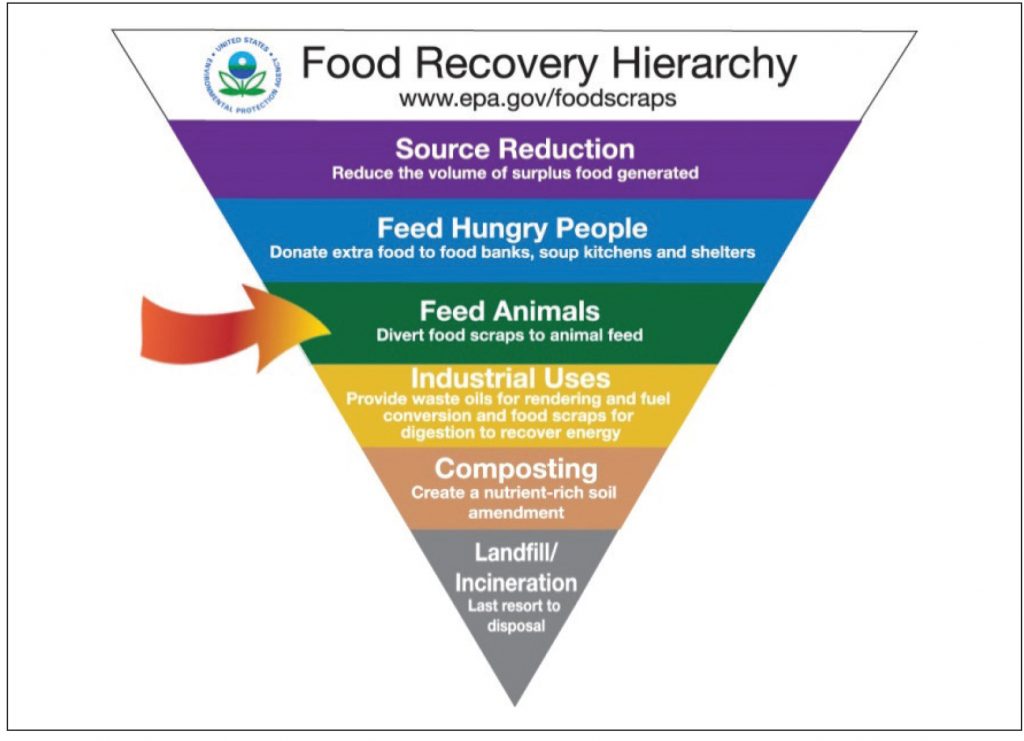

SOS produces high-value, high-quality animal feed from post-consumer food and food waste generated from food packaging processes that cannot be used to feed people. As shown in the graphic, SOS’s approach aligns with the EPA’s Food Recovery Hierarchy, in which processing food waste into feed for animals is preferred to recovering it for industrial uses, composting, incineration or landfill.

Processing the collected material is a two stage process. In the pre-processing stage the truck is unloaded into a hopper. Material is conveyed to a shredder and then on to a screw-press at the end of the pre-processing. The press is designed to remove contaminants and convert the food scraps into a mash consisting of approximately 25 percent solids. The contaminants are discharged from the screw press into bins, and the liquid mash is pumped to refrigerated storage tanks and then transported to the SOS animal feed production facility. Pathogens in the mash are destroyed using a patented drying and sterilization process that does not destroy the nutrient value.

Three separate and valuable products are produced from the incoming organics: water, FOG (fat, oil and grease) and dry meal. Almost 200 gallons of water and 20 gallons of FOG are extracted from each ton of mash, and the roughly 500 pounds of solids become the dry meal product.

The end result of the process is a nutrient-rich product with approximately 20 percent protein, which meets U.S. Department of Agriculture feed requirements for animals such as pigs, chickens and dogs.

Beyond finding a high value use for discarded food, this program can also help limit the use of land, water and other resources required in the production of virgin crops for animal feed. And, because the materials are processed quickly, the large facilities and acres of storage land required for composting and anaerobic digestion facilities are not needed.

Another tool in the organics movement

The Sunnyvale and San Jose efforts show that using split-cart and split-truck methodology can greatly boost the efficiency of food-scrap collection in certain areas of the country. Finding innovative ways to move clean organic material out of the waste stream helps communities move toward environmental goals, and the split-cart model does so without demanding unreasonable changes from residents. This is a tool to be considered as the organics movement pushes forward.

Richard Gertman is the principal of For Sustainability Too. He can be reached at [email protected].