This story originally appeared in the January 2016 issue of Resource Recycling.

Subscribe today for access to all print content.

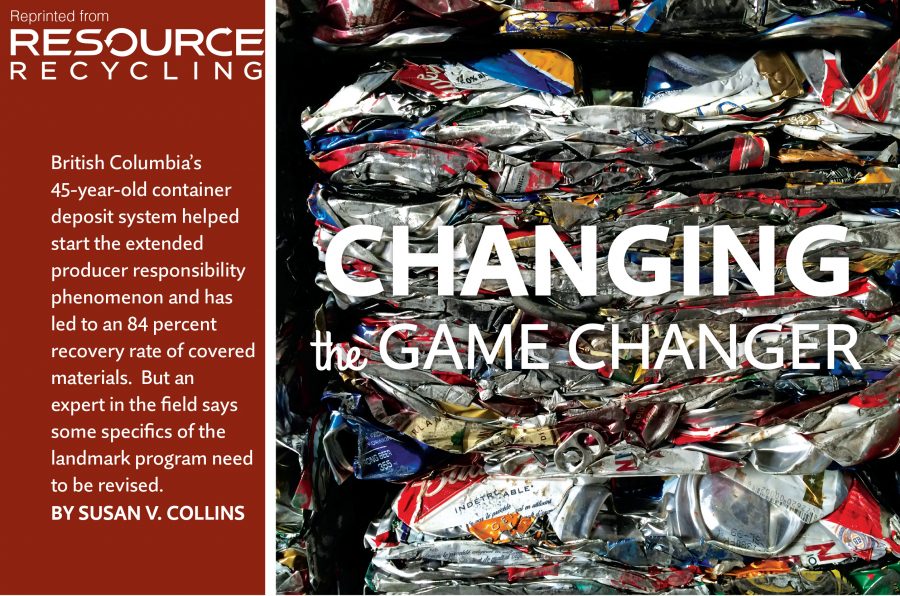

The history of global extended producer responsibility (EPR) programs dates to 1970, when the Canadian province of British Columbia passed legislation establishing the province as the world’s first jurisdiction with a mandatory refund system for soft drink and beer containers.

Over the past 45 years, the B.C. EPR program law has grown to cover all container types and all beverage types except milk, with an overall recovery rate of 84.2 percent, which is significantly higher than the 75 percent legislative target recovery rate. It also has helped spur growth in the recovery strategy globally, with more than 40 container deposit programs operating worldwide as of mid-2015.

But, as with any program, there’s always room for improvement. At the Container Recycling Institute (CRI), where our mission is to make North America a global model for the collection and quality recycling of packaging materials, we recently completed a comprehensive report titled “The Environmental and Economic Performance of Beverage Container Reuse and Recycling in British Columbia, Canada.” The report plays an important role in expanding our body of research on best practices in this field.

While showcasing the impressive accomplishments of the B.C. program, our analysis raises several concerns – including unprecedentedly high container recycling fees (CRFs), a lack of transparency in financial reporting and a bloated reserve fund – and provides recommended improvements to enhance this high-performing program.

Early example of EPR

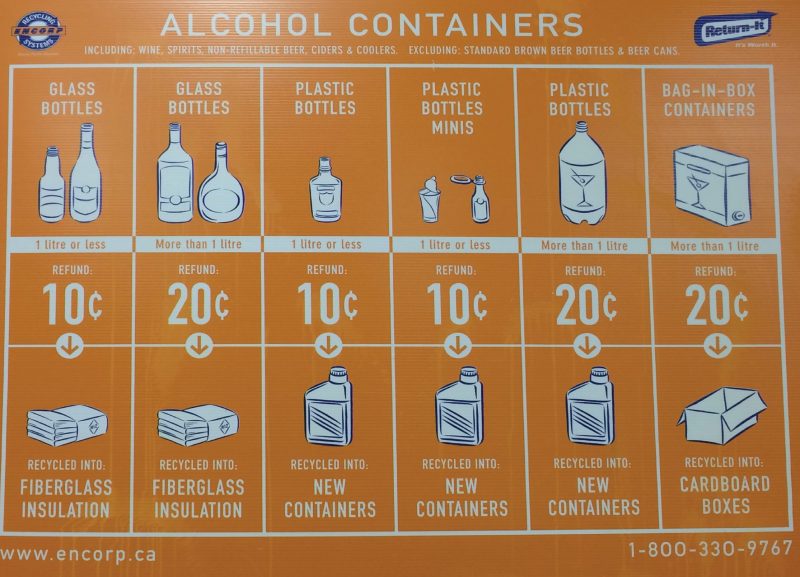

Private stewardship agency Encorp has developed signage to help British Columbia residents better understand the recycling chain.

While B.C.’s Container Deposit-Refund Law initially was viewed strictly as a litter control initiative, it was the first example of what is known today as a legislated EPR program. Definitions of EPR can vary across the materials management industry, but the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development defines extended producer responsibility as an environmental policy approach in which a producer’s responsibility for a product is extended to the post-consumer stage of a product’s life cycle. In this sense, the B.C. program would be classified as EPR (see sidebar on page 39 for details on the role of producers).

The program applies a deposit (5, 10 or 20 cents) on nearly all packaged beverages sold in the province, with convenient return-to-retail, depot and other consumer return options. In the program, refillable beer and cider glass bottles are washed and refilled an average of 15 times, with nearly a 100 percent return rate.

Additional program benefits include:

- Keeping 123,000 tons of material from the landfill each year

- Creating hundreds of jobs in collection, processing and recycling

- Saving money for municipalities in avoided litter collection costs

- Keeping waterways and roadways cleaner due to litter reduction benefits

- Avoiding as much as 20 percent of the greenhouse gases that otherwise would be generated by B.C.’s divertible waste stream, given the emissions impacts of beverage container production (especially metal and plastic)

Responsibilities for the program are split between two private stewardship agencies formed by B.C.’s beverage producers. These agencies are Encorp Pacific (Canada) and Brewers Distributor Ltd. (BDL), and both entities answer to B.C.’s Ministry of Environment (MOE), which carries out B.C.’s Recycling Regulation. Encorp oversees container recovery for all soft drinks, water and other nonalcoholic beverages as well as all wine, spirits, beer and cider sold in non-refillable glass bottles. BDL covers all alcohol sold in cans, plus beer and cider sold in refillable glass bottles.

Responsibilities for the program are split between two private stewardship agencies formed by B.C.’s beverage producers. These agencies are Encorp Pacific (Canada) and Brewers Distributor Ltd. (BDL), and both entities answer to B.C.’s Ministry of Environment (MOE), which carries out B.C.’s Recycling Regulation. Encorp oversees container recovery for all soft drinks, water and other nonalcoholic beverages as well as all wine, spirits, beer and cider sold in non-refillable glass bottles. BDL covers all alcohol sold in cans, plus beer and cider sold in refillable glass bottles.

The two agencies handle program funding differently. Encorp charges consumers an external, non-refundable CRF, over and above the fully refundable deposit. Stewards that charge a visible – also called “eco” – fee must provide financial audits regarding how these fees are used. BDL does not charge an external CRF, instead embedding its program costs into beverages’ shelf prices.

Concerns and recommendations

CRI continues to recognize the achievements and benefits of B.C.’s beverage container recycling system, but our report notes several areas of concern. In assessing these, we provide recommendations that, if implemented, can strengthen this program moving forward.

BDL’s program does not charge consumers a separate recycling fee and recovers secondary packaging (primarily cardboard) in addition to beverage containers. The main area identified for improvement is expansion of unlimited consumer return coverage.

Encorp’s program charges separate recycling fees, with more than $50 million collected annually from consumers. From 2009 to 2013, the number of containers recovered by Encorp dropped by 9 percent, while between 2008 and 2013, the CRFs collected from consumers increased by more than 60 percent. The paragraphs below outline specific concerns and recommendations regarding Encorp’s program participation.

High CRF fees: Encorp charges some of Canada’s highest CRFs, including 35 cents for glass bottles larger than one liter. This is three times the highest fee in any other province, though Encorp does note that this category represents an extremely tiny part of its recovered containers (about .015 percent). However, the fee is still emblematic of the higher (and growing) CRFs in British Columbia – CRFs in neighboring Alberta max out at 8 cents per container – and points to an unusual practice that allocates transportation costs by weight rather than volume. Furthermore, Encorp charges more for non-alcohol beverage containers than for alcohol containers that otherwise may be identical.

CRI’s recommendation: Encorp should examine its cost allocation methodology and consider benchmarking its fees against other Canadian container deposit programs. In addition, assigning transportation costs by weight instead of volume almost certainly results in over-estimating the actual cost to collect and recycle heavier containers – and underestimating the actual cost to recycle lighter, bulkier ones.

Financial Transparency: The presentation of financial data in Encorp’s annual report makes it impossible to know exactly how much its beverage container recycling program costs, and does not provide sufficiently transparent financial information. In addition, Encorp’s CRFs are determined by Encorp with no ministry approval required, leaving consumers no recourse to pursue any desired change.

CRI’s recommendation: Encorp’s annual report should include revenues and expenses separately for the beverage container recycling program and not commingle them with those for its electronics recycling initiative. This will allow the MOE and consumers to determine if the CRFs are reasonable. In addition, Encorp should report key financial indicators over time, such as cost per container sold and cost per container recycled, allowing the ministry to further evaluate the program and seek continuous improvement to provide consumer protection.

Reserve Fund Level: As Encorp’s CRFs have steadily risen, its reserve fund has grown far beyond the $17 million it has calculated as a “prudent” level. By the end of 2014, the reserve stood at nearly $34 million.

CRI’s recommendation: With the MOE, Encorp should set CRFs at a rate that will not cause the reserve to grow beyond a reasonable level, meaning a calculated amount based on costs determined for identified risk factors (such as potential scrap-material-market price fluctuations and redemption rate changes). These risks have not materially increased since Encorp’s 2013 annual report identified $17 million as a prudent reserve, yet the reserve has doubled. This is important because CRFs are designed to place all program costs on consumers, not on the beverage producers.

Transportation Costs: The combined costs for transportation and processing in B.C. are, on a per-container basis, more than twice as high as the equivalent line item in Alberta: 2.3 cents versus 1 cent. Transportation and processing costs in Encorp’s program exceeded $22 million in 2013, making this the agency’s second-largest expense after the handling fees paid to collection depots and retailers.

CRI recommendation: While the issue of transportation costs is beyond the scope of our report’s research, and merits further study, Encorp should assess this issue, perhaps by benchmarking with other container deposit programs or consulting logistics experts. For example, in other jurisdictions, operators have achieved significant cost savings by compacting containers prior to transport. There may be an opportunity for Encorp to save on program costs by improving efficiencies, potentially leading to reduced CRFs for consumers.

Interplay between programs

With beverage containers recycled in B.C. at an impressive 84 percent rate, the province is addressing the rest of the packaging stream. May 2014 marked the implementation of a program for recycling residential packaging and printed paper (PPP). The packaging component includes a wide range of materials, including cardboard boxes, plastic milk jugs, steel aerosol cans and more. With the addition of the new PPP recovery system, the province can expect to build on the success of its beverage container recycling program and increase the recycling rates of other types of materials.

Some people in the province are suggesting that the beverage container deposit program be eliminated, with beverage containers instead folded into the multi-material program. However, CRI recommends against moving to a one-bin collection system of multiple products and material types, because that type of change would reduce beverage-container-specific recycling benefits. Such advantages – very high reuse and superior redemption rates, collection of high-quality materials and significant litter reduction – primarily are exclusive functions of the beverage container program achieved by keeping it separate from multi-material recycling. Experience has shown that combining the two programs does not produce any significant gains in collection efficiencies, volumes or cost savings.

Throughout North America and Europe, jurisdictions that use both beverage container deposit and multi-material collection programs have the highest recovery rates of high-quality packaging materials.

By keeping its beverage container recycling program separate, and addressing the concerns CRI identified about its operation, B.C. can move forward on the path toward maximizing collection of packaging and printed paper – while maintaining its impressive worldwide leadership in beverage container recycling and reuse.

Susan V. Collins is president of the nonprofit Container Recycling Institute (CRI), a leading authority on the economic and environmental impacts of used beverage containers and other consumer product packaging. Its mission is to make North America a global model for the collection and quality recycling of packaging materials. She can be reached at [email protected].