A small Midwest town is slated to welcome a plastics-to-fuel facility converting up to 100,000 tons of mixed plastics per year into gasoline and diesel fuels.

Renewable Energy Solutions (RES) Polyflow in late December announced Ashley, Ind., population 1,000, as the location of its first commercial-scale facility, which will cost roughly $90 million to construct. Once complete, the facility will use a patented plastics-to-fuel technology to convert mixed plastics that would otherwise be destined for the landfill into gasoline and diesel blendstock.

“We can have a varying incoming plastic stream and still make a reliable hydrocarbon product,” Jay Schabel, CEO of RES Polyflow, told Plastics Recycling Update: Technology Edition.

RES Polyflow is a founding member of the Plastics-to-Fuel & Petrochemistry Alliance, which was started by the American Chemistry Council.

To date, about 65 percent of financing for the Indiana operation has come from angel equity and the remainder from debt and grants, Schabel said.

He added the full $90 million has not yet been raised.

Construction is scheduled to begin in the second quarter of 2016, and the plant is slated to come on-line in mid-2017, with full production expected in late 2017.

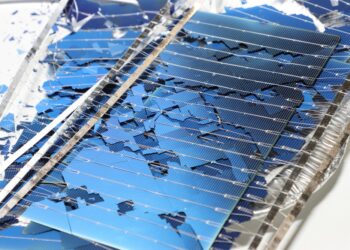

Range of resins targeted

The facility will be capable of converting 100,000 tons of mixed plastics into 17 million gallons of fuel blendstock, or roughly 12 pounds of plastic per gallon.

While LDPE is probably the most common resin it will see, RES Polyflow expects to also see PVC, PP and PS. RES Polyflow will work to limit PVC to about 3 percent to 4 percent of the supply stream, however, because up to half of it is chlorine, which isn’t a hydrocarbon and reduces the fuel yield.

Schabel sees the technology as complementary to PET and HDPE recycling, not in competition with it, he said.

Plastic films may tangle equipment at recycling facilities but they are a great feedstock for RES Polyflow’s technology, he said. The facility will also be able to recover metals for recycling, including wire from tires.

By weight, 3 percent to 12 percent of the incoming loads is expected to be filler material RES Polyflow won’t be able to convert to hydrogen or carbon.

This material includes glass, clay and talc.

Materials sourcing

RES Polyflow will pay to deliver post-consumer and post-industrial mixed plastics to the northeast Indiana facility from a radius of 10 to 150 miles, Schabel said, although it could come from farther away locales if material is densified.

“It’ll divert a lot of material away from landfill,” he said. “That’s the beautiful part.”

The Perry, Ohio-based company expects about 60 percent of the incoming stream to be sourced from large manufacturers currently recovering fiber and metals but landfilling plastics, with the remainder coming from post-consumer reclaimers landfilling the material, Schabel said.

RES Polyflow has signed up 15 suppliers for the planned Ashley facility. Using a small demonstration plant in Ohio, the company is testing the suppliers’ plastics to determine fuel yields, which will help determine the prices it pays for scrap.

RES Polyflow anticipates paying $20 to $40 per ton for material, with prices indexed to what RES Polyflow can get for its fuel blendstock.

For recycling companies currently landfilling plastics Nos. 3-7, the technology could turn a cost item into a profit item, Schabel said.

He also said he’s found that the long-term 10-year agreements RES Polyflow is seeking are unfamiliar to many plastic scrap suppliers.

“I think it is a paradigm shift,” he said. “People have to realize the world’s changing on waste-to-value, and long-term relationships are going to be valuable.”

Schabel also said he isn’t worried about the effects of low oil prices on the project’s viability.

The project “still makes strong financial sense at today’s prices,” without any government subsidies, he said.