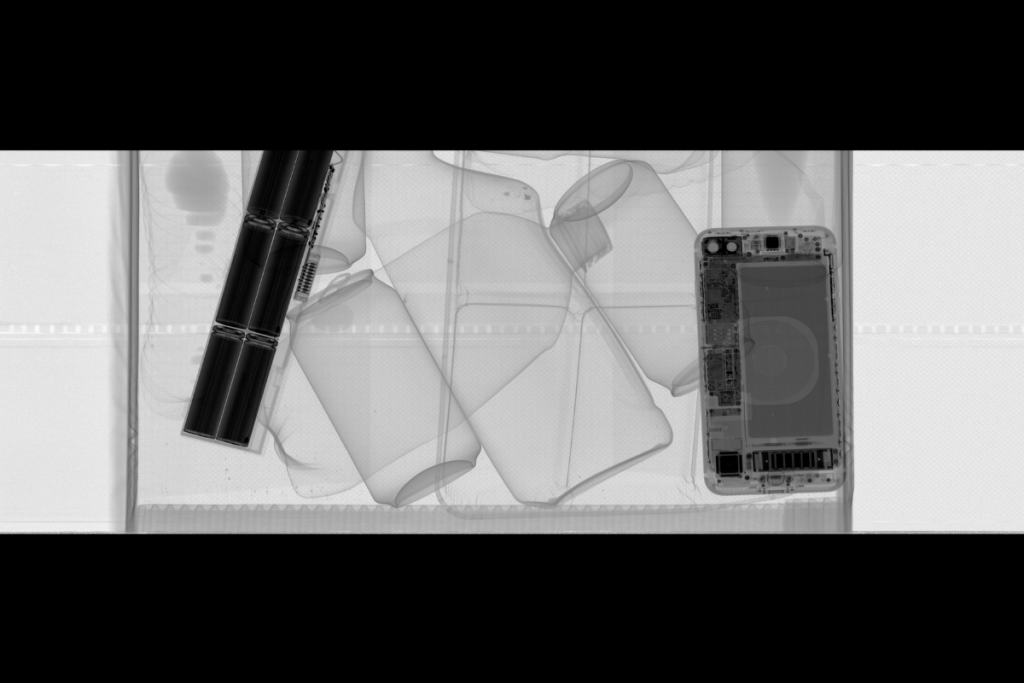

Battery-bearing devices are detected in the municipal recycling stream using X-ray imaging. | Courtesy of Battery Detection Solutions

An emerging equipment supplier uses an advanced type of X-ray imaging to locate batteries in recycling facilities while also aiming to capture data on the overall composition of commodities in the stream.

“You’re not just taking one X-ray picture, you’re taking, like, eight at once across the energy spectrum,” said Rich Cisek, founder and CEO of Battery Detection Solutions, describing multi-spectral imaging. “The ability to do that in an automated way is what allows this whole thing to work.”

Cisek says his goal was to go beyond a traditional X-ray machine, which shows certain materials as darker or lighter depending on their density, by having the equipment also indicate what the subject item is made of.

Battery Detection Solutions is one of several companies that uses X-ray technology to identify and sort batteries. Cisek and Jason Nielsen, the company’s vice president of customer solutions, discussed the technology and its applications in an interview with E-Scrap News.

Facility placement and purity potential

The Arizona-headquartered company, which launched this year, currently offers several designs based on customer application.

In the municipal recycling world of materials recovery facilities, or MRFs, Cisek says the equipment could be placed on top of the infeed conveyor at the beginning of the sorting process, where it would aim down at the materials moving past. The company produces equipment up to 60 inches wide, sized to customer needs, with the ability to look into a stream that’s 40 inches in depth.

If the goal is to identify batteries, he says it could be positioned before the material reaches that step.

“The better opportunity is, as soon as the truck is unloaded, to put the material through the x-ray, so that you know there are no latent batteries waiting in your pile to burn up,” he said.

The company is also experimenting with truck-mounted X-ray technology. The goal would be to inspect curbside carts as they’re being picked up, and if a battery’s detected, the cart can be left at the curb. That’s “a little trickier,” Cisek acknowledged, but the company is looking at those possibilities as it tries to move as far upstream as possible.

“The only way to eliminate the chance of a fire is to make sure the batteries can’t get in” a facility in the first place, Cisek said. “Once you start sorting things, you risk damaging a battery.”

Additionally, although the company’s name indicates a focus on battery detection, it’s also framing its technology as a way to validate stream purity. Cisek suggested it could be used to evaluate inbound loads of circuit boards in an electronics recycling facility to verify their grade and how much gold they contain.

For commodity verification in the municipal recycling world, Cisek suggested the imaging equipment could be placed on the back end of a sorting line. He offered the example of the X-ray analyzing the fiber stream in a MRF as the material is going into a baler.

“That’s a big differentiator to be able to tell whoever’s buying it, ‘We know it’s 100% pure,'” Cisek said.

Cisek reiterated the technology his company uses has its roots in the food inspection world, where “the standard for accuracy is immensely high.” The recycling industry has laxer standards for quality, so the company can dial back the purity inspections to some extent, producing less expensive equipment while still providing adequate inspection. Cisek estimated his equipment can provide material discrimination “for within 1-2% of what’s in there.”

Recycling application came from a chance meeting

About five years ago, Cisek, an electrical engineer who was working in the food safety inspection field, began thinking about bringing artificial intelligence into the inspection technology he was developing. Combining AI with other advancements in sensor equipment could significantly increase automation in the inspection field, he thought.

Cisek ended up developing such technology at a company in the food inspection space. After that success, he was talking with venture capital firms about what the next step would be to commercialize the technology in other spaces.

As luck would have it, Cisek was flying back from a meeting in Chicago last fall and happened to notice the person seated next to him on the plane was looking at different inspection technologies on the internet. Cisek recognized some of the equipment.

Cisek struck up a conversation and asked what his seat neighbor was looking for in that equipment. As it happens, his neighbor was on the flight back home from a recycling industry conference.

“And he’s like, ‘Oh man, the recycling industry, we have some real challenges that we don’t really have a handle on,'” Cisek recalled.

From that initial spark, then learning about the battery fires plaguing many sectors of the recycling industry, Cisek began assembling a team that has become Battery Detection Solutions. The company got organized in April of this year, and the team began building prototypes.

Cisek says the proliferation of these battery chemistries indicates the scale of the problem, which only emerged as a major recycling industry challenge six or seven years ago. In some ways, the lithium-ion battery challenge mirrors the CRT dilemma, where regulation lagged behind the mounting volume of problem materials in the waste stream, creating a sector-wide crisis.

“You look at the penetration of consumer goods with lithium-ion – it’s billions, it’s billions,” Cisek said. “And so even if some magic battery comes out tomorrow where people are like, ‘Hey, look, it doesn’t catch on fire anymore when you shred it,’ we’re still going to have a decade and a half of risk around the stuff.”