Two e-scrap collectors that allegedly sent cathode ray tube glass to failed Midwest processor Recycletronics recently received demand letters from the U.S. EPA seeking compensation for more than $1.3 million in cleanup costs from Superfund remediation activities in 2022.

Dynamic Lifecycle Innovations and nationwide hauler WM, formerly Waste Management, in mid-April were contacted by the EPA’s Region 7 office, related to CRT materials that the companies sent to Sioux City, Iowa-headquartered Recycletronics a decade ago.

The demand focuses on just one of at least six locations where Recycletronics, led by former CEO Aaron Rochester, left abandoned CRTs, CRT glass and other e-scrap materials. In a statement, EPA spokesperson Kellen Ashford confirmed the agency is involved in cost recovery efforts through the Superfund program. Under that process, cleanup cost liability is not limited to site operators but may extend out to companies that arranged for transport of materials to the site, Ashford noted.

“The removal action consisted of removal of approximately 1,431 gaylord boxes of CRT-containing glass, some of which were labeled with Dynamic’s name and some of which were labeled with Waste Management’s name,” EPA said in an overview of the cleanup.

EPA is seeking $1.32 million in cost recovery, Ashford said. The agency declined to provide further comments on the status of the cost recovery, citing a policy against discussing ongoing litigation.

Located in Akron, Iowa, the rural property is so far the only Recycletronics cleanup for which the EPA is initiating cost recovery proceedings, although the agency in 2022 also funded cleanup of at least one additional Recycletronics site, a location in South Sioux City, Nebraska. Ashford noted the two EPA-funded cleanup sites have different potentially responsible parties – the agency term for suppliers that could be liable – “due to the nature of shipping and receiving wastes at the two sites.” It was not immediately clear by press time whether EPA will seek cost recovery for the Nebraska stockpile cleanup, which had estimated cleanup costs of $1.4 million.

In a statement, Dynamic Lifecycle Innovations noted that the Superfund law — officially the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, or CERCLA — uses “broad language that can assign liability regardless of a company’s direct intent or involvement. In this case, our company is being included only as a result of the statute’s scope, and not because of any deliberate or negligent action.”

Dynamic’s statement added that the company maintained R2 certification during the time the CRT glass was managed, and that it conducted internal audits, end-to-end material tracking and third-party audits to verify its downstream vendors.

“Dynamic had no knowledge of this Recycletronics site, or that any material we handled was being directed there,” the company added. “It was never disclosed to us, nor did it appear in any audit records or due diligence documentation.”

WM did not respond to requests for comment on the demand letter.

The Recycletronics supplier cost recovery demand is the latest example of e-scrap processors facing cleanup cost responsibility for CRTs they sent failed processors many years ago. It follows the extensive Closed Loop Recovery & Refining supplier lawsuit, which targeted dozens of e-scrap companies for massive CRT stockpile cleanups in Arizona and Ohio.

Liability headache spans a decade or more

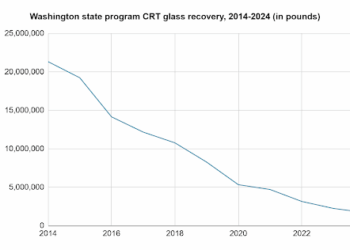

Recycletronics operated a half-dozen sites across Iowa and Nebraska, but the company drew the attention of state regulators in 2017 for its failure to move CRT glass and resulting stockpiles. Nebraska state records indicated the company at one time used Closed Loop as a CRT downstream, suggesting Closed Loop’s collapse could have factored into Recycletronics’ challenges.

State and federal regulators later in 2017 conducted enforcement actions against the company for illegally storing an estimated 16.9 million pounds of CRT glass and intact CRT devices across at least six locations, including four in Iowa and two in Nebraska.

By 2018, Iowa’s attorney general had sued the company for its illegal e-scrap storage, seeking to compel it to clean up its sites. Later that year, company owner Aaron Rochester, a former Sioux City Councilor and member of the city’s environmental advisory board, was hit with criminal charges for illegally storing and transporting hazardous waste.

Rochester pleaded guilty in 2021 and was sentenced to three years probation later that year.

Then the cleanup activities began. Rochester repeatedly provided evidence that he lacked the financial ability to fund cleanup activities, according to EPA records. In 2021, the U.S. EPA issued a memo indicating that at least two of the Iowa sites were cleaned up at the expense of the property owners. One of those was BNSF Railway Company, which had acquired a former Recycletronics site as far back as 2014. After EPA inspections in 2017, BNSF learned it was liable for cleaning up 2 million pounds of CRT glass Recycletronics had left on the property.

The EPA also indicated a third Iowa location was owned by a property owner that the agency believed had “some financial resources and alternative options to manage the type of waste stored at that location.” EPA had previously noted that Recycletronics leased one of its Iowa sites from WM and that WM came to an agreement with EPA to clean up 768,000 pounds of CRT materials at the leased site.

That left one Iowa site, the Akron facility that EPA began cleaning up under the Superfund law. The location is a facility surrounded by farmland owned by a private landlord without the resources to facilitate a cleanup of the site, according to EPA documents.

Rochester had leased the property, ultimately amassing a substantial CRT glass stockpile before the business failed.

“The business would hold public collection events, extract the components that had value, and then started compiling the leaded glass from the cathode ray tubes,” EPA wrote of Recycletronics’ general business model. “A legitimate recycler would need to pay to send the leaded glass off for proper disposal. Instead, Aaron Rochester began storing the leaded glass in various warehouses rented throughout Sioux City, Iowa and South Sioux City, Nebraska.”

The Akron landlord purchased the site when it was already leased to Rochester, and Rochester soon stopped making payments on the property, according to the EPA, leaving the property owner “stuck with a building full of leaded glass.”

“The leaded glass is stored in cardboard Gaylord boxes stacked two and three high throughout the building,” the agency wrote in 2021. “There is no space to walk between the boxes and the boxes are packed tightly. The building is filled from wall to wall.”

EPA removed 1.9 million pounds of material from the facility from March through September 2022, transporting it to a landfill permitted to dispose of such hazardous waste.