A recently published survey of e-scrap companies in the U.S. and abroad offered a look at how many operators are handling plastics recovered from devices. It also provided insights on why a domestic e-plastics processing industry has yet to develop.

Sustainable Electronics Recycling International in February published the report, which involved a survey of 370 electronics and plastics processors, brokers and other e-scrap stakeholders.

The survey received 55 responses over two and a half weeks representing 214 facilities worldwide. Although the report acknowledges the findings aren’t statistically significant, it maintains the results are “suggestive of general trends for the management of plastics from electronics.”

The report found a range of e-plastics management practices but also a sorely lacking U.S. e-plastics processing sector, broadly speaking.

“With the option of Asian recycling markets for plastics remaining largely available from a U.S. trade perspective, little incentive is being created to invest in e-plastics separation capacity and capability,” stated the report, which was commissioned by SERI and completed by consulting firm 4R Sustainability.

On a hopeful note, the report drew a parallel with how the U.S. paper and plastics recycling industries shifted after China banned imports of most recovered paper and plastics. Long the primary downstream outlet for these U.S. streams, China’s decision forced substantial domestic investment and a restructuring of the U.S. paper and plastics recycling system. Now far more of those U.S.-generated recyclables remain in the country.

“If a similar disruption were to occur for e-plastics, could the same focus and investment occur to create new processing solutions that would create quality grades of plastic material that would be eligible for export to support electronics manufacturing in Asia?” the report probed.

Such a disruption is underway – indeed, it was the impetus for the report. The 2019 Basel Convention changes that altered how scrap plastic can be traded globally have added new regulations to e-plastics shipments between countries. And given the U.S.’s status as a non-party to the Basel Convention, the new regulations are technically a ban on exporting material from the U.S. to Basel-party countries.

Despite that, material continues to flow overseas because e-scrap firms lack robust alternatives, as E-Scrap News has reported and certification groups including SERI and e-Stewards have noted.

In presenting the report, SERI said the Basel changes – and overall confusion around compliance – were a key driver for the report.

“SERI and R2 did not usher in these regulatory changes, but we want to help inform approaches that the whole value chain can pursue to help the electronics recycling industry navigate them,” SERI wrote.

The organization is accepting comments on the report through April 30. SERI says it will compile “constructive feedback anonymously into an appendix,” which will be published on the organization’s website.

Typical e-plastics management

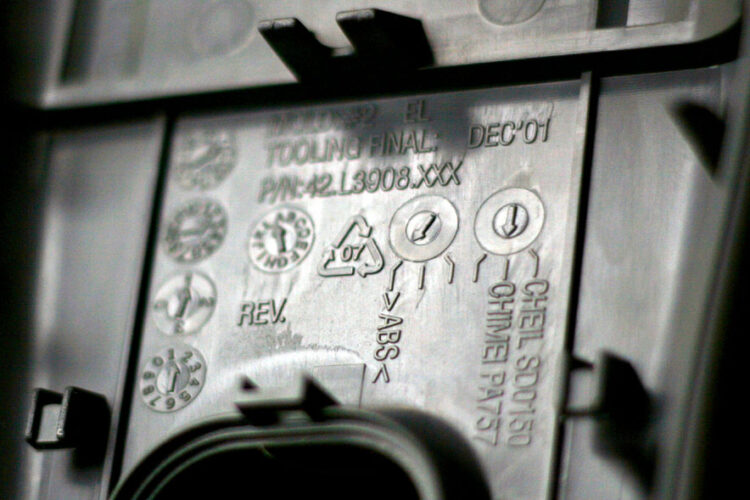

The report provides a picture of how several e-scrap companies handle e-plastics. About half of respondents said they use more than one preparation method to process e-plastics on-site. Of those, most said they manually dismantle plastics from devices and either bale or shred the plastics. A handful of respondents reported whole-unit shredding without any manual disassembly was their primary processing method.

Of the companies that said they did some amount of onsite separation of plastics from devices, many reported doing some additional sorting of plastics before sending them to a downstream. That included separation by either color or density, with the most common color sort being black or colored material separated from white plastic, and the density sorts typically producing blended streams of PE/PP and ABS/PS.

Only a few of these e-scrap companies were operating in North America – most e-plastics separation is occurring in Asia, SERI noted.

“In the U.S., plastics separation was heavily influenced by the capacity of the electronics recycling operation,” the report stated. “As in, if the company was smaller-scale and using vocational workers, manual separation was more common than shredding whole devices, which happens more frequently at larger-scale facilities. Manually dismantling devices is a slower process but can create high-quality streams customized to the buyers’ specifications.”

Some U.S. companies are recovering the ABS from e-plastics streams and disposing of the rest, the report noted.

Without significant sorting capacity in the U.S., most respondents unsurprisingly reported selling e-plastics in some sort of mixture. Sometimes they are sold as a stream sorted by the type of product the plastic was recovered from, sorted by color, shredded and mixed together, or baled and unsorted. Only 20% of respondents reported selling a separated, shredded stream of e-plastics.

Respondents further offered a disheartening view of the future of U.S. e-plastics recovery.

“Of the U.S.-based electronics recyclers interviewed, the outlook for e-plastics in the U.S. was not positive,” SERI noted. “Most reported struggling to consistently move plastics from electronics. All electronics recyclers interviewed have explored the option of adding additional sortation capabilities for plastics but deemed the investments too risky. A lack of market certainty, potential regulatory changes and the risk of sustained, low virgin resin pricing were all seen as deterrents to integrating plastics separation onsite.”

As for downstream markets for those various sorted and unsorted streams, many respondents reported using multiple outlets. The majority, 70%, said they send e-plastics to plastics recycling companies; 36% said they send the material to another electronics recycling company for further separation; 31% used a broker; 33% sent the material directly to market for remanufacturing, a business practice largely confined to Asia; 32% used an incinerator or cement kiln; and 11% sent the plastics directly to landfill.

“No recycler reported landfill or incineration as their exclusive method of managing e-plastics,” the report found. “Energy recovery seems to be preferred over landfill and that may be a reflection of zero landfill policies that are in place.”

Additional industry challenges for e-plastics

Beyond Basel, SERI noted a number of factors creating a tough environment for e-plastics processing, as reported by respondent recycling companies. The challenges include:

- “Highly volatile pricing” for e-plastics, particularly the difference between what Asian downstreams will pay and what U.S. buyers will pay.

- Design choices by OEMs that make e-plastics recovery challenging, such as unclear communication over which resins are included in products, the use of additives that can trigger additional regulations on e-plastics, and the lack of recycled content included in plastic used in new electronics that is a missed opportunity to create a market for recycled e-plastics.

- A lack of consistent, reputable end markets, largely due to quality specifications required by buyers.

- Pricing competition between virgin and recycled resin, specifically the low cost of virgin resin that has the effect of lowering demand for recycled resin and therefore stymying greater interest in investing in e-plastics processing technologies in the U.S.