This article originally appeared in the Winter 2019-2020 issue of E-Scrap News. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

For many operators in the world of electronics recycling, plastics have recently become a major talking point.

Before 2017, the scrap plastics that were pulled off recovered TVs, computers and other devices were either baled or shredded and moved to brokers or other shippers that found a home for the material in China. Prices paid for this typically mixed, engineered-plastic material were modest, but electronics recyclers knew the loads would move and their costs would be covered.

Not surprisingly, China’s National Sword policy shifted the e-plastics landscape significantly, forcing e-scrap companies to hold onto material, pay to dispose of it or search desperately for new outlets.

However, e-scrap sources now say some stability is returning to the market.

Asia remains the destination for many plastics recovered from electronics. And electronics recycling companies and brokers say they’re currently able to move the material, though extra work is now required.

“Our labor cost definitely is higher, but in today’s market, the plastic recyclers are in a shortage of high-quality, cleaned plastics – we command a better price,” said Jade Lee, president and CEO of Lombard, Ill.-headquartered Supply-Chain Services, Inc., a company that does a significant amount of sorting before shipping e-plastics. “It’s still not at the level of before China’s ban on importation, but it’s much better than 2017 and 2018.”

Activity focused in Asia

For Far West Recycling in Tualatin, Ore., prices for recycled e-plastics are fluctuating and end markets are quickly shifting, which can be challenging. But the company is still finding buyers, said Jeff Steinfeld, director of sales at Far West Recycling.

Far West brokers a lot of e-plastics, mostly handling black and white CRT plastic, shredded LCD plastics and other shredded materials.

Although China is out as a destination for the material, Far West still predominantly works with Asia, selling shredded plastic to ISO-certified facilities in various countries across the continent.

Meanwhile, Jeff Gloyd, vice president of sales and marketing for nationwide e-scrap processor URT, said today’s most robust e-plastics markets are centered on Hong Kong and other areas in Asia. Movement has been about the same for the past six months, he noted.

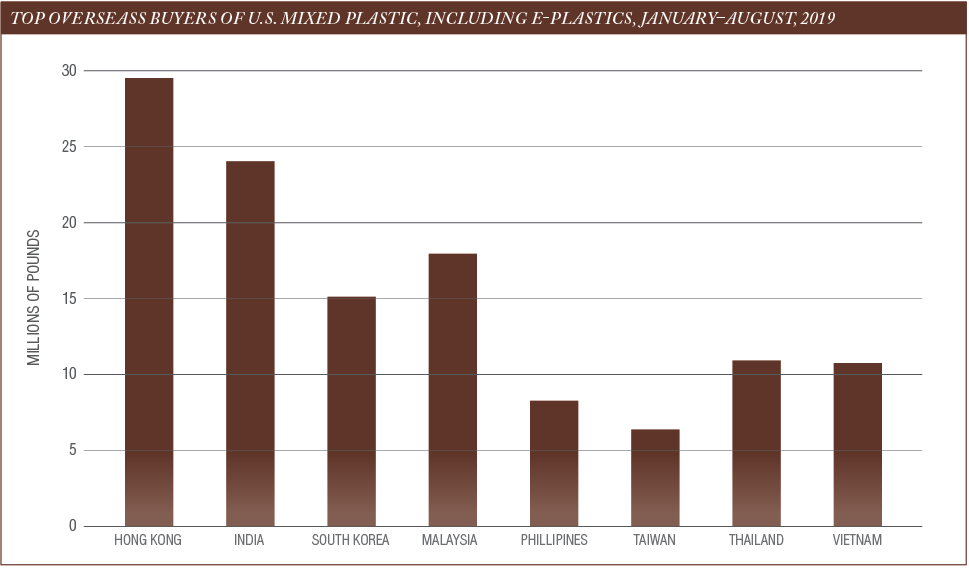

Trade figures for mixed plastics (a category that includes e-plastics as well as a variety of other polymer types) give a rough idea of where U.S. e-plastics and other low-value plastics are being sold.

From January through August of this year, the largest Asian buyers of these materials were (from largest to smallest volume) Hong Kong, India, Malaysia, South Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, the Philippines and Taiwan (see chart below).

Size is an advantage

The executives from URT and Far West point to the volume of material they handle as a component of their ability to keep moving e-plastic.

Far West handles a substantial amount of plastic from municipal recycling programs as well as e-scrap materials, so the company has dedicated plastic brokers on staff. “There’s a volume,” Steinfeld said.

The company also works with suppliers that are already generating sorted and shredded e-plastics. For smaller scrap handlers, problems can stem from a lack of mass, leading to a lesser quality product and quickly falling prices.

“If you can’t make weight in a container, if you mix them, tear apart computers and TVs and throw it into the same bale, the price is going to be significantly impacted,” Steinfeld said.

Similarly, Gloyd pointed to URT’s size as a key factor in the company’s ability to continue moving e-plastic with limited disruption. The company has been able to maintain relationships with recycled plastic buyers who moved their equipment out of China due to the recent import restrictions and have relocated to different points in Southeast Asia.

Gloyd added that URT has heard from several smaller processors who are struggling to move e-plastic and are interested in sending the material to URT. Although the company accepts e-scrap from other processors in some cases, the company is cautious when it comes to plastics.

“The downstream is so limited and volatile, that if something happened to it, we’re stuck with … loads of material from other vendors sitting on our floor,” Gloyd noted.

‘They still have to ship it back to China’

When China shut the door to virtually all scrap plastics at the beginning of 2018, the impact on Chinese recycling companies was profound.

“Plastic processors reacted very quickly, moving their operations to Southeast Asian countries,” Lee said. Because of that shift, companies are facing higher costs to process e-plastics. They have to hire sorting experts, the labor market is different in Southeast Asia compared with China, and shipping costs are a lot higher, Lee explained.

Although China has stopped importing scrap plastic, the country remains the downstream location for the vast majority of recycled plastic pellets that are being produced by recyclers who have moved to Southeast Asia, according to Lee.

“Everything they process is still going back to China in the pellet format, because all the compounders are located in China,” she said (compounding is the process of mixing a base plastic material with additives). “In Southeast Asian countries, the market is very small, so they still have to ship it back to China at additional cost to them as well.”

In addition, many buyers will not accept the volumes of shredded e-plastic that used to move to China, and the material they do take fetches very low prices.

That’s because of the yield loss when processing: When shredded plastic is put through the first wash and separation process, between 30% and 40% of the load might end up being disposed, Lee said.

And even after that yield loss, the resulting pellets will only have uses in low-grade manufacturing applications, she added. The plastic would almost certainly not be able to be used in manufacturing new electronics, she said.

For baled e-plastics that have had some initial sorting by color, there is far less yield loss, and recycling companies can generate pellets with 99% purity, Lee said. These are shipped to China, where they are used in toys, automotive plastics, electronics and more.

It’s also important to note that many countries in Southeast Asia have enacted stringent import restrictions of their own following China’s decision, meaning it can be hard for recyclers in Southeast Asia to source scrap plastic feedstock that will clear customs. Shredded mixed e-plastics can be rejected at the borders due to quality concerns.

Nevertheless, URT has seen a slight uptick in the value of e-plastics recently, Gloyd said. He attributes that fact to increasing demand for the pellets Southeast Asian companies are producing for buyers in China.

Domestic future?

URT sells a mix of shredded and baled e-plastic. Gloyd agreed that baled materials often fetch greater values because it’s easier for downstream processors to sort out specific resins than with shredded plastic.

Gloyd also noted that if a U.S. company were to take steps to sort e-plastics into specific resin streams, the markets would open up substantially. For example, if an operator can create a fairly clean ABS stream, “there are markets all over the world for that material,” Gloyd said.

And in fact a number of domestic processors are reportedly exploring the possibility of bolstering their sorting capabilities.

But Gloyd added it’s not as simple as installing new equipment and improving the product. That takes capital and floor space, but more importantly, it stakes a lot on an uncertain market.

“You spend all kinds of money on upgrading systems to do more, and then all of a sudden something opens up in China again or somewhere in Southeast Asia, and it becomes obsolete domestically,” Gloyd said. “I think companies in our position kind of tread lightly in those waters.”

Lee, whose firm sorts and bales before shipping material to Asia, also works directly with many electronics manufacturers to help them meet the recycling quotas they’re required to hit under some state e-scrap laws. Because of those relationships, Lee’s operation has access to design information that helps the company identify the best way to disassemble devices and remove major contaminants.

As for domestic processing of e-plastics on a wider scale, Lee doesn’t see a bright future in that sector. She said entire manufacturing supply chains would need to shift for domestic ventures to pencil out.

“The majority of compounders are in China, so you’d have to ship all the pellets over there,” she said. “The compounder sells it to a parts manufacturer; the parts manufacturers are all in China.”

Parts companies then sell to assembly plants, which are also concentrated in China.

“So if I set up a plant here, I can’t compete,” Lee said.

Colin Staub is the staff writer for E-Scrap News and can be contacted at [email protected].