This article originally appeared in the Fall 2018 issue of E-Scrap News. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

Over the past 20 years, e-scrap regulations that put the onus on manufacturers to finance takeback and recycling have taken shape in Europe, North America and other industrialized countries. Policymakers designed these extended producer responsibility (EPR) frameworks to reflect their governments’ enforcement capacities, and in many cases, the programs helped foster regional collection and recycling systems for electronics.

In recent years, countries with emerging economies have also begun discussing and adopting EPR legislation to manage their own tonnages of end-of-life electronics, material resulting from (sometimes illegal) imports as well as from the consumerist middle class populations that have grown in some of these regions.

However, it’s becoming clear that EPR regulations don’t always travel well. In many instances, emerging economies have different resources and capacity among their regulatory institutions, a fact that renders enforcement of legislation difficult. In addition, a large informal sector usually dominates e-scrap management in many of the countries that are now considering EPR, and frameworks adapted from the European or North American contexts are usually silent on how to engage informal workers.

In many ways, India provides the perfect testbed for evaluating the effectiveness of EPR-based legislation in an emerging economy. It has a huge informal sector that refurbishes and recycles 95 percent of the country’s e-waste, according to recent estimates. It also has a growing middle class (among its 1.3 billion residents) that is purchasing and replacing products at a more rapid clip.

Furthermore, illegal importation of electronic material adds to the amount of e-scrap processed in India, and the country lacks sufficient infrastructure to process and extract precious metals from used electronics. Finally, India’s central and state regulatory structures lack capabilities for enforcement.

In 2016, India ushered in an EPR system through a revision to its E-Waste Rules. I visited the country in 2017 and 2018 and engaged with a variety of stakeholders to understand the successes and challenges that have been seen as the process unfolds.

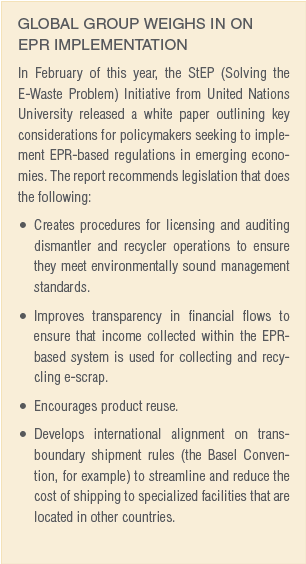

Based on those on-the-ground observations, it became clear that there are seven steps policymakers will want to consider when creating EPR-based regulations for managing electronic material in emerging economies. Some of these recommendations dovetail with points made by the UN’s StEP program earlier this year (see sidebar below).

Vikash Rajput (center) leads outreach to informal aggregators in Delhi markets on behalf of producer responsibility organization Karo Sambhav. The group has found success working slowly to build up the trust of individuals in the informal sector.

If India can find ways to manage e-waste successfully via an EPR-based approach, many of its lessons can likely transfer to other emerging economies that bear similar characteristics, albeit on a smaller scale.

1. Design legislation that accounts for weaker regulatory and enforcement systems.

Despite India being far into the implementation stage of its EPR framework, certain state regulators still lack awareness and understanding of technical requirements. For instance, India’s state Pollution Control Boards (regional regulatory bodies tasked with monitoring and enforcing the E-Waste Rules) continue to approve registrations for dismantlers that do not reflect those operators’ actual processing capacities.

The regulatory struggles were a key concern expressed by numerous stakeholders, including manufacturers, multilateral institutions and producer responsibility organizations (PROs), which are third-party entities that manage collection and recycling contracting on behalf of producers. Representatives from those entities told me the lack of enforcement capacity and a lack of clarity on operating requirements for different market actors has resulted in formal aggregators and dismantlers diverting material to harmful informal recycling either unnoticed or unpunished.

Another regulatory shortcoming came in May of this year when the Central Pollution Control Board, India’s federal regulatory body, issued guidelines for PROs that lacked specificity or rigor. This action created opportunities to approve non-qualified actors to participate in e-scrap management, potentially creating more problems in unsound processing.

It’s true that in India, policymakers often fine-tune regulations after they take effect. But, nevertheless, in that country and others, it would be wise to develop clear roles for central and state local government officials and robust criteria for registering dismantlers before EPR legislation is finalized.

2. Build in transparency of material flows to hold stakeholders accountable.

In 2018, newly established PROs in India working on behalf of producers to achieve collection and recycling targets found that formal, registered recyclers were re-selling e-scrap back into the informal sector in lieu of recycling it. Some formal recyclers had also been “processing” the same pile of material multiple times, allocating it to different producer clients. In both scenarios, formal recyclers generated false certificates of destruction (one PRO unearthed some of these findings after hearing feedback from informal workers who recognized their re-purchased material).

Though limiting corruption presents ongoing challenges in weak regulatory environments, it is vital to require documentation that tracks both financial and mass balance flows of designated amounts of material. In addition, all producers should report into a single tracking system. These steps would improve traceability and make it more difficult for actors to game the system because the protocols detect double counting.

3. Create realistic pathways to engage informal workers.

Policymakers today in both industrialized and developing countries recognize the need to engage informal workers in collecting, aggregating and dismantling electronics, given informal actors’ significant role in managing most of the e-scrap in emerging economies.

But finding ways to effectively bring the informal sector into an EPR system is an enormously complex challenge.

An informal collector uses an electric rickshaw to collect e-scrap from local repair shops in Patna, India.

Over the past decade, India has seen several multilaterally funded pilot initiatives that tried to connect informal collectors to formal dismantlers and recyclers to divert material away from unsafe informal processing. In general, the projects found that informal metals processors could offer informal collectors and dismantlers higher prices than formal recyclers could, a dynamic that continues to this day. In addition, material that does go to the formal sector is often first cherry-picked for high value components, and subsidies to formal recyclers, as part of pilot initiatives, proved unsustainable.

However, there are examples that point to encouraging possibilities when it comes to engaging informal actors.

In late 2017, one PRO in India, Karo Sambhav, began experimenting with ways to engage informal workers by targeting lower level aggregators. The group provided these individuals with new skills, trustworthy financial transactions and access to a digital economy by helping them set up bank accounts and tax identification.

The Karo Sambhav process of working with these individuals was well-planned and took into account the various intricacies of India’s informal e-scrap economy. For instance, the group found that it needed to start by focusing on smaller aggregators in the Delhi area because these were the people that actually needed help finding ways to operate more efficiently and were open to new ways of doing business.

Karo Sambhav staff spent time building up the trust of these traders before trying to work with them to make bigger shifts in their processes. This patience paid off, with a number of aggregators transitioning to digital bank accounts and developing new skills that could be applied to other areas of life.

The key to bringing informal players into the fold of an EPR framework is meeting those individuals on their terms and working slowly to show them the practical benefits of any procedural shift.

4. Ensure PCBs can be exported and/or establish greater domestic metals management capacity.

In India, the majority of government-registered recyclers are dismantlers with no capabilities to extract precious metals. Three known recyclers in India have claimed to extract the gold, palladium and other metals from printed circuit boards (PCBs) or other materials. However, one of these operations has since closed its Indian facilities and one has demonstrated only small-scale batch metals processing capabilities.

At the same time, several Indian recyclers export material to Umicore’s facility in Hoboken, Belgium. But starting in late 2017, Umicore relayed that recyclers experienced difficulty accessing the government-issued documents necessary to export material to the site (since India is a signatory to the Basel Convention, the government must grant a waiver to allow certain e-scrap material to be exported). In spring 2018, several stakeholders also confirmed that e-scrap exports were delayed, and many surmised that the government’s interest in ensuring greater metals security motivated the new policy. Since India is a significant gold consumer, any gold-containing material from electronics could ostensibly contribute to greater metals security in the country.

Regardless of the reasons, the stay on exports to safe overseas processing facilities has created a funnel back to informal recyclers in India who extract metals under hazardous conditions.

The policy takeaway is that any EPR legislation should ensure that pathways exist for recyclers to send material overseas for safe end-of-life metals extraction. If countries wish to retain high-value materials, parallel policy (involving economic incentives and significant infrastructure investment) will be needed to create local and regional processing capacity so that formal dismantlers have a domestic outlet for metals-bearing material.

5. Create plans for educational outreach and program measurement.

In India, under the current rules, producers are required to help build awareness of electronics recycling throughout society. However, no metrics currently exist to hold producers accountable. Several recent reports found producers negligent in their outreach efforts. Some only provide minimal information on e-scrap collection on their websites, and customer service is nonexistent or lacking among those citing collection points.

When it comes to institutions and enterprises, many own their IT equipment and are accustomed to selling it at end-of-life, often to informal collectors. So it is not common business practice for institutional purchasers to pay for collection and recycling services. Clearly, effective outreach is needed in this realm as well.

To be fair, developing outreach strategies is not easy for multinational manufacturers in countries such as India, where a cultural change is needed to shift expectations among producers and their customers. Building in outreach and awareness requirements with guidelines and metrics germane to different countries’ socio-cultural realities would help position producers to engage their customers in new ways. Doing so would also provide a level playing field among producers by establishing a floor to prevent laggard companies from shirking their responsibilities while tacitly rewarding leading companies for their educational and awareness-raising efforts.

6. Tie electronics recovery to wider sustainability aspirations.

Sound e-scrap management, through both reuse and recycling, has a clear connection to the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a collection of 17 global poverty reduction and environmental protection objectives. These include promotion of sustainable economic growth, productive employment, resilient infrastructure, and sustainable consumption and production patterns. Many stakeholders, including governments and electronics manufacturers, support the SDGs and frame their sustainability-related initiatives accordingly.

In India, where most used devices pass through several reuse and refurbishment channels before reaching end-of-life dismantling, current EPR regulations lack provisions for producers to count reuse as part of their collection targets. Though the recently revised E-Waste Rules provide written encouragement for reuse, producers must demonstrate collection and recycling of 10 percent of their sales by weight, building to 70 percent in ensuing years. No interim targets exist for reuse, however.

In India, where most used devices pass through several reuse and refurbishment channels before reaching end-of-life dismantling, current EPR regulations lack provisions for producers to count reuse as part of their collection targets. Though the recently revised E-Waste Rules provide written encouragement for reuse, producers must demonstrate collection and recycling of 10 percent of their sales by weight, building to 70 percent in ensuing years. No interim targets exist for reuse, however.

Including channels for documenting reuse might spark new business models among producers as part of their broader circular economy efforts. Linking e-scrap management to broader SDGs can also help push end-of-life electronics beyond the realm of compliance in the eyes of producers. Instead, stakeholders can see electronics recovery as a strategic opportunity to place the concept of materials management inside broader economic development and sustainability goals.

7. Apply systems thinking and engage other government entities to make a bigger impact.

Many e-scrap problems are not environmental, per se, but instead reflect entrenched socio-economic dynamics that foster an informal economy, limit transparency (and thereby engender corruption), and hinder progress toward formalization.

It is unlikely that e-scrap regulations on their own will overcome these dynamics. Rather, a systems approach is needed to foster the right conditions. For example, though India’s E-waste Rules do not explicitly create industrialized zones for informal workers to dismantle and process electronics more safely, several stakeholders, including the country’s Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology, have discussed and supported such a market development idea at different points in time.

Moving toward an objective such as an eco-industrial park would require buy-in from still other government ministries – those that oversee planning or zoning, for example. According to stakeholders in institutions overseeing e-scrap projects in India, such coordination has not occurred, though this might be changing. Currently, different government entities, including India’s planning commission, have expressed interest in promoting production across several industries (one example is discussion around recycling scrap from the auto, electronics and photovoltaics sectors).

Such a cross-governmental systems approach is needed when developing EPR legislation, since manufacturer-led financing of collection and recycling alone cannot remedy larger, endemic issues that stand in the way of progress.

A systems-level approach could identify the range of interventions necessary to foster market and regulatory conditions and create safer, more transparent and more robust electronics management systems. That’s a tenet that applies to frameworks in all countries across the planet.

Verena Radulovic is an independent writer and photographer who has been exploring electronics reuse and recycling in different countries. In previous editions of E-Scrap News, she has presented analysis and photo essays of the informal processing systems in India and Peru. She can be contacted at [email protected].