This story originally appeared in the June 2016 issue of E-Scrap News.

Subscribe today for access to all print content.

It’s never easy to understand what’s really happening on the ground of electronics processing sites on the other side of the planet. But the case of Ghana’s Agbogbloshie is particularly complex — and politically charged

The site, located within the Ghanaian capital city of Accra, has been documented by a range of global media outlets, and photos of burning cables and barefoot teenagers have been used to help make the case for stronger e-scrap management in the U.S. and other wealthy countries. At the same time, advocates for global trade and electronics reuse have noted those reports misunderstand the realities around informal scrap processing and make inaccurate assumptions about the origin of the material.

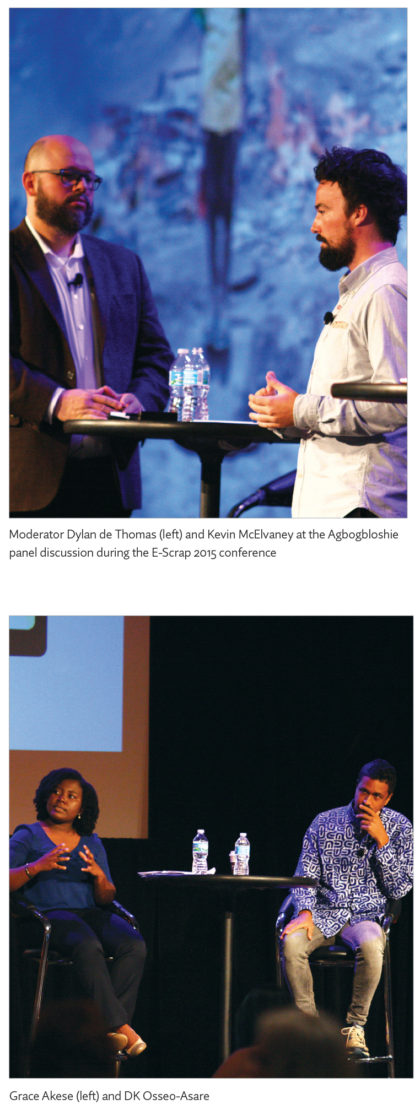

Last fall’s E-Scrap Conference aimed to help bring some clarity to the issue with a panel discussion featuring three unique Agbogbloshie perspectives.

Grace Akese is a researcher at Memorial University of Newfoundland, and her work focuses specifically on the issue of electronic waste in Ghana. Kevin McElvaney is a freelance photographer whose striking portraits of Agbogbloshie workers have appeared in The Guardian, Al Jazeera, Wired and other publications and sites. And DK Osseo-Asare is a Global TED Fellow and co-lead at the Agbogbloshie Makerspace Platform, an initiative to organize and train workers at the site.

Dylan de Thomas, editorial director of E-Scrap News and the E-Scrap Conference, moderated their discussion.

Grace, how would characterize Agbogbloshie as a whole? What kind of place are we talking about?

Grace Akese: Agbogbloshie is a general scrap yard/processing zone. That’s my perspective based on four months of research I did there in 2012 (funded by Josh Lepawsky’s Social Science and Humanities Research Council Grant). Obviously, we are aware of Agbogbloshie in relation to the issue of e-waste processing, but if you go to the site, the majority of scrap activities revolve around car waste and, increasingly, mining waste. With Ghana’s recent entry into the oil and gas production, you will also see oil barrels being processed at the site. I would estimate that about 90 percent of what gets processed there has nothing to do with e-waste. Crucially, much of the scrap goes into a micro-manufacturing industry that is also located on site. Also, if you visit the site, you will see a substantial amount of repair and re-manufacturing of electronics.

What do you mean by re-manufacturing?

Akese: For electronics, much of the re-manufacturing would be re-assembling from existing parts. When a lot of scrap gets to the site, it is mostly traded as parts that can be reused or repaired – things like motherboards, computer mice and screens. There are repair and remake shops, where you can go and give people the specifications of what you want, and they will source computer parts from their stocks and assemble for you the type of computer you want.

Kevin, can you give us your perspective?

Kevin McElvaney: I went there in September and October of 2013. My main focus was to take photos of the people. I watched them working on what you could call the burning fields of Agbogbloshie. There is this car scrap yard and right next to it is an onion market where many people go to buy their food. People in the scrap yard burn the wires, try to get copper out of different electronic devices. What I’ve seen there is they use medieval techniques. What they are searching for is material that will get them money, and you often see very young people – young, uneducated, desperate people.

DK, how would you respond to what the other speakers have said?

A photo taken by German photographer Kevin McElvaney when he visited Agbogbloshie in 2013.

DK Osseo-Asare: I think they described it fairly well. If I were to use one word to characterize Agbogbloshie, I’d say “fascinating.” I started researching for our project in 2012 and started working there in 2013. One of the clichés you hear as you pass through African cities is it seems like there is hustle-and-bustle, but it also looks like no one is really moving. But Agbogbloshie is the opposite. It’s incredibly active. The sounds you hear are full of a powerful energy. I think there are environmental problems, but the reason people go there is that there is no safety net in Ghana. The money is in the city, so people go there. There’s no affordable housing, and Agbogbloshie is a place where you can sleep on the floor of a kiosk for a very small amount of money or maybe no money. It’s instincts of survival in the city.

Kevin, you’re a photographer from Germany. What drew you to this particular site as opposed to another place in another part of the world?

McElvaney: I am from Hamburg, where there’s a big harbor, and there’s huge trade between Ghana and Hamburg. Earlier journalists had tracked containers of material to Ghana and found out they came came in an illegal way from Hamburg. I decided that if this is all true, I want to see it with my own eyes, especially as a photographer. What I’ve seen is that you have illegal trade and legal trade, but there’s a huge gray area in between where we actually don’t know what happens. I didn’t like that earlier reports just showed a poverty scene where the individuals in there are not known – you don’t know their backgrounds. I talked to the people in Agbogbloshie and tried to get an idea of why they were there. They come from the north. Often they do not know the risks they are taking while working with these materials.

Akese: It’s also important to note that when we represent Agbogbloshie as a place where e-waste goes to die, we inadvertently amplify privileged histories. The government of Ghana has for a long time struggled with settlers who have been living on the land at Agbogbloshie for over 15 years. Yes, some of the activities at the site such as cable burning are highly toxic. And something needs to be done about it. It’s not that such risks to workers don’t exist – they do – but if we put up the same representations of Agbogbloshie as the digital dumping ground over and over again, the government mobilizes these representations to further its own interest in the land at the expense of the workers. In June [of 2015], part of a slum was demolished. They were able to do it because the rest of the world says, “It’s just a place where e-waste is dumped.” But the reality is that there are Ghanaians making a legitimate living at Agbogbloshie because they are in an economy that doesn’t give them many opportunities. Most of the workers at the site are economic migrants from deprived communities in the northern part of the country.

DK, a lot of the work you’re doing is helping bring some opportunities to individuals in Agbogbloshie. Can you describe your concept?

Osseo-Asare: A lot of times what people miss is that Agbogbloshie is a node in a network. It’s not just the activities happening within the boundaries of Agbogbloshie but also its vast reach. Some of the people there are collecting scrap from as far away as [bordering nations] Ivory Coast and Burkina Faso. They are actually bringing end-of-life equipment to this site, and there is a strategic collection of components, both in electronics and the automotive side. In that sense, Agbogbloshie is a supplier. That’s where we come in with the Agbogbloshie Makerspace Platform. We say, how can we “green” some of these very crude recycling practices? But equally, how can we leverage all of the materials that are here – and, in a sense, the expertise that’s here – and transform it to a network for digital fabrication and distributed manufacturing. There’s a lot of young people in Ghana and Africa. Where are their jobs going to come in the future? We all know the future is going to be dominated by essentially robots and things that are electronic. We figure the best way to start educating a workforce is to learn from existing technology – learn how to fix things and innovate on top of that.

What specific kinds of things are you doing to try to improve crude processing practices, like the burning of material?

Osseo-Asare: We want to empower people with information. One local person built a drone partially from materials salvaged in Agbogbloshie. Part of the idea is to be able to fly around Agbogbloshie and collect pollution data. We’re also working on a digital platform to network and link people in the scrapyard with the people we call the makers, the ones doing the repair and working in these micro-manufacturing outfits. We want to try to link them and help them share information with less friction. This will help people know more about the materials in components so they know their values, but also to warn them about hazardous materials. People are there because they are looking for money, and we want to show them better practices can lead to better businesses. The Makerspace itself is a small structure we made. The steel is all from Ghana, and most of it includes metal recovered within the scrap yard of Agbogbloshie.

That is certainly one of the more optimistic takes on Agbogbloshie I’ve heard. Why then do you all think so many news organizations have portrayed Agbogbloshie as a dump? They can’t all be lying, right?

Used equipment sits in an Agbogbloshie repair shop. Photo by Grace Akese.

Akese: The pushback here is not a denial of the risk that is there and the kind of imagery you see. They are there. But if you’ve lived in Ghana and have seen the way people are constrained every day and the kind of unemployment that is there, sometimes you come to appreciate some of the work these people are doing. It’s not pretty. But these are people that need to make money and are living in slum communities. Importantly, they constitute the informal sector that has long played an important role in Ghana’s waste management. The pushback is also not a denial that some electronics, originally discarded in the West, eventually end up at Agbogbloshie. It is certain that the electronics at Agbogbloshie may at some point in time have had owners in the West, and in the East too, as Chinese-made goods of all kinds, including electronics, are now dominating African markets. The pushback is about unsubstantiated statistics and claims about the site, which seem to have traveled well with the help of photos and documentaries of ruins. The pushback is about the use of these unsubstantiated claims to drive policy direction and international trade laws in ways that can be potentially damaging not only to Agbogbloshie and Ghana but Africa as a whole.

Osseo-Asare: A lot of these journalists have never been to a scrap yard anywhere. They fly in, take a taxi from the hotel and then just walk into an environment where everyone is dismantling things and it’s dirty and chaotic. It just blows your mind because you have no reference point. Also, while I recognize we need people to research and study things, they are not necessarily the people to fix actual problems. I don’t think it’s rocket science to improve Agbogbloshie conditions. Most people in the e-scrap industry would walk in and say, “We need to order one of these types of tools and some of these and train these people to do this, and it’s done.” But the people that are coming to look have expertise in areas other than the industry. They are not the people that are the best qualified to say, “Let’s do this in a better way.”

From what you’ve seen and experienced, does it seem most of the material flowing into Agbogbloshie is coming directly from developed countries? Or is this material that has been used by consumers inside Ghana?

From what you’ve seen and experienced, does it seem most of the material flowing into Agbogbloshie is coming directly from developed countries? Or is this material that has been used by consumers inside Ghana?

Akese: The majority of products in Agbogbloshie are things that have been consumed by Ghanaians. Obviously they came from the West. Ghanaians and Africans for a long time have depended on the West for their manufactured goods whether used or new. A recent e-waste assessment, the E-waste Africa project, which used trade data from Ghana customs, interviews, field visits, surveys and stakeholder consultation, noted that of the total imports of electrical and electronic equipment into Ghana in 2009, 70 percent were secondhand goods. Only 15 percent of this secondhand portion could not be repaired. So you would presume that is the percentage that can be declared as e-waste that is dumped. In the face of studies like these, we cannot continue to characterize the transboundary flow of used electronics, especially to Ghana, as a case of illegal dumping just because it’s the informal sector that’s doing that trade. That’s what the informal sector does in most developing countries. They oversee the needed services when the government fails.

McElvaney: You can see shops on the street near Agbogbloshie selling electronics. But what’s happening? They’ll sell a TV without any ability to prove this is really working. People buy a PC or TV for $40, but they don’t know if it really works. So whoever buys it goes home and realizes it’s not working and where is it going then? We know.

Osseo-Asare: But one thing that’s interesting about Ghana – and it applies to electronics and almost every other kind of product – is that a large segment of society feels used products are preferable to new ones. The reason why is that a lot of the new products there are complete pieces of crap made in China for nothing. So if you buy a brand new generator, it will blow out quickly. But if you get an old generator that was built when people made things in a serious way and you repair it, you’ll get years of use out of it. And the parts are stronger, more durable, more robust.

So what’s the next step for helping Agbogbloshie move forward?

Osseo-Asare: I would say invest in the ecosystem, the community of people that are doing this work in the industry. That means not only money and resources, but also expertise and know-how.

McElvaney: I think we should also look at the larger picture. We are all consumers. We should take care more about what we buy and whether it can be repaired and by whom. Also, we should think about whether we are buying quality products or not.

Akese: If anyone here is trading with African traders, they should continue to trade with them because research is showing a huge segment of electronics are being reused in Africa. That’s the only way a lot of people in Africa can connect to information technology. Boycotting African traders does not provide an answer to what is happening in Agbogbloshie. Even if export is banned, there will still be electronics heading to the site because Ghanaians have been consuming electronics long enough to generate their own substantial amount of e-waste. I think the case of Agbogbloshie rests on the Ghana government. The people at Agbogbloshie are trying to provide services in managing e-waste. The government should partner with them and ask, “How can we help make your important work safer for you and the environment?”

Grace Akese can be contacted at [email protected].

Kevin McElvaney can be contacted at [email protected].

DK Osseo-Asare can be contacted at [email protected].