Teton County, Wyo. handles about 4,500 tons of recyclables per year. | Carson Meyer Photography

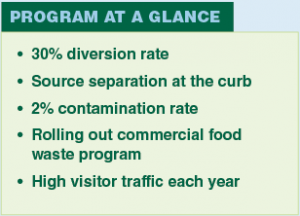

Each year, as many as 3 million visitors come through Teton County, Wyo., drawn in large part by the area’s scenic destinations. With so many out-of-towners coming through, local recycling coordinators have to stay on their toes when it comes to outreach and education.

Teton County Integrated Solid Waste and Recycling provides recycling opportunities for the county’s roughly 23,000 residents, but that doesn’t capture the full service population. Visitors are drawn to the area for Grand Teton National Park, Yellowstone National Park, Jackson Hole Mountain Resort and more.

Overall, the county handles about 4,500 tons of recyclables per year, and it currently has a 30% annual diversion rate. That figure has held steady for the past several years, and to drive it forward, county leaders are looking to tackle new diversion streams.

Program builds around source separation

Recycling in Teton County, located in rural northwest Wyoming, began as a nonprofit operation, and it merged with the county operations in 2009.

The county uses a source separation system with different bins for different materials at the curb. And it sticks to the basics when it comes to the accepted material list. The program accepts PET and HDPE plastic, corrugated cardboard, various grades of paper, aluminum and steel cans, and glass bottles.

“We never went to commingled; we just didn’t have the capacity for that,” said Brenda Ashworth, superintendent of solid waste and recycling for the county.

The county operates a recycling center accepting recyclables, and curbside recycling is provided by private haulers and paid for by residents. The public can also take certain recyclables to a handful of community recycling bins around the county, and they can self-haul a wider variety of materials – including textiles, batteries, books and more – directly to the county facility.

Despite its rural location, the county has markets for all its recyclables, even if materials have to travel across the country. A variety of recyclables go to Salt Lake City, there are a few regional markets for others, and aluminum goes all the way to Alabama.

Despite its rural location, the county has markets for all its recyclables, even if materials have to travel across the country. A variety of recyclables go to Salt Lake City, there are a few regional markets for others, and aluminum goes all the way to Alabama.

Still, Teton County has not been immune to the market pressures of the past couple years.

“The cardboard has been problematic, as it has everywhere,” Ashworth said. “We’re still able to move our cardboard, but that’s a testament to how clean our product is.” OCC comes in source separated – by a residential population that cares greatly about recycling and sustainability – and is hand-sorted again by manual sorters, maximizing its quality.

There is no landfill in Teton County, meaning garbage has to be trucked across the border into Idaho. The county sends four or five semi-truck loads per day on this route.

“Working on that diversion rate, reducing that haul, is critically important to this community,” Ashworth said.

Gateway to natural wonders

With 3 million annual visitors, does the county face any challenges getting the word out about proper recycling?

“Every day,” Ashworth said.

As such, county education efforts span a variety of channels. Sometimes it’s visiting a preschool or local rotary group, sometimes it’s placing ads in the local paper and radio station.

“I take any opportunity I can,” said Carrie Bell, waste and diversion outreach coordinator for the county. One successful outreach effort has been running ads before films at a local movie theater, with the advertising taking the form of a trivia game.

“We really have to hit everything we can to try to get our message out,” Bell said.

With its outreach efforts and source separation system in place, the county has fairly low contamination in its recycling stream: In 2019, county employees pulled just 8 tons of trash out of 4,500 tons of recyclables.

Still, the county wants to reduce improperly placed material even further. For one, even a small amount of contamination can ruin an entire load of recyclables, Ashworth noted.

And the county recycling center relies entirely on manual sorting to remove contaminants; it has a conveyor line and baler, but no sortation equipment. That puts particular importance on boosting recycling purity, and it is even leading to a new outreach campaign.

The goal is to make the public aware that there are people behind the recycling process. The county brought in a photographer to take photos on the recycling facility floor, “to really make that connection that there are humans behind this,” Ashworth said.

Teton County has launched an outreach campaign focused on the human element of

materials processing. | Carson Meyer Photography

Diversion targets drive local progress

In 2014, the county passed a resolution, setting a goal of 60% diversion by 2030. That target has helped push various initiatives to reduce nonrecyclable materials in the waste stream and explore new diversion possibilities.

One recent step was a plastic bag reduction ordinance in the town of Jackson, which makes up a large portion of the county’s population. The ordinance implemented fees on paper and plastic bags provided to customers in the retail setting, with some of the generated funds going to further bag reduction efforts and to pay for free reusable bags being handed out to the public.

According to a county report covering recycling throughout 2019, the ordinance has led to 5 million fewer single-use plastic bags in the waste stream.

“Businesses are reporting positive interactions with their customers about the ordinance while also saving money by not providing bags to every customer for free,” the report stated. “Anecdotal stories trickle in about visitors commenting on how they wish their communities would do the same.”

The county is also exploring additional diversion streams to hit the 2030 target. While the county already provides a composting service for yard waste and other wood waste – these streams make up about 18% of annual diversion – it is now gearing up to provide a food waste diversion service through a pilot program.

The effort follows a successful composting pilot program with food businesses in Grand Teton National Park. That project ran for three seasons and involved collecting food waste from certain kitchen locations in the park. The program saw steady growth and helped program leaders experiment to see what works best.

“From a hauling perspective, bin sizing, bags, wildlife mitigation, do you spray the bins out, all of these logistical things were hammered out in a very small environment that we could control and troubleshoot,” said Bell.

Now, the county is gearing up to roll out a commercial pilot program throughout the county this year. Officials will also be examining additional food waste initiatives in the future.

“We are not going to work on residential until we get commercial up and running,” Ashworth said. That’s despite high public interest in a residential program. Recycling program leaders spoke with other counties that have implemented similar programs, and many had the same piece of advice: Start small, and build from there.

“It’s been really hard for us, but we want to get it right,” Ashworth said.

This article appeared in the February 2020 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.