IM Imagery / Shutterstock

This article appeared in the August 2025 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

The electric vehicle battery recycling business remains in flux, but reasons for optimism remain.

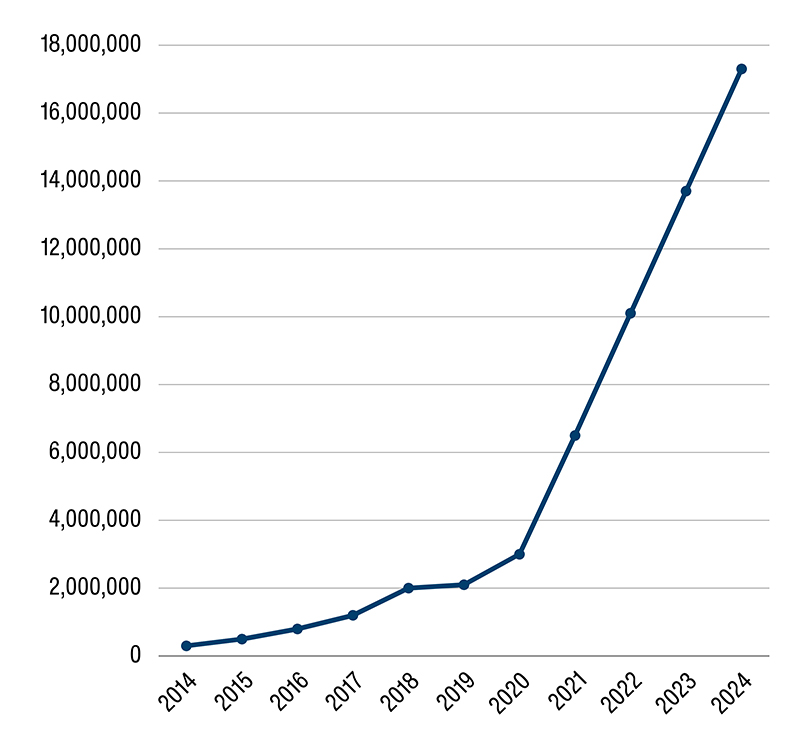

The global electric vehicle (EV) battery recycling market looks a lot different since the modern EV era began nearly 30 years ago, but a series of factors are creating more turbulence than the still-new industry has seen in years.

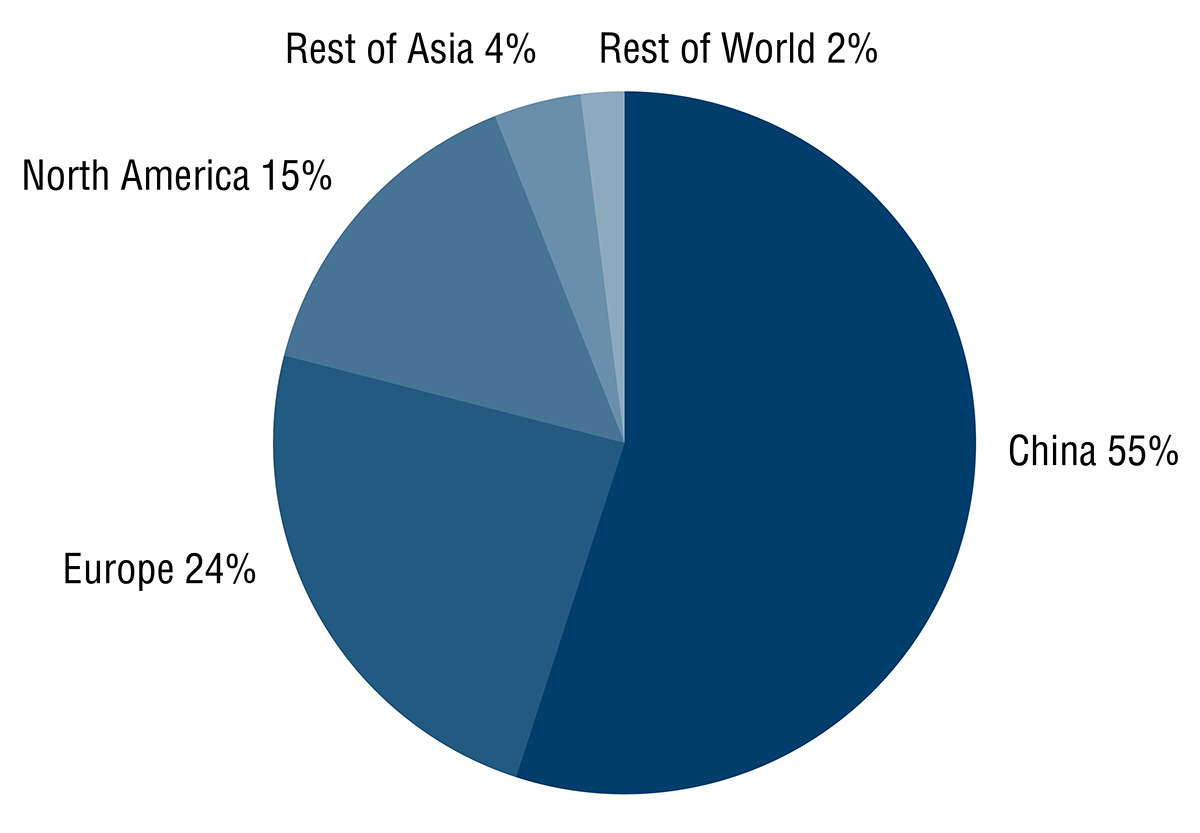

Manufacturers and recyclers in the United States and Europe are still playing catchup to China, which outproduces its global counterparts in EV sales and scrap production. Battery innovation that enhances component life also leaves fewer devices entering the end-of-life stream, leaving recyclers fighting more for fewer end-of-life batteries. Per JD Power, early batteries degraded around 2.3% per year 20 years ago and degrade closer to 1.7% now.

Some of the batteries entering the recycling system contain too few valuable minerals to be financially viable, thanks to falling metal prices. That also makes mining for fresh minerals a riskier proposition, even as supplies of essential elements like lithium dwindle.

Then there’s the shifting political climate created by the second Trump administration.

“People in the industry have to be cautious in the short term,” said Julia Harty, energy transition analyst with the Fastmarkets intelligence firm. “Because it’s a nascent market, a lot of people get really excited without really knowing what they’re doing.”

The road may still be rocky for recyclers and other players in the EV industry, with ongoing regulatory, financial and political uncertainty making it tough to plan a way out. But for those that can persevere, Harty said the future looks bright. “In the long term, there’s a lot to be excited about,” she said.

How battery recycling is done

Recycling specifics can vary, but generally the process starts by breaking apart the battery’s outer casing, according to Battery Recyclers of America, a Texas-based battery recycling management and logistics group. The internal components are then melted, crushed or broken apart. The battery cells and circuits within the battery are crushed to separate the vital metals in them such as nickel and lithium.

Recyclers take the “black mass” of pulverized batteries and remove lingering plastic, steel and other nonvital components, leaving behind the precious metals needed to make new cells.

The global black mass recycling market was valued in 2024 at $13.02 billion, according to Straits Research. That number is expected to grow to $15.17 billion in 2025 and to $51.55 billion by 2033, according to the firm’s estimates, a nearly fourfold increase over only 10 years.

Battery and plug-in hybrid EV global scrap distribution, 2024. | Logoform / Shutterstock | Source: Benchmark Mineral Intelligence

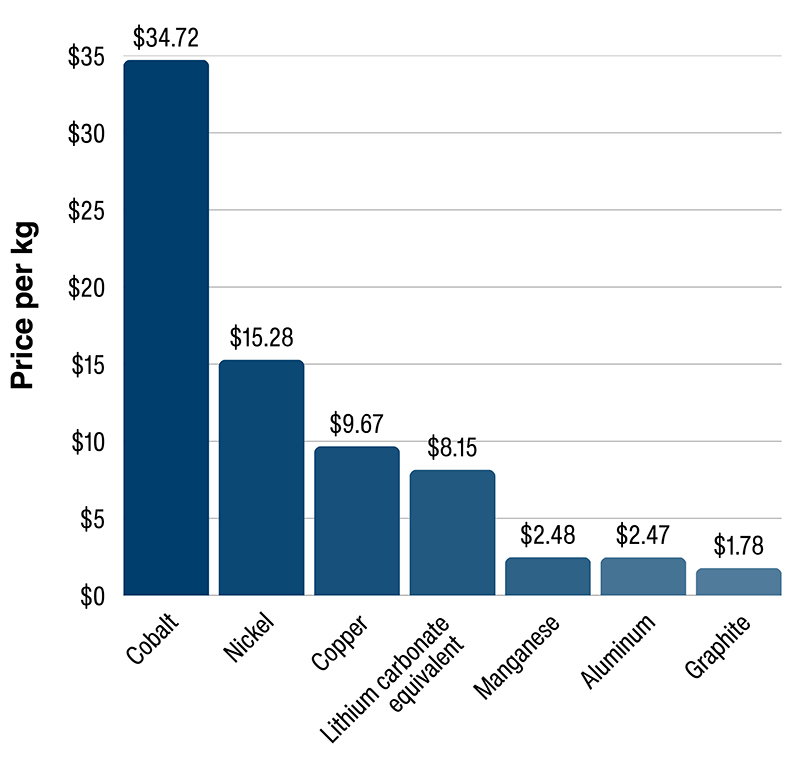

What makes batteries tricky for recyclers is their content. Of the three main types of lithium-ion batteries, nickel-manganese-cobalt (NMC) and nickel-cobalt-aluminum (NCA) batteries contain enough sought after elements to make processing worthwhile. But the third type, lithium-iron-phosphate (LFP), is made of minerals with little value. Since LFP batteries cost around 19% less to make than their counterparts, according to Battery Design, a U.K.-based battery knowledge and data agency, manufacturers stand to gain by switching.

But price fluctuation has taken some of the sheen out of recycling. Lithium prices are down more than 80% from two years ago, according to Fastmarkets data, while cobalt is rebounding but is still worth only about half of what it was two years ago.

“Higher cobalt prices mean if you’re recycling batteries containing them, they contain some cobalt and you’re able to maintain a living,” Harty said. “With LFP, there’s not much to get out of it. I understand why manufacturers are going to LFP … but you have to think about the whole system.”

Adding to that is the fact that not all batteries are designed to be recycled, according to Beatrice Browning, battery recycling technology lead for Benchmark Mineral Intelligence. Incorporating discharge and dismantling into the recycling process makes it more efficient, but also adds to the cost.

Technologies that can accommodate NMC or NCA recycling may not be able to handle LFP batteries, she said, adding more potential cost and difficulty. Making black mass from these batteries can be done through direct recycling and other methods such as chromatography (separating elements by dissolving mixtures in gas or liquid) or hydrometallurgy (extracting elements using aqueous means). These processes can minimize waste but offer low profits, Browning added.

Regulatory landscape

Globally, regulatory differences also impact black mass production and sales. In China—where the industry is years ahead due to lower labor costs and overall production advances—the Ministry of Ecology and Environment announced in June 2025 that black mass can be imported into the country as of August 1, 2025, provided the exporting country doesn’t classify the material as waste or hazardous. That loosens existing regulations and is likely to make even more material available to China.

In the European Union (EU), which has a much smaller black mass refining capacity than China, regulations go into effect in November 2026 that ban black mass shipments to some countries and limit them to others.

“China is only allowed to buy the best black mass on the market,” Harty said. “Most top-level black mass now is going to South Korea.They’ll have to fight for it.”

Since China controls much of the battery refining and production capabilities, U.S. players could find themselves on the short end, according to Steve Christensen, executive director of the Responsible Battery Coalition, a Wisconsin-based group advocating for sustainable battery use and recycling.

“China has proven itself to be an unreliable partner for exporting refined and processed materials,” he said. “Continuing to rely on China for lithium or any other necessary material (that’s part of the) supply chain is a risky proposition.”

Going in the other direction, North American recyclers that have sold black mass to Asian companies have done well, according to Browning. Doing so helps “keep pilot operations afloat and improve the technology on a smaller scale to preserve operations while margins are squeezed,” she said.

Keeping materials stateside proves more difficult due to the differences by state in extended producer responsibility laws, according to Kristen Bujold, communications manager for Cirba Solutions, a battery recycling company. These laws require manufacturers to collect and recycle the products they produce. Working with certified battery recyclers can help navigate these regulations, she said.

“Together, we can keep the minerals in our country and enhance our supply chains so they are more stable,” she said.

Domestic tumult

Battery core material prices as of June 4, 2025. | i viewfinder / Shutterstock | Sources: Fastmarkets, LME

U.S. recycling regulations generally fall in between those of China and the EU, but several unresolved factors could lead to global fallout.

Lower-than-expected growth in EV sales, for starters, may continue sending ripples down the value chain. Automotive tracking agency Edmunds found nearly 300,000 EVs were sold in the first quarter of 2025, up 11.4% year-over-year from 2024. But the overall U.S. transition to EVs has slowed, Edmunds analysts said, as lower price points have made hybrid and plug-in hybrid vehicles a more popular choice.

“As a result, we’re not likely to see the same explosive growth in the coming year,” said Edmunds’ analyst Ronald Montoya in an April report.

The Trump administration’s cancellation of a federal EV tax credit won’t help. New legislation will discontinue a $7,500 discount as of September 30, leaving prospective owners to foot more of the bill.

“That then impacts gigafactories that make batteries, which impacts production scrap and down the chain,” said Harty, whose agency estimated the administration’s actions will reduce U.S. EV sales by 19% in 2028.

Hybrid sales, according to Edmunds, outpaced EVs by more than 313,000 in 2024 and were on pace after the first quarter of 2025 to surpass the 2024 total of 1.2 million. And hybrid sales were even higher in 2024 at 1.5 million, a market share of 9.7% of the electric car market; that market share grew to 11.7% in the first quarter of 2025.

Battery sizes in hybrids, plug-in hybrids and EVs vary from smallest to largest, respectively, impacting the amount of valuable minerals available to recover. Hybrid batteries average about 1 kWh, plug-ins are 21.8 kWh and EVs are 40 to 100 kWh, according to Car and Driver. The size requires far fewer minerals, and hybrids also use nickel-metal hydride batteries in some cases, which with the size combined with the lack of cobalt make them less valuable to recover.

The administration’s anti-environment practices extend to manufacturers, miners and others competing for federal dollars, she added. Rather than focusing on the pro-environmental aspects of recycling, they’re forced to reword requests and documents to put an emphasis on the business need for mineral circularity and how recycling could decrease foreign dependence.

All of this could exacerbate an economic downturn that’s been underway for a while. Canada-based battery recycler Li-Cycle Holdings Corp. announced in May 2025 that it is filing for bankruptcy, a move that ended a planned $700 million recycling hub it was going to build in Rochester, New York. Aspen Aerogels canceled a $1 billion manufacturing plant to be built in Georgia, while KORE Power abandoned plans to build an $850 million plant in Arizona. And in Sweden, Northvolt ceased EV battery production in June after declaring bankruptcy in March.

One area in which the administration has helped the industry, Christensen said, is lithium production. Federal regulators have fast-tracked permitting for projects in Nevada and Oregon, but he feels more could be done.

Global EV sales by year. | i viewfinder / Shutterstock | Source: International Energy Agency

“Many other projects in North Carolina, Arkansas, Pennsylvania and other states across the country could similarly help solve this problem,” he said. “However, without a strong, purposeful permitting reform agenda—a cornerstone of the administration’s efforts since coming into office—these resources could remain untapped.”

Companies that survive can remain viable through innovation, Browning said. The answer involves “exploration into new technologies for recycling, finding approaches that are chemistry agnostic, forming partnerships to ensure the materials they are targeting are uniform, and tailoring recycling solutions to specific cathode chemistries and form factors.”

There’s always a catch

Battery innovation comes at a price, and not just monetarily. The generally accepted EV battery life expectancy is about 13 years, but Browning calls this number conservative. Second-hand EVs at least that old can be found for sale, while Tesla’s 2024 impact report said its battery lifetimes exceed 17 years.

ABI Research estimates that by 2030, there will be four times more EV battery recycling capacity (1.3 million batteries per year) than feedstock (about 341,000 out-of-service batteries). That comes even as mineral demand is set to outpace supply. Fastmarkets estimates expect a 1,500-ton lithium shortage as soon as 2026, with nickel already facing a shortage and cobalt expected to do likewise by the turn of the decade.

Adding to the issue is where these minerals are mined. Altitium, a UK-based clean technology firm, estimates more than half of the world’s nickel comes from Indonesia and two-thirds of all cobalt comes from the Democratic Republic of Congo—two nations with a history of mining-related human rights issues.

When battery recycling picks up, that should help close the gap and alleviate some of these concerns. Harty estimates more than half of all battery minerals will come from recycling by 2030. That will help reduce the need for new feedstock, which is costly and time-consuming: Activating a new mine takes at least three years once a project is launched.

“There shouldn’t be a worry that we will run out of minerals to be mined,” she said. “If you recover your own minerals, you don’t need to worry about mines. The freedom you get as a country from recycling batteries helps gain resource independence.”

Bujold agrees. “When EV batteries are recycled … consumers are contributing to a closed loop approach to battery recycling,” she said.

Charging up the industry

Although EV sales have slowed, they are expected to pick up in the coming years. That, combined with hope that mineral prices will climb and political tensions will ease, leads to what Harty believes could be a bright future for those companies that can pull through.

“If there’s a cost-of-living crisis, people feel cash-poor now,” she said. “When the economy picks up, they will want to spend more. As EV demand continues to wane, most companies have had to pause projects or pivot their focus.”

The same innovation leading to waste battery shortages now could spur long-term business success. Work continues to make LFP recycling more palatable, which would give the innovator a huge head start in feedstock since batteries generally have to be warehoused rather than put into landfills, which is illegal at both the federal and state levels. Creating cheaper recycling methods in general, along with enhancing feedstock partnerships and recovery rates, will get more money flowing as the years go on, Harty said.

Education will also help.

“For consumers, EV battery recycling is going to be essential to ensure that the future supply-demand gap of lithium, nickel and cobalt … can be reduced using these recycling processes, which will help keep raw material prices and battery costs down,” Browning said.

Added Christensen: “We are optimistic that future demand for lithium can be met, and there is great potential for recyclers to process the increasingly large number of lithium-ion batteries in circulation.”

In the short term, Harty noted, the only known quantity is that there’s still a lot about the EV recycling industry that is unknown.

“There have been a lot of radical changes,” she observed. “If you’re trying to have a business plan, sudden change is very bad for business. This time of turbulence is going to be tough for consumers, producers and recyclers. But if there are only a few that cling on and stay in there, they will see the benefit.”

Paul Lane has worked with Resource Recycling since March 2025. His work has also appeared in the New York Times, Buffalo News, American City Business Journals and other publications.