Big Wave Productions/Resource Recycling

In the showdown between recycled and virgin plastic resins, recycling can’t prevail without more supportive public policy, greater buy-in from the public and other outside reinforcements, several plastics recycling leaders agreed in March.

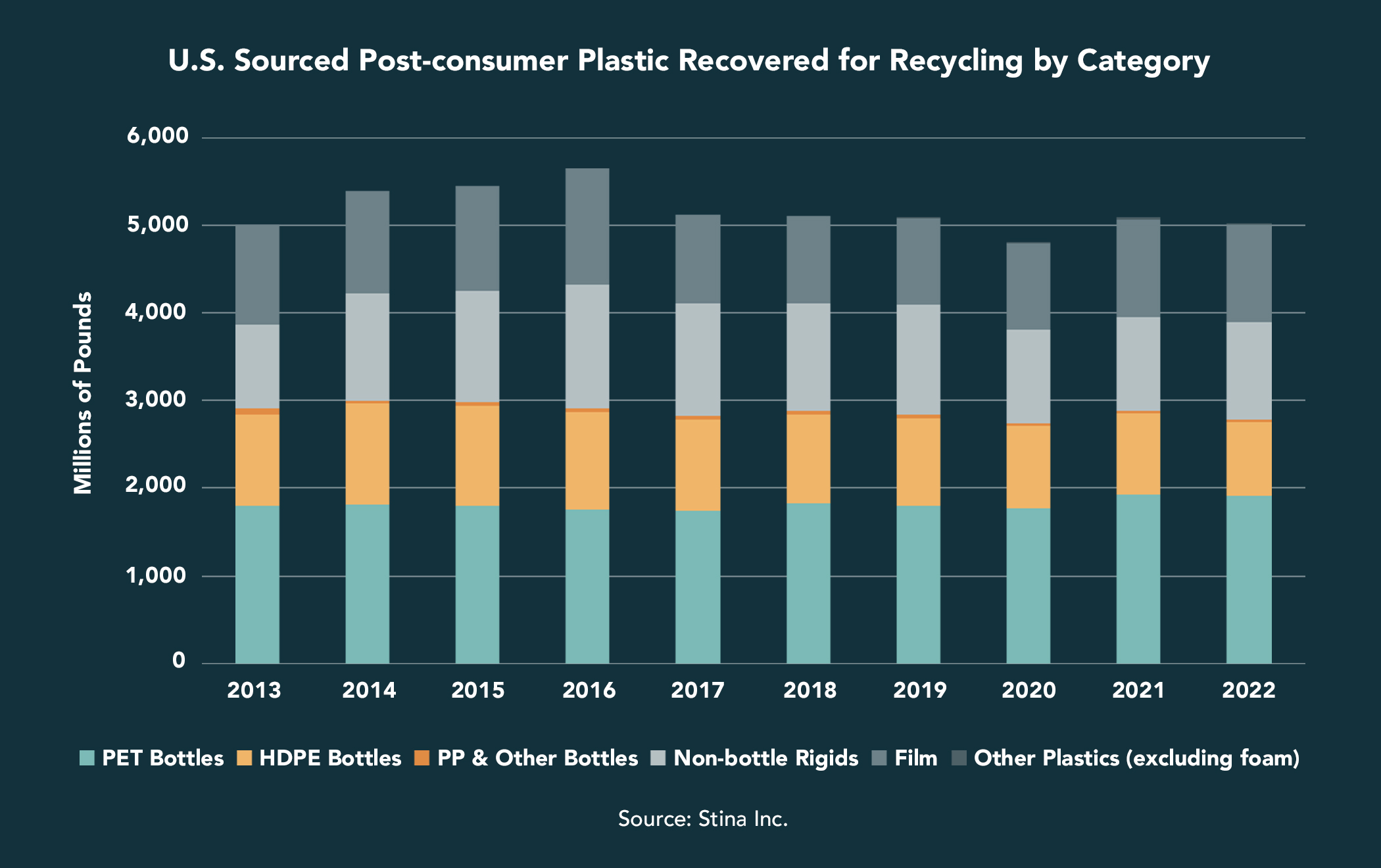

Two numbers make the scale of the imbalance clear. The recycling sector collects roughly 5 billion pounds of bottles, films and other plastics for recycling each year in the U.S., according to the research and consulting firm Stina Inc. U.S. plastic producers, meanwhile, made more than 8 billion pounds of new resin just in the month of February, as tallied by the American Chemistry Council, a national association of chemical manufacturers.

Far from the early days of plastic recycling, when reclaimed resin was seen as a more cost-effective and somewhat embarrassing alternative, recycled plastic is now sought after in many contexts but outcheapened and outmatched by a worldwide glut of the new stuff.

“If we don’t deal with the price differential, at the end of the day – I believe this – nothing we do matters,” Stephen Alexander, president and CEO of the Association of Plastic Recyclers, told an audience during Resource Recycling’s Plastics Recycling Conference in the Dallas area earlier this year. APR owns Resource Recycling, Inc., which publishes this magazine.

“Some call it headwinds we face, I call it the attacks that we face across the board,” he added. “A lot of us are here trying to solve a problem that someone else creates.”

That was one of many takeaways speakers shared at the annual conference, where around 2,500 attendees gathered in Grapevine, Texas, for 20 sessions that delved into product design, artificial intelligence, chemical recycling techniques and other important trends.

The lay of the land

In a series of panel discussions, Alexander and other experts painted a somber picture of an industry in some ways stuck in a rut, though they also identified several levers that could help pry it out. George Smilow, chief operating officer at New York-based PQ Recycling, recalled starting his career back in the 1970s.

“Back then I believe there were about 50 to 60 PET reclaimers in North America, and the return rate was 30%,” he said. “Today there are about half, and the return rate is about 27%.”

New plastic production, on the other hand, has gone gangbusters to the point of overkill, said Joel Morales, vice president of polyolefins Americas for Chemical Market Analytics.

China is a big driver, he said. Many new plants there are tied to fossil fuel refineries, insulating them from low prices amid an oversupply, and projects are also trying to get ahead of anticipated regulation and building difficulties. But it’s a global pattern.

“From a virgin resin supplier perspective, we’ve only added more capacity since last year, and we’ve removed demand in the virgin forecast,” Morales said. “It’s almost like people do exactly the opposite of what we suggest they do.”

On the recycling side, companies and government programs face a disjunction between supply and demand for recycled plastics, with simultaneously too much and too little material on hand. With curbside recycling flat for years, supply can fall short of sustainability goals set by major brands, for example.

Courtesy of Stina Inc.

“The engineering and technology that we use today is amazing compared to when we first started – we can do just about anything. The only thing we can’t engineer is getting more bottles,” Smilow said. “It’s not something that you can just go out and buy. It exists only if people return the bottles and they’re in some sort of a system where we can get those bottles and make something of them, return them to the system.”

Scott Saunders, general manager for KW Plastics in Alabama, said recycling must do a better job of reaching mid-sized, mid-U.S. cities to get more inflow.

“We can build all the lines we want to build, so can Jon,” Saunders said, referring to his co-panelist, Jon Vander Ark, president and CEO of Republic Services – both companies have invested heavily in expanding their recycled plastic processing capacity in the past few years. “If we don’t have the material to put on those lines, it’s just equipment.”

Demand can appear strong at least for certain resins and contexts. After Republic began building facilities to process post-consumer plastic, “we had 50 customers come up to us and say ‘we’ll buy every molecule that comes out the back door of all five of your facilities,’” Vander Ark said.

Yet demand can falter or lag when sustainability goals fall by the wayside in the face of low virgin costs, concerns over food safety or other factors.

Some post-consumer films have received no-objection letters from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for their use in food-grade pouches, but “we’re still seeing some resistance in that actually being commercialized,” said Cherish Changala, vice president of sustainability and public affairs at the Arkansas-based reclaimer Revolution.

“In many cases, you can say they’re able to recycle material, but it’s that demand that’s not there,” she said. “What’s it going to take to get us over that hurdle?”

With all of this in mind, the question posed by a session title – can PCR still compete? – has a clear answer, said panelist David Nix, president of Pennsylvania-based Green Group Consulting.

“No, it can’t compete,” he said, pointing to the myriad collection, shipping, processing and cleaning costs tied around recycling’s neck. “That’s a no-win situation. It’s just not going to work. The things that will make that work are legislation.”

‘Take the devil out of plastics’

Several panelists joined the call for recycling-friendly policy. Nix and Alexander favored state laws requiring that new packages include minimum proportions of recycled content, as some states have done, as a way to essentially force demand into being.

Vander Ark said brands’ verbal commitments don’t always reach into the companies’ cost-focused procurement offices without that legal poke. “That world is starting to rotate because of regulation, and we’re seeing that in California, New Jersey and other states. And that’s the reason why we’re making this investment.”

Boosting recycling tax credits to match other industries, making recycling programs more consistent in the materials they accept and requiring manufacturers to buy their recycled resin domestically would all help as well, Alexander said. Extended producer responsibility seems promising, but he’s waiting to see results.

“The plastics recycling industry is being left behind, because we’re tasked to do it all by ourselves,” he said.

Nina Bellucci Butler, CEO at Stina Inc. and a moderator of two sessions, pressed panelists to keep a deeper need in mind: making recycling worthwhile, in all senses of the word. Recycling does a lot of good, including for the environment and public health, but this isn’t always obvious or tangible for the general public.

“I can either throw it away, where it’s easy, or I can recycle. It’s a little extra effort. There’s no economic benefit for them to do that. So what is the other motivation that they have?” she said. “Is there something that we haven’t thought of yet that really provides the value on PCR, that represents all those things that society actually needs? It is a public service, and we’re not seeing that translated to the reclaimers.”

Brian King, executive vice president of marking at Advanced Drainage Systems out of Ohio, pointed to local policy changes like higher tipping fees for waste than for recycling. More broadly, he said the recycling industry needs to tell its story in a better and more unified way, echoing comments from Alexander and others.

“It is showing what happens to the product, showing what a recycled material does versus a virgin material,” he said, adding that he objects to the pejorative term “downcycling” when his company turns a single-use item into one that can last decades.

“We tend to look for a silver bullet. Chemical recycling’s going to save us all, some EPR is going to save us all, right? And it’s not,” King said. “It’s collaboration, it’s working together.”

When Ajit Perera, vice president of post-consumer operations at Talco Plastics in California, joined the state’s advisory board for its recycled-content law, he was the only plastics person in the room.

“Everyone wants to demonize plastics, let’s not use plastics, let’s go to something different, paper, so on and so forth,” he said of his fellow board members. “And I said my mantra here is actually to take the devil out of the plastics.

“I think we should all be passionate and we should push the word out that plastic is here to stay, and it can be only sustained if we recycle it,” Perera went on. “It’s up to us to go out there and preach.”

This article appeared in the May 2024 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.