This article appeared in the April 2024 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

This past December during the holiday spending frenzy, my husband, Matt, and I took off for a music-filled weekend getaway in Hampton, Virginia. They say Virginia is for lovers, but instead of feeling warm fuzzies, I found myself distracted by miles and miles of clear-cut forests and monoculture tree farms. Matt was finishing up a video conference call, so I was driving without the distraction of conversation, gazing back and forth at the stumps, while listening to his meeting about improving supply chain logistics. I thought about the growth in stuff moving through supply chains, growth in demand for trees to provide cardboard packaging for the stuff, and how long before there’s just nothing left of our untouched natural world with all of these “improvements.”

During this time when consumer purchasing peaks towards helping companies get out of the red and into the black, I find myself fixated on the resources those purchases and their packaging use. Recently we’ve seen more and more companies make a shift to paper and cardboard packaging because of the pushback on single-use plastic packages. As the debate between paper versus plastic continues, it has me pondering the meaning of a Morton’s Fork, a dilemma where two choices lead to the same undesirable conclusion. An article in Science Advances last year showed how our way of life is already exceeding six of nine planetary boundaries, the conditions within which life can survive. I can’t help but worry that a shift to even more paper or cardboard packaging ultimately will lead to different but equally problematic outcomes as our reliance on plastics has.

Concerns around the myriad risks from plastic are finally front and center in the news, but most of us are less familiar with the impacts from the pulp and paper industry. Most know that paper is relatively recyclable and can be a renewable resource. It’s when paper is pushed to function like plastic — e.g., contain liquid — that recyclability issues arise. According to The World Count, paper is quite recyclable, but more than half of the global paper supply comes from newly cut trees, and if everyone consumed paper at the rate of the U.S., Japan and Europe, there would be no trees, much less forests, left. Recycling paper reduces some impacts, such as saving 4,000 kilowatts of energy for every ton recycled. Unfortunately, we are both consuming more than is sustainable and not recycling enough of most materials in the U.S. The decision between paper and plastic isn’t so clear-cut. It’s a Morton’s Fork.

STINA INC.’S GUIDE TO THE NORTH STAR

I’m a fan of visionaries like the late Buckminster Fuller and Kim Stanley Robinson who inspire us to think differently and move beyond Morton’s Forks. Their creations spark hope for a world in which we learn to invest in what helps us truly thrive on Earth. Can we resolve this old paper-versus-plastic debate? Maybe not, but I think it’s more imperative to elevate the discussion to the exploration of a new economic paradigm. One that’s regenerative rather than extractive. One that offers the opportunity to sustain life on Earth. This is humanity’s collective North Star. Below is a high-level view of Stina Inc.’s guide to reaching this North Star.

Transparency and accountability offer the catalysts needed to pull us out of the linear model of take-make-waste and into a circular, nature-based economy that allows life to thrive on our planet. Towards that end, we created the CircularityInAction.com platform to feature inspiration from a growing network of people working to preserve resources, recover resources and drive full cost accounting for appropriate offsets or insets.

A ROADMAP NEEDED—PLASTIC FILM CALLS THE QUESTION

Plastic film, in particular, exposes the need for a shared roadmap on how to manage resources sustainably — one that helps us all navigate the decision of what material to use for a given purpose to achieve the least environmental impact, ideally aid in the regeneration of nature, and then best recover such materials after use.

Companies know the advantages of film packaging. Without clear and impactful sustainability goals and metrics — that North Star — guiding decisions, the short-term economic goals and metrics will continue to run the show. It poses significant risk to people, planet and companies as well, which are increasingly called out by watchdog groups and shareholders for “greencrowding,” or joining a coalition or adopting a group initiative and then moving at the pace of the slowest participant rather than putting the efforts and resources towards needed initiatives.

While plastic film is a highly efficient package, it is one of the largest portions of the plastic waste stream and doesn’t have a large-scale, viable recycling option.

Plastic film:

• Has slowed the total growth of waste as it carries more product with less packaging.

• Is lighter and takes up a fraction of the space to ship than equivalent forms of paper or cardboard packaging. Film also reduces fuel consumption and associated greenhouse gas emissions during transport compared to heavier alternatives.

• Use has grown exponentially as companies seek ways to cut costs, reduce fuel consumption and reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Use has also grown out of convenience. The COVID-19 pandemic fully normalized online shopping and things like take-out meals.

• Even as some retailers have switched from plastic to paper for grocery bags at the checkout, film packaging continues to grow in the retail environment, such as baby carrot bags, bread bags and so on.

Film recycling has seen some years of growth, first due to domestic recyclers with initial seed money from petrochemical companies, and then due to demand from export markets. In more recent years, domestic film collection has continued largely as a function of demand for composite decking. Companies with vertical integration of recycling and manufacturing, such as Trex Company, manufacturer of composite decking, tend to weather headwinds better than the companies that buy baled scrap plastic to produce post-consumer resin. But in an economic system which saw a record $7 trillion in fossil fuel subsidies last year, most companies producing items struggle with the fiscal commitment to use recycled content over new or

“virgin” plastics. Until incentives are reversed, the growth in collection and recycling will not be in the same order of magnitude as virgin plastic extraction and production.

The pilots and initiatives to increase plastic recycling that were supported by the plastics industry up until 2022, in the wake of the shale gas revolution, had potential but were funded at a fraction of the amount of other advocacy or lobbying efforts to promote plastics. Ironically, growth in use of plastics has created less demand for oil and gas. Not just film, but all plastics are light, which means less fuel is required in the transport of goods. As we hopefully transition away from fossil fuels for transportation and energy, petrochemical companies seek new markets to offset that loss in demand. Plastics and base chemicals production are forecast to grow.

Due to these systemic challenges, plastic recycling rates overall have remained stagnant over the last 30 years. So the cycle continues: grants awarded, investments made, pilots started, some exemplar facilities built and many businesses failed. And then a new crop of consultants, nonprofits or entrepreneurs emerge and recycle ideas to raise the next round of funds. Ultimately, recycling might net small increases, but we aren’t moving the needle.

SEARCHING FOR ECONOMIC INSTRUMENTS FOR RECYCLING INSTEAD OF UNICORNS

Ralph Chami, my friend and a world-renowned economist, taught me that you need an instrument for every objective you want to achieve. A fundamental objective is to protect the planet on which we live. If we know we must preserve resources and recover resources used rather than trash the planet, then we must be lacking appropriate economic instruments.

Since plastics are a function of extraction of oil and gas, which benefit from government subsidies, the economics of recycling are stifled. Fiscal commitments to recycling are not attractive because of the economic realities: Disposal costs and “virgin” plastics costs are artificially low due to externalizing the true cost of waste on communities and the environment and other forms of implicit and explicit subsidies. Maintaining low disposal costs and cheap fossil fuels, and thus plastics, are essential market conditions for a linear consumer-based economy.

In the case of plastic film, millions of Americans still don’t know they can recycle their clean, dry plastic film such as bread bags, bathroom tissue overwrap, air pillows and case wrap through store drop-off programs. Millions more likely don’t care or just don’t have the luxury of worrying about things beyond figuring out how to meet their family’s immediate needs. Even if everyone did understand how to recycle right, the reality is our economic system simply does not support the business of recycling.

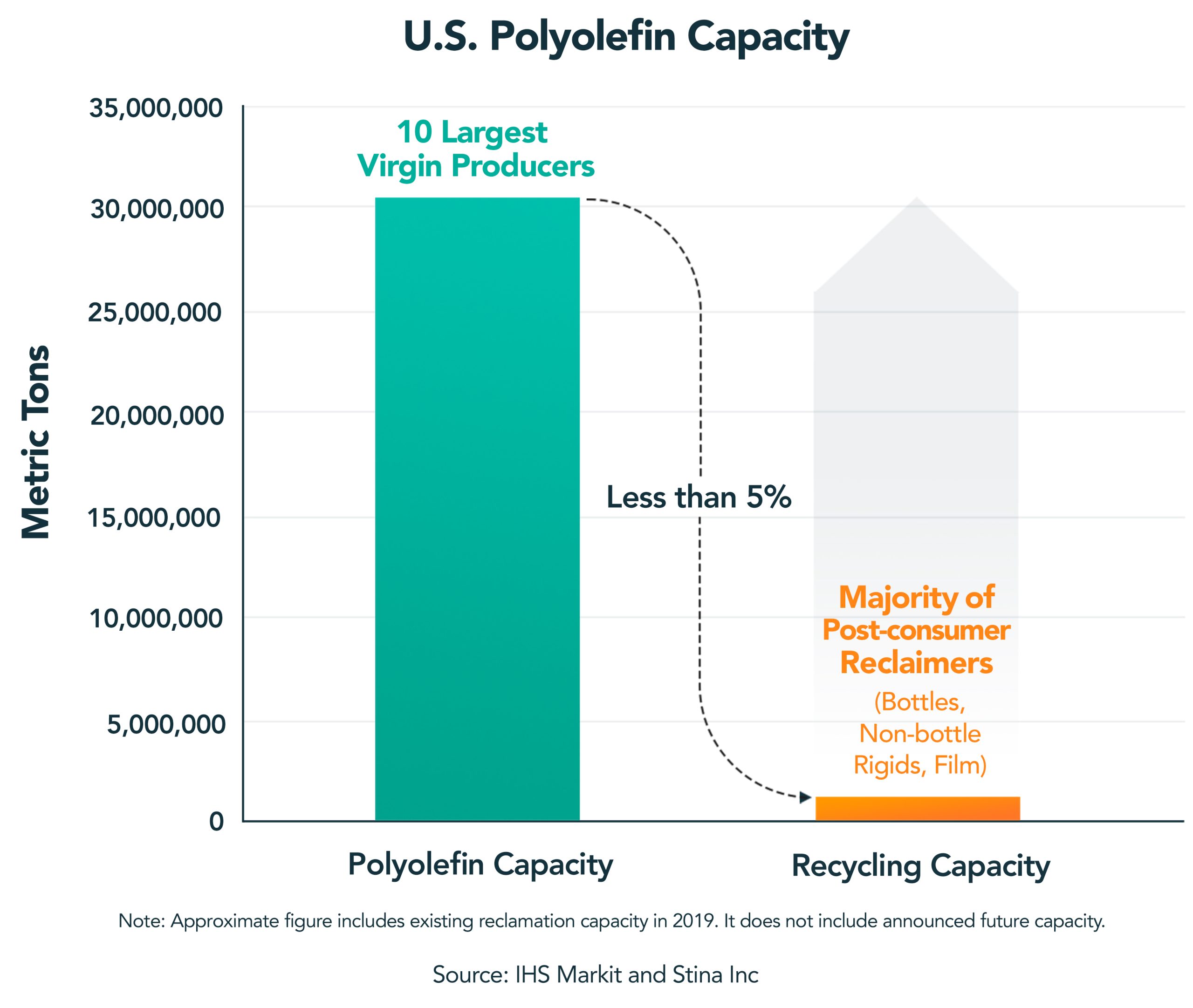

It is a relief that more companies are designing for recyclability, but again our focus can’t be siloed — it is an interconnected system. The reclamation capacity is about 5% of the plastic resin production capacity for polyethylene, based on our decades of research and data from Chemical Market Analytics. With nearly $56 billion in profit in 2022, ExxonMobil illustrated how economics are stacked against recyclers and favor companies that fuel the consumption-based economy.

Recyclers, which are the engines of the recycling economy, not only face steep economic challenges but are also forced to innovate constantly to adapt to the rapidly changing stream of materials.

We need to see as much investment from companies in using

recycled materials in their products and using products with recycled content as there is in achieving recyclability. There is a lot of plastic out in the world but too few channels open to getting the material back into commerce. Due to such little value placed on recovered goods or recycled content, there is little return on investment for large-scale infrastructure to collect, sort and reprocess plastic. Given we can order things for delivery overnight, the logistics exist to build a network of recovery, just not the economic drivers.

CLOSE OF A CHAPTER THAT TAUGHT US A LOT – SHUTTING DOWN A 20-YEAR-OLD DIRECTORY

As CEO of Stina Inc., a mission-based environmental research and technology company, it’s my job to examine the impact of our company’s work. This year, I am contemplating what impact our decision to deactivate the plastic Film Drop-off Directory last November might have. With wars flattening action on climate change and plastic pollution, it feels silly to focus on the loss of our recycling directory for plastic film and bags.

But the world keeps turning, and film keeps finding its way into my house. So if I still recycle my film through store drop-off like the millions of visitors to the site, why did Stina Inc. shut down the Film Drop-off Directory?

Stina Inc. started the directory over 20 years ago to help businesses and consumers deal with a ubiquitous material. The goal was to encourage people to bring back their household bags and film for recycling along with their reusable bags to stores.

Drop-off lists from retailers and insights from recyclers, combined with feedback from the many visitors to the resource, enabled us to provide the most accurate directory possible. We vetted store listings and relied on feedback from users for on-the-ground checks on whether stores were maintaining their programs. Our team updated listings and responded to inquiries daily. We erred on the side of caution, removing listings if we were unable to verify a store had a bin in place or if the material was going to a recycler. We also separately track market dynamics and the amount of plastic film collected for recycling year over year.

For many years, there were reasons to be optimistic. Groups like the Flexible Film Recycling Group were ready and willing to support education about recycling “beyond the bag” through retail collection and, more importantly, grow a network of recovery for the much larger commercial stream. At the table were recyclers, brand companies, converters, producers and local and state governments. The directory saw tremendous growth in user traffic over the last decade. In its last year online, it averaged one search every 55 seconds.

GreenBlue commissioned Stina Inc. in 2022 to facilitate a stakeholder group of 17 representatives from government agencies, retailers, film producers, industry groups and environmentalists to review and update the methodology for determining the availability of recycling through drop-off and how to vet drop-off locations. We reached consensus among the stakeholders and published the summary of the methodology update process. Circularity, like collaboration, is difficult but so necessary, and transparency and engagement with key stakeholders is critical.

Late in 2022 we lost industry sponsorship for the directory. Contrary to consumer perception, the directory was not supported through labeling programs or brand companies that used the labels. For nearly a year, Stina Inc. self-funded the resource to help people recycle household plastic film while asking for support from the film value chain.

More than six film recyclers joined the film recycling steering committee to direct the content of BagandFilmRecycling.org. Late in 2023, three brand companies stepped up to keep the directory active. However, it was not enough for our team to continue to vet and verify information for the site or provide the support needed to develop a healthy recovery ecosystem for film. Maintaining a resource without industry engagement is an exercise in futility. The final factors in our decision to shut down the directory were the announcements by other organizations of the desire to duplicate it.

It’s not easy to build a good film drop-off directory, but it doesn’t take rocket science, either. You need to know the recyclers so you can triangulate information, like where the material is ending up, but I think it was the nuances in information about the plastic film recycling landscape that made Stina Inc. well suited to support this type of resource and the recyclers still swimming against the tide. We remain fully committed to collaboration and engaging with players in the value chain to support recycling.

Accurate information is important to us. The most credible

alternative to the directory that we can offer is the NexTrex website. There, you can find a list of retail chains by state to take your film and be confident it gets recycled.

There are such great opportunities to turn waning confidence in recycling into real demonstrations of circularity, but it requires focus beyond labeling and collection: supporting the existing drop-off collection infrastructure until new collection opportunities become widespread, providing transparency where the collected material is recycled, and long-term agreements by companies to use recycled content produced from their packaging to stimulate demand.

Without legitimate acts to close the delta between supply and demand for recycled plastics, any future film drop-off directory will fall short of helping increase film recycling. We at Stina Inc. remain open to facilitating a collaborative directory focused on recyclers. We have critical data and technical skills to share the data and illuminate opportunities to shift beyond business as usual.

EVOLVING BEYOND BUSINESS AS USUAL

For the last six years our company has been shifting, learning and gathering information. We evolved out of Moore Recycling Associates, a consulting and management company, and have restructured as a research and technology company. We have forged new partnerships that demonstrate that collaboration is better than competition for us in fulfilling our mission and vision, a shift we believe is essential in the transition from a linear economy to a circular one.

We are focused on the collective North Star and excited to partner with others to illuminate the guide to sustainable use of resources to sustain life on Earth. As a quote attributed to Buckminster Fuller says, you never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.

As shown in our Sustaining Life on Earth diagram, we believe that full cost accounting is needed to truly unlock the innovation needed to move beyond Morton’s Fork and the options that fail to sustain life on Earth.

Documenting the state of how material is collected, recycled and made into new products is needed if the public is to have any faith in recycling. Greater transparency and value for what sustains life is needed to drive the economic instruments that will lead to more sustainable use of resources. Reports and sound bites that state recycling is a sham and discourage people from recycling are a distraction.

“In 2019, the latest year of data at the time of writing, we mined, dug, and blasted more materials from the earth’s surface than the sum total of everything we extracted from the dawn of humanity all the way through 1950,” wrote Ed Conway in his recent book, “Material World: The Six Raw Materials That Shape Modern Civilization.”

“For every tonne of fossil fuels, we exploit 6 tonnes of other materials — mostly sand and stone, but also metals, salts, and chemicals,” Conway continued. “Even as we citizens of the ethereal world pare back our consumption of fossil fuels, we have redoubled our consumption of everything else. But, somehow, we have deluded ourselves into believing precisely the opposite. My hunch is that this partly comes back to data — or lack of it.”

With better access to data, perhaps in our lifetime, use of “virgin” materials will become passe and recycled materials will become the sexier option. We already have more human-made material than all living biomass on Earth, according to a 2020 study in the journal Nature. Recycling has to become the norm in manufacturing. Beyond recycling, we need to focus on rethinking systems and designing towards reducing, reusing, avoiding toxic materials and supporting organizations that protect communities and ecosystems from waste.

Moving forward, Stina Inc. will continue our work on the Annual Plastic Recycling Study to report on how much film and other plastics are recovered for recycling, with efforts to document more in the plastic recycling landscape. We will continue to provide tools a directory of recyclers and a recycled products directory to connect people to products that facilitate recycling beyond collection. Please also join us at CircularityinAction.com. We will be working to get more information up on how to support the transition to a circular economy to sustain life on Earth in addition to supporting the engines of the

recycling economy — recyclers. We look forward to collaborating with organizations working to lead on implementing the changes needed to transition to circularity. It’s past time to rethink business as usual.

What We All Can Do

While systemic change is needed, we can also make differences as ordinary individuals. Some ideas for how to catalyze the shift to circularity:

• Stop, think and avoid unnecessary and/or toxic stuff. Below are some apps that provide insights about potentially toxic ingredients.

• ewg.org/apps

• yuka.io/en

• Buy local.

• Re-embrace reuse. Find a favorite reusable mug, bag, cutlery, water bottle and storage container. I keep them in my backpack or stash in the car. Check out Upstream, Litterless and the Refillery Collective for lists of refill and zero-waste stores near you.

• Recycle items your community recycling program accepts.

• Continue taking bag and film items such as clean, dry bread bags and bathroom tissue overwrap to participating retailers.

• Buy recycled to help close the loop in the recycling economy.

• Pick up litter any time you see it to prevent more microplastic and marine debris.

• Donate to local organizations working on cleaning up and regenerating natural ecosystems. For example, I support the Plastic Ocean Project.

• Send your feedback to companies and policymakers.

• Get outside for a walk or other activity to enjoy the outdoors every day.

• Grow something: food, native plants, trees, etc.

Nina Bellucci Butler is the CEO of Stina Inc., which is a mission-based research and technology company providing unbiased guidance to governments, industry, and NGOs in the movement toward circularity, navigating choices to preserve and recover the resources we use. The reality of plastics and plastic recycling has been a key focus of Stina Inc.’s work.

This article appeared in the April 2024 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.