This article appeared in the December 2023 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

When communities set up their recycling programs, glass containers are typically included in the suite of accepted materials. Resident demand for glass recycling remains constant and glass recycling can be a crucial part of helping communities reach their diversion goals.

However, glass also has many unique features worthy of consideration when planning the best way to recycle glass in a specific region. Many misconceptions persist regarding the glass recycling process and why programs are or are not successful, but community leaders must be armed with an understanding of the glass recycling value chain in order to make informed, effective decisions regarding their programs.

A regional approach

One quality that sets glass apart from many of the other commonly recycled commodities (for example, cardboard or aluminum cans) is that the markets for glass are almost always regional. The Glass Recycling Coalition, a collaborative group that builds opportunities for glass as a core recyclable, hosts a glass recycling infrastructure map of the U.S. The map shows that glass recycling infrastructure is clustered regionally, with many areas of the country lacking end markets, beneficiation facilities or even a MRF that accepts glass.

Although plastics and paper are often shipped all over the country and beyond, recycled glass is rarely hauled more than 200 miles to a beneficiation facility. (A beneficiation facility is a secondary processing plant that uses highly advanced sorting and cleaning equipment to produce market-ready cullet.) Recycled glass has a fairly steady value, depending on the quality of the material. However, for the typical glass container mix from MRFs, which is mixed with other commodity fines and residue, the price does not typically offset the cost of shipping glass long distances because glass is heavy and therefore expensive to transport via truck or rail. This also explains why some parts of the country do not have access to glass recycling, despite the willingness and desire of the residents living in these areas to recycle glass.

“Unlike many other recycled materials processed by MRFs, glass cannot be baled,” said Lydia Gibson, director of sustainability and strategic analysis at Strategic Materials Inc. (SMI), North America’s largest glass recycler. “It is also heavy, requiring different transportation methods that can be expensive and limit how far the glass can travel for beneficiation.” Because of these economic and geographic limitations, the most successful glass recycling programs are the ones that create a circular system within populated areas.

“The Glass Recycling Coalition (GRC) has a number of resources, including the infrastructure map, MRF certification and the guides to glass recycling, that can help communities prioritize glass recycling,” said Scott DeFife, president of the Glass Packaging Institute, who also sits on the Leadership Committee for the GRC. “We hope these resources help community leaders make decisions that are right for their area to create strong glass recycling programs and ultimately help get more glass back into the new products.”

The upside of regionality

However, there are many benefits to creating a closed-loop, regional system for glass recycling. One of the most important benefits is that a smaller geographic footprint also means a smaller carbon footprint for the glass traveling to its destination. End-market buyers of glass – primarily food and drink container manufacturers and fiberglass manufacturers – have sustainability goals they are trying to achieve, and using recycled cullet helps them meet these goals by decreasing the amount of energy needed to manufacture their products. Sourcing local recycled glass as a manufacturing input can also lessen the company’s scope 3 emissions, because the raw materials needed for manufacturing these products might be sourced from farther away and have a larger carbon footprint. Additionally, shipping glass to closer locations reduces the costs associated with transportation.

Additionally, circular glass markets support the local economy. For example, in Texas a salsa jar generated from a household in Fort Worth supports jobs at the MRF in Arlington 15 miles away, which then supports jobs at the beneficiation facility 23 miles away before it makes its way to Owens Corning, just 9 miles down the road. The salsa jar traveled less than 50 miles before being turned into a new product, and all along its journey, local jobs and companies were supported.

“Because glass is heavy and bulky, proximate end markets help preserve the value of glass, resulting in the best economic and environmental impact,” said Gibson of SMI. “The circular economy of glass thrives when the entire value chain is localized.”

Hurdles remain

Of course, there are challenges to maintaining this kind of circular loop for glass. Without access to a constant influx of material from all over the country, many of the beneficiation facilities in the U.S. are operating under capacity, meaning they have room to take more glass for processing. However, it is difficult and not always environmentally or economically efficient to get that material to them from communities more than 200 miles away, creating supply and demand issues. Beneficiation plants may need more material, and plenty of glass is generated in the U.S., but getting it from one place to another is another question entirely.

On the other hand, if communities do not have a beneficiation facility or an end market nearby, they are not able to easily recycle glass and will either have to landfill the material or find another use for it. Some communities have been able to divert glass by crushing it into landscape material or using it for roadbed or other municipal infrastructure projects, but this is not the highest and best use of a material that is endlessly recyclable and can be made into new products.

In some instances, it might make economic sense for a community to send its glass by rail to a beneficiation facility, especially if the glass is clean and has higher value. For example, Michigan bottle bill glass is shipped to Glass to Glass in Colorado because it is high-quality glass collected separately from other materials, making it worth the cost of shipping it by rail.

There are a number of real-life examples of the glass circular economy at play across the country. The Glass Recycling Coalition’s glass recycling infrastructure map provides a comprehensive visual of where the systems work well and where there are major gaps in glass recycling. Three areas that have circular systems, albeit all very different in nature, are Texas, Colorado’s front range and the Pacific Northwest.

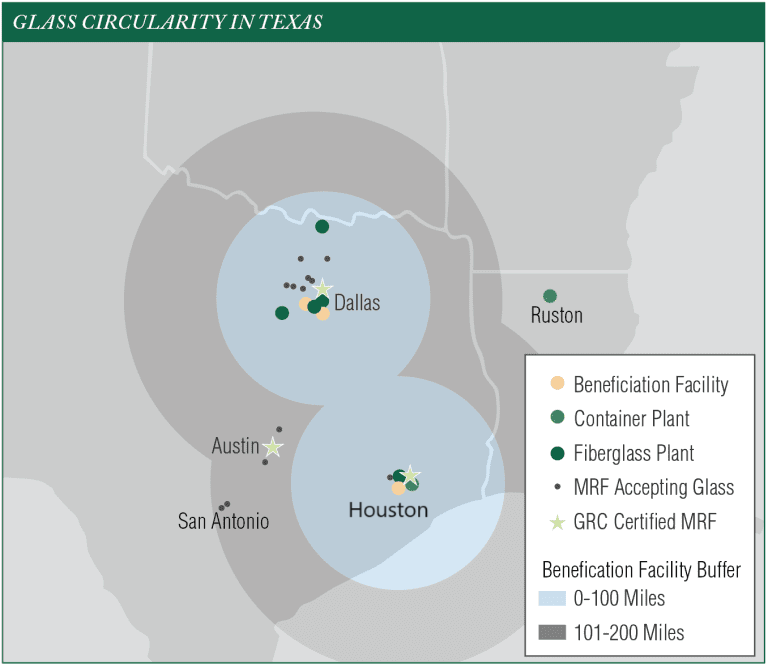

Glass circularity in Texas

Texas is the second largest state in the U.S., both by population size and land

mass. This means Texas is a highly desirable destination for recycling company investment because there is a lot of uncaptured material. It also makes it challenging to move recyclables from communities across the state to their end markets. However, Texas has strong glass recycling infrastructure for communities in the North Texas and Gulf Coast regions.

SMI operates two beneficiation plants in Texas: one in Midlothian, outside of Dallas, and one in Houston, where SMI’s headquarters is also located. Additionally, Dlubak Glass operates a facility in Waxahachie, also outside of Dallas, as an additional secondary processing option. Both facilities source material from communities in these regions, which represent around 14 million Texans. Glass from these beneficiation plants then gets sent to one of the state’s three fiberglass manufacturing plants (four, when Knauf opens its new plant in 2024) and Ardagh’s container plant in Houston.

Although markets in the Houston and Dallas areas are strong, Texas still struggles with recycling access due to a large population that lives in the state’s rural areas. Keep Texas Recycling is a program of Keep Texas Beautiful (KTB) that works with rural communities to establish drop off programs for recycling. KTB hopes to find ways to add glass to the list of materials it takes in communities that are farther removed from end markets.

“Although the drop-off model is a prime opportunity to collect source-separated, high-quality glass, limited access to markets and high transportation costs exceed the budget of many rural recycling programs in Texas,” said Zoë Killian, program manager of Keep Texas Recycling.

In the future, KTB is hoping to support the communities it works with and their willingness to recycle glass by setting up hub-and-spoke programs that allow glass to be aggregated in one location, leading to economies of scale that make it feasible to transport glass to end markets.

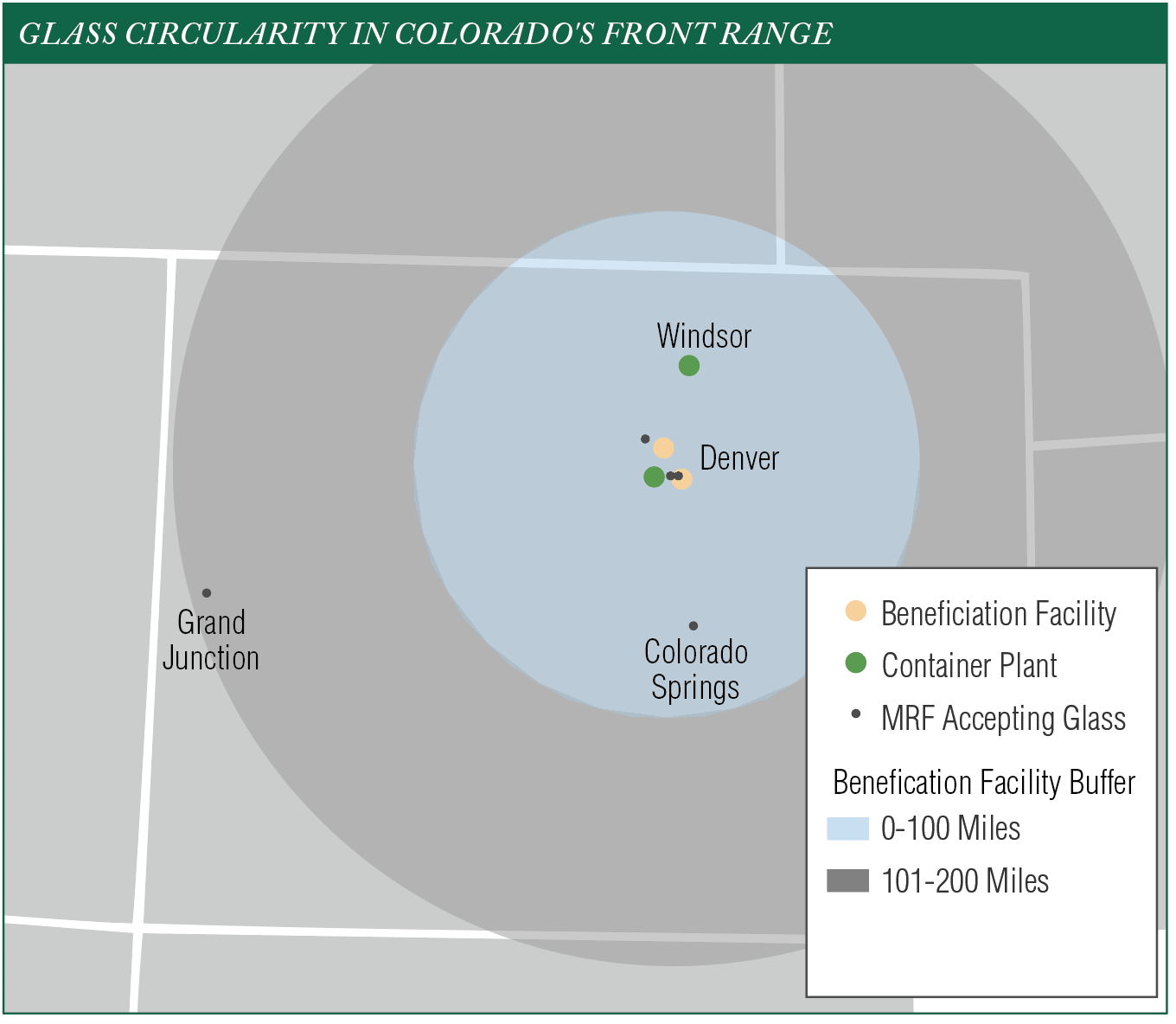

Glass circularity in Colorado

Colorado is divided in half by the Rocky Mountains, and more than 85% of its waste comes from the Front Range of Colorado – the area to the east of the mountains. The Front Range consists of the cities of Colorado Springs, Denver, Boulder and Fort Collins, where most of the state’s population resides. It is also where most of the glass (approximately 191,000 tons) in Colorado is generated and where the markets for glass are located.

In 2021, 41,764 tons of glass in Colorado were diverted, according to the Colorado Department of Health and the Environment (CDPHE). Most of the glass generated in Colorado, both from MRFs and from drop-off programs, heads to the state’s main beneficiation facility, Glass to Glass in Centennial, Colo. O-I Glass took over the facility in 2022 to feed its Windsor, Colo. container manufacturing plant and Rocky Mountain Bottle Company, a container plant just outside of Denver that is co-owned by MillerCoors and O-I Glass. Rocky Mountain Bottle Company also has a small secondary processing operation on site, where it takes small amounts of drop-off glass.

“Glass is at its best when it is produced, filled, used, and recycled locally,” said Robert Hippert, Sustainability Strategy Leader for O-I Glass and also a member of the Glass Recycling Coalition’s Leadership Committee. “Glass packaging is infinitely recyclable, making it ideal for the circular economy.”

In recent years, O-I Glass has created 27 collection sites as part of seven community recycling programs in areas where they manufacture glass containers. Some of these efforts are part of O-I’s “Glass4Good” program, which generates charitable donations based on local collection of glass packaging. In 2022, O-I Glass’ closed-loop programs across the globe kept more than 100,000 tons of glass in the circular system.

“At O-I, we see tremendous opportunity to positively impact the planet and communities where we operate. We partner closely with the communities that we share by investing in equipment and programs to establish local collection of glass packing,” Hippert said. “O-I is partnering with customers to bring unused glass from filling sites to O-I plants, creating circularity, reducing waste and helping increase recycled content in O-I containers.”

Glass circularity in the Pacific Northwest

Neither Seattle, Wash. nor Portland, Ore. are strangers to recycling, and both areas have had strong materials management programs for decades. Oregon is also a bottle bill state, with an annual return rate for beverage containers averaging between 80% and 90% (this includes aluminum and plastic containers in addition to glass containers). Although Washington is not a bottle bill state, it still has strong recycling programs, and in 2018, the glass container recycling rate was 47%, according to the Washington Recycling Development Center. Between Oregon and Washington, a lot of glass is recovered and sent to regional facilities for processing and end use.

In Seattle, SMI runs a beneficiation facility that is co-located next to Ardagh Glass, a container manufacturer. According to a report on glass recycling by the Washington Department of Commerce, in 2019 SMI sent 73% of its glass to Ardagh and 11% of its glass to O-I Glass in Kalama, Wash., just north of Portland, Ore. In Portland, Ore., glass is processed and cleaned at Glass to Glass, a beneficiation plant located down the road from O-I’s plant. The strong markets in the Pacific Northwest, supported by strong recycling programs, ensure that the circular economy of glass is efficient and effective.

The above three examples show how a regional approach, in conjunction with robust end markets and collaboration across the value chain, can ensure that recycled glass ends up in new items – instead of in landfills.

Sara Nichols is a consultant for Resource Recycling Systems (RRS) with 10 years of experience in nonprofit leadership and materials management. She can be reached at [email protected].

This article appeared in the December 2023 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.