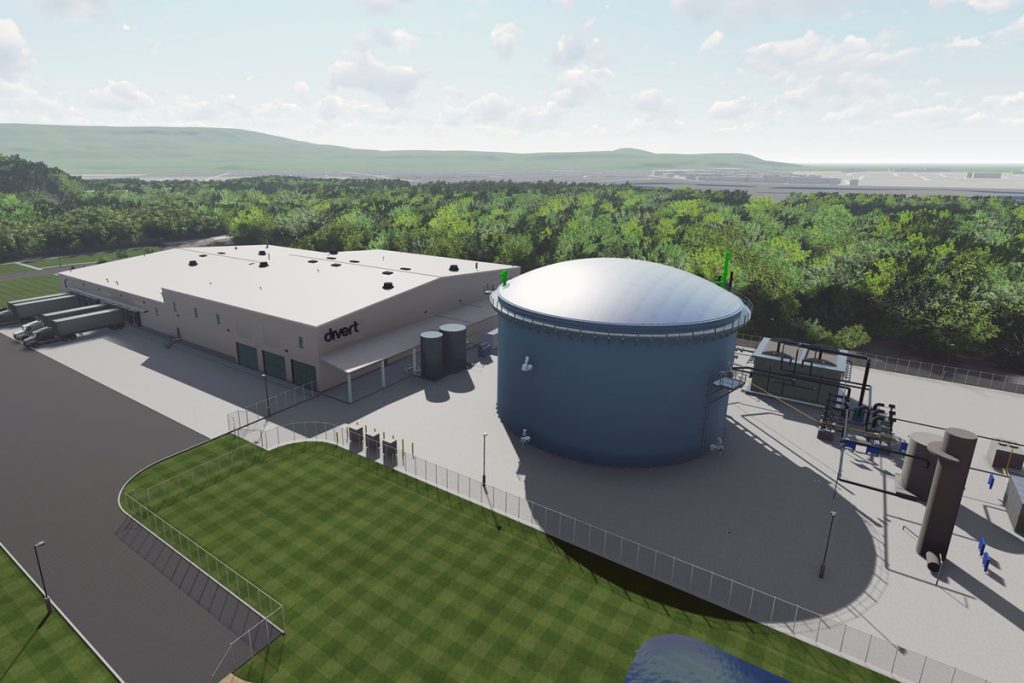

Divert is building an Integrated Diversion and Energy facility in Longview, Wash. that will have the capacity to process 100,000 tons of food scraps into natural gas annually. | Courtesy of Divert

Compost facility projects are heating up as Divert and Bioenergy Devco commence construction on new spaces. Meanwhile, there’s also been some policy movement around compostable packaging.

On Sept. 12, the Biodegradable Products Institute (BPI) filed a petition with the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) asking it to update a decades-old definition of compost in the National Organic Program, noting in a press release that its member organizations urged it to do so.

“Because of discrepancies between federal and state definitions of ‘compost,’ many local composters are unable to take discarded waste/feedstock that has the ability to be composted,” a press release noted. “The petition calls for the federal government to align with states to meet waste diversion goals moving forward.”

Policy push

The crux of the definition issue is that according to current regulations, compostable packing is not allowed in certified organic compost, which creates challenges when sorting the materials. The regulations were written before today’s certified compostable packaging was developed and when composting was viewed as an on-farm activity, the press release noted.

“The world has changed,” the press release stated. “There are now thousands of commercial-scale composting operations diverting yard trimmings across the U.S., several hundred of which also compost food scraps and food-soiled packaging.”

BPI noted that while the update is simple, “the impact will be huge,” especially for states that have set high targets for diversion, such as California and Washington.

Tim Dewey-Mattia, recycling and public education manager for Napa Recycling in California, said that separating out packaging drives up costs and “it would be incredibly beneficial for composters like Napa Recycling if the federal regulation were changed to allow these materials to stay together.”

Anaerobic digestion plant

Bioenergy Devco in September received air and wastewater permitting approval from Delaware’s Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Control to build an anaerobic digestion facility at its Bioenergy Innovation Center in Seaford, Del.

It’s now planning to form an advisory committee for the project to get feedback from community stakeholders about the facility, which will use anaerobic digestion to turn organic food scraps into natural gas and a soil amendment for use in agriculture, horticulture projects and community gardens.

Over the company’s 25 years of operation, it’s built over 250 anaerobic digesters in Europe and the United States. It also manages 140 anaerobic digesters.

Shawn Kreloff, Bioenergy Devco CEO, said in a press release that the facility is “an excellent example of how we can harness renewable energy resources from recycling organic waste and simultaneously contribute to a more sustainable future.”

“Organics recycling is a game-changer in our collective fight to protect our climate and prevent pollution in the Chesapeake Bay by preventing organic waste from ending up in landfills, incinerators or being land-applied raw,” Kreloff added. “Anaerobic digestion reduces greenhouse emissions for cleaner air, averts runoff that endangers the ecosystems of our waterways and generates a source of clean, renewable energy.”

Going west

On the other coast, Divert broke ground Sept. 7 on its Integrated Diversion and Energy facility

in Longview, Wash.

The 66,000-square-foot facility will be able to process 100,000 tons of food scraps into natural gas using anaerobic digestion annually after it comes on-line at the end of 2024.

Divert has an interconnection agreement with Cascade Natural Gas, which will allow the natural gas produced at the facility to go into the existing distribution pipeline.

“This facility represents the first wholly new clean technology and clean manufacturing-focused facility approved under the State’s stringent environmental protection framework (SEPA) in Southwest Washington in the last decade,” according to a fact sheet from the company.

The facility will help retail food customers, agricultural food producers, industrial food manufacturers, local jurisdictions, restaurants and others comply with Washington’s HB 1799, which requires large food generators to divert food from landfills. The facility is also close to Portland, Ore., which has its own diversion policy.

Washington Senator Maria Cantwell said the Divert project is “exactly what we had in mind when we got the expansion of the clean energy tax credit in the Inflation Reduction Act.”

The $100 million facility is the first project in development since Divert made a $1 billion infrastructure development agreement with Enbridge earlier this year. It also brings Divert closer to its goal of having 30 facilities across the U.S., within 100 miles of 80% of the population, by 2031.

Divert currently operates 10 facilities across the U.S. and works with nearly 5,400 retail stores to process more than 2.3 billion pounds of food scraps.