This article appeared in the March 2023 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

Recycling is a multi-step process, and the most important step is the initial separation of recyclables from the trash. This may seem like an easy task, but for many individuals and for multiple reasons, it can be surprisingly difficult. As a result, where, how and on whom we should focus our efforts to improve recycling become challenging questions.

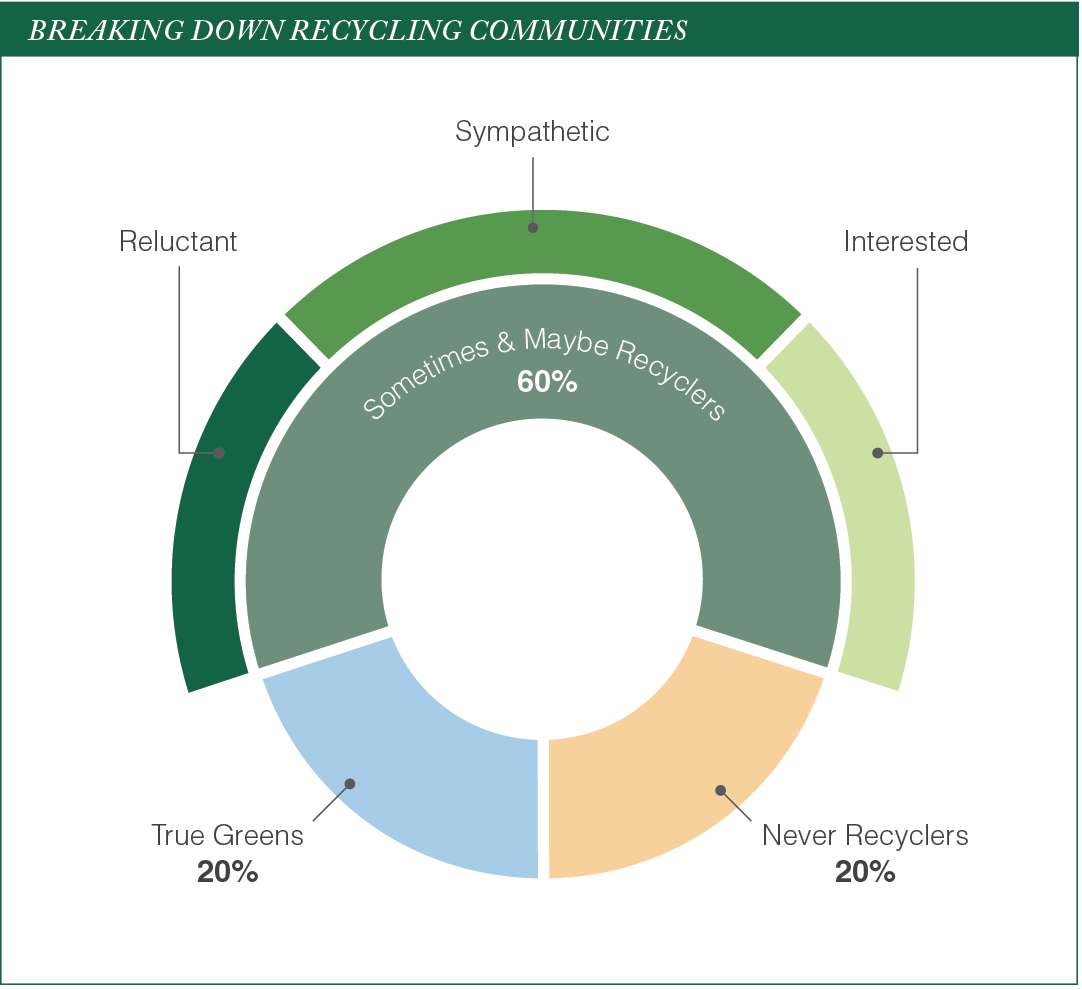

The 20-60-20 framework

To help guide the development of a recycling plan, we can look to the 20-60-20 framework to identify three broad categories of recyclers in a typical community and their relative proportions: True Greens (20%), Sometimes and Maybe Recyclers (60%) and Never Recyclers (20%).

The actual ratio of these categories will differ across communities based on several factors – recycling costs, community norms, age/quality of recycling infrastructure, political support and local history of environmental support – but we can use the 20-60-20 framework as a starting point for understanding recycling behavior.

True Greens

The True Green category is made up of avid recyclers – those who have made a personal commitment to recycle right. These individuals will try to recycle no matter how hard, complicated or inconvenient it is. True Greens need only information and directions as to how, where and when to recycle and will lead the charge in their communities. They actively engage in other pro-environment behaviors and generally want to do the right thing.

Sometimes and Maybe Recyclers

This category has varying degrees of interest in recycling and motivation to participate in it. They generally support environmental protection and are willing to engage in pro-environment behaviors, but only under the right conditions. Sometimes and Maybe Recyclers fall under three broadly defined and overlapping subcategories:

Interested: These individuals are inclined toward recycling, but they need it to be convenient and easy to do. Information must be easy for them to obtain and understand, and the recycling process must not require too much effort. This sub-group is more easily swayed by social norms (e.g., neighborhood participation rate).

Sympathetic: These individuals know that recycling is the socially desirable action, but they are more likely to act if there is an economic incentive. Recycling should be convenient, but sufficient economic incentives can overcome inconvenience.

Reluctant: These individuals are personally ambivalent about the environmental benefits of recycling but accept that it is a socially preferred act. They will recycle only if it is convenient and there is a sufficient economic incentive to make it worth their effort.

Never Recyclers

This category is made up of those who are highly unlikely to recycle under any scenario for a variety of reasons. These include physical challenges, insufficient storage space, anti-authority views and a lack of support for environmental protection. For this group, economic incentives and convenience are unlikely to overcome personal or structural barriers.

The implications

If we accept the general premise of the 20-60-20 framework, one of the most important implications is that the True Greens are a relatively easy audience to reach, but the largest and most important group to reach is the Sometimes and Maybe Recyclers. This last factor provides guidance on how recycling plans should be developed and where, when and how education and outreach are to be conducted.

Traditionally, education and outreach have formed the primary basis of many plans, which have relied on the distribution of “how to” information. The assumption is that providing the information will result in the desired action.

While knowledge about a community’s program has been found to correlate with recycling, this approach has its limits, as evidenced by lower-than-desirable recycling rates in spite of communitywide education and outreach campaigns.

If we accept the premise of the 20-60-20 framework, relying on information and knowledge alone will only work with the True Greens. Thus, while knowledge is essential, it is insufficient for reaching the largest target category.

Another key implication of the framework is that no significant effort should be expended to specifically target the Never Recyclers because the marginal cost will always exceed the marginal benefit. In other words, any time or resources expended on this group will always be greater than the resulting increase in their recycling.

Thus, the most important takeaway from the 20-60-20 framework is that we should focus our efforts on the Sometimes and Maybe Recyclers because these efforts will have the greatest potential for a return on investment.

However, outreach campaigns targeted toward this group need to be well designed and implemented, based on the perspectives and motivations of the Sometimes and Maybe Recyclers. These efforts should be modeled after the basics of community-based social marketing and combined with incentive-based policy instruments. Most importantly, outreach campaigns should always highlight convenience and policies should follow through by increasing convenience.

Community-based social marketing

There have been several books and many articles written on community-based social marketing (CBSM), which is a powerful framework for improving recycling by combining social marketing and behavior tools.

One of the initial steps in developing a CBSM plan is to identify the barriers to and benefits of the desired action (e.g., recycling cardboard) and the barriers to and benefits of engaging in the competing action (e.g., placing cardboard in the trash).

Crucially, we must identify what the target audience perceives as barriers and incentives, not what we solid waste professionals believe they are.

Following the identification of the barriers and incentives, the goal is to design a program that decreases the barriers and increases the benefits of the desired action (recycling), while simultaneously increasing the barriers and decreasing the benefits of the competing action (not recycling).

This of course can be a delicate balancing act, because the wrong approach can drive people toward littering and illegal dumping, or even cause a community backlash.

There are many CBSM behavior tools that have been employed to overcome the barriers to increased recycling. A great source for these is the Community Based Social Marketing website (cbsm.com).

These tools include commitments, social norms, nudges, prompts, social diffusion and many more. While these behavior modification tools encourage a person to engage in the desired behavior, that person has to be supportive of the action.

Therefore, these tools may be effective with True Greens and many Sometimes and Maybe Recyclers, but they will likely have limited or no effect on Never Recyclers.

Effective policy instruments

Policies are potent mechanisms for modifying behavior to achieve a desired outcome. While they can be based on or connected to CBSM behavior modification tools, they are generally more formal and often are codified as part of a law, regulation or ordinance.

Thus, instead of relying on voluntary actions through education and outreach marketing, policy actions can include punitive or economic consequences for non-compliance. With recyc ling, the best policy actions include economic incentives that also increase convenience.

ling, the best policy actions include economic incentives that also increase convenience.

An obvious example of an economic incentive policy is beverage container deposit refund systems. These bottle bill laws create a clear financial incentive to recycle containers and they have been very successful.

States with deposit-refund programs generally recycle covered containers at more than double the rate of non-deposit refund states. Segregating, rinsing, collecting and returning containers is not convenient (recent innovations in this process are addressing this), yet the economic incentive of getting your money back is sufficient enough to overcome one of the greatest barriers to recycling – inconvenience.

In contrast, policy instruments can increase the inconvenience of a non-desirable action by, for example, requiring an opt-out of curbside recycling. Another example would be distributing single-use plastic items such as straws, condiment packets and lids by request only, which raises the bar of inconvenience required to use these items. While this approach does not specifically increase recycling per se, it seeks to reduce the amount of non-recycled materials.

Implications for EPR

Our current recycling system is highly dependent on the waste generator to properly separate recycling from the trash stream, but as previously mentioned, this is too complicated for many individuals. And, as noted above, in spite of the resources and time spent on education and outreach, the 20-60-20 framework suggests that there is an upper limit to the recycling rate – there is a point of diminishing returns for investing in more education and outreach.

Assuming this is true, there needs to be a major shift in strategy to reduce the burden of proper separation by generators and to increase the onus of “designing for recycling” onto producers through extended producer responsibility (EPR).

This shift should focus on making recycling easier by reducing knowledge requirements regarding what does and does not go into the recycling bin.

California, for example, is trying to address this with its recently passed law (SB 54), which focuses on what is recycled rather than what is recyclable. The law includes a provision that by 2032, 65% of packaging must be recycled after use. It also mandates increasing the post-consumer recycled content of plastic packaging.

Strategies for plastics could include using fewer resin identification codes (RICs), using only those RICs with markets and/or reducing the use of mixed RICs in the same product.

Regardless of the approach, as the 20-60-20 framework highlights, the separation action of the customer will need to be made as simple and convenient as possible, with minimal education and outreach needs.

Moving forward

The 20-60-20 framework is a useful tool for improving our understanding of the general motivations and likely recycling interests and actions of individuals in our communities. To be sure, communities are different and may have unique characteristics, but they will all have these major categories.

By looking at communities through the lens of the 20-60-20 framework, we can see that outreach efforts are best directed at the biggest and most malleable group: the Sometimes and Maybe Recyclers. If we communicate with these residents, and make recycling easy and convenient for them, we will yield the best possible improvement to our overall recycling rate.

Travis Wagner is a professor emeritus at the University of Southern Maine and currently a solid waste consultant based in Sonoma, Calif. He can be contacted at [email protected].

This article appeared in the March 2023 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.