This article appeared in the August 2022 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

At the height of its aluminum can recycling efforts, Reynolds Aluminum Recycling Company (RARCO) had more than 1,000 employees and almost 700 locations in cities and towns across the United States where the public could bring in aluminum beverage cans for cash.

These buyback locations took many forms, taking in material via trailers, service centers and certain Reynolds plants. RARCO was a core component of Reynolds’ recycling and reclamation division, which operated from the late-1960s to 1998 and carried out the nation’s first closed-loop business model for post-consumer packaging.

RARCO’s buyback efforts yielded impressive results. There were years when RARCO collected more aluminum from its buybacks than Reynolds Metals used to produce aluminum beverage can sheet and beverage cans. The program went from collecting 1 million pounds of aluminum in its first year to an apex in the late-1980s, when it brought in more than 300 million pounds annually. Today, that would equate to more than 10.2 billion individual aluminum beverage cans.

Recently, the aluminum beverage can industry, via the Can Manufacturers Institute (CMI), announced ambitious U.S. recycling rate targets. These involve building from a strong base as the most recycled beverage container in the United States according to The Aluminum Association, and growing 2020’s 45% recycling rate to 70% by 2030, 80% by 2040 and ultimately 90% by 2050.

The lessons learned from the buyback locations operated by RARCO offer a blueprint for an impactful way to obtain more used beverage cans (UBC) for recycling.

How it started

Reynold Metals CEO David Reynolds had big ideas about recycling. First, in the mid-60’s, he commissioned a study that found buyback sites might be good locations for capturing more aluminum to recycle into can sheet. He then gave Dick Bolling, an industrial engineer who served as the first general manager of RARCO, $1 million to turn the idea into a reality. This was new territory for the company for several reasons, namely that it was the only part of the company to directly interface with consumers.

Bolling and some of his colleagues formed a recycling group in the 1970s to manage the buyback network, which eventually became RARCO. The unit was separate from the mill products division, which sold the aluminum beverage can sheet that was made into new cans.

Senior Vice President Paul Murphy saw growth in recycling as an incredible sales tool for aluminum cans. At one point, Murphy directed his team to open a buyback location in Minnesota even though few beverage cans were consumed in the area because he wanted Minnesotans to wish they had more aluminum beverage cans.

As RARCO further developed, a new group of leaders emerged. “Legendary recycling pioneers” like the late Steve Thompson and Andy McCutcheon were part of that charge. RARCO leaders included Charles Rayfield, general manager; Tom Draney, national operations manager; and Michael Timpane, area business manager.

Staff from CMI, which represents U.S. metal can manufacturers and their suppliers, spoke virtually with these three former employees in March 2022 for an interview on the Reynolds buyback network. Most of the details and anecdotes in this story were provided during that interview.

The buyback network

Buyback locations were placed all over the country. Some were in big cities like Atlanta, Miami, Seattle, Los Angeles and Washington, D.C. Others were in smaller cities and rural areas. According to Draney, rural areas performed best. In fact, one outpost in Raleigh, N.C., collected more than 20 million pounds of aluminum in one year.

Many factors went into the success of these locations. The first was operating in places where people need supplemental income, so there would be a strong recycling ethic and/or community support (e.g., schools, families).

Second, RARCO positioned itself to stand out in high-visibility areas. This was a challenge because some communities did not want trailers parked at “nice” shopping centers or other sites where they might be considered distracting, an eyesore or a cause of increased traffic. They tried to make their trailers prominent with clean and simple signage as well as a unique, eye-catching paint job consisting of pure white with red and blue.

Third, the team provided convenient access. One center in Florida was incredibly successful, but business slowed when they were forced to move the trailer across a canal, making it harder for customers to get to. It picked up again when they were able to move the trailer back near its original location.

The final key to success was hiring local personnel with ties to the community, pride in recycling and the appropriate skill and salesmanship to operate and work the trailer. To ensure excellent customer service, Reynolds even sent secret shoppers to sites to collect feedback on the experience.

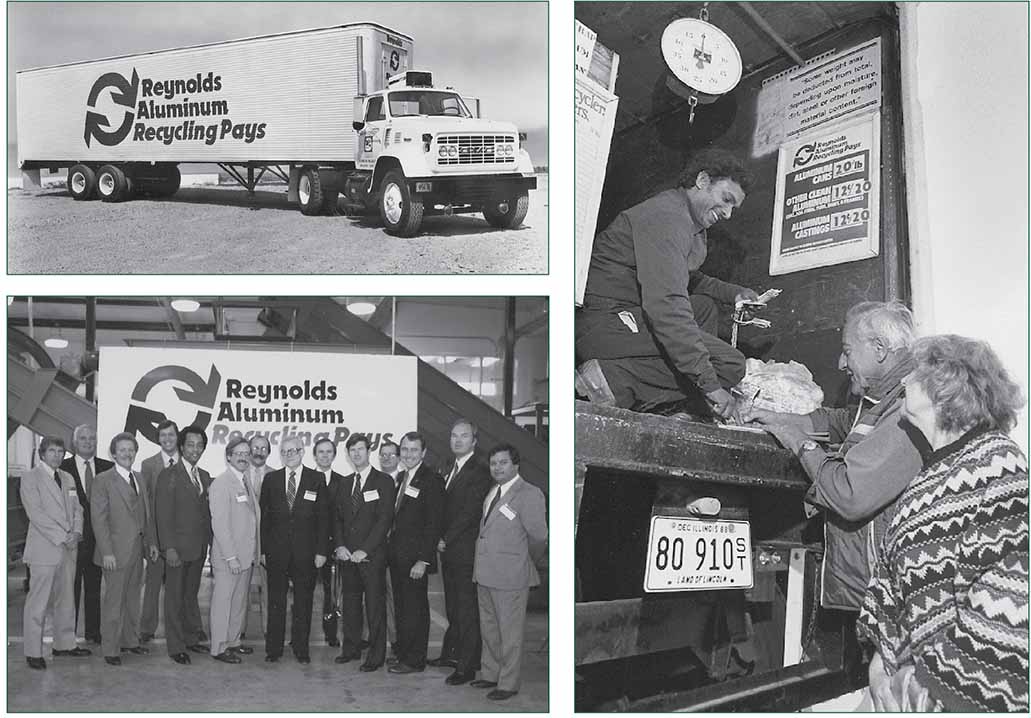

Scenes from an aluminum buyback program run by Reynolds Aluminum Recycling Company (RARCO) from the late- 1960s to the late- ’90s.

Buyback operations

Before opening a trailer, RARCO would typically prepare a market plan with the appropriate strategy and tactics. The program began to grow more quickly as they created routes for the trailers, often hitting five or more locations in a week. After some practice, it was much easier to know where to park the trailers because they could compare which sites worked best.

The trailers would remain in a given location if it proved to be an effective one, resulting in operators taking more responsibility and treating it like their own business.

The trailers accepted UBCs and other non-ferrous material until they couldn’t fit any more in a trailer or until there was no one else in line. “On most Saturdays, the lines at many of our facilities were out to the street, like Chick-Fil-A,” said Timpane. RARCO would buy cans from any customer with at least one pound of cans, which today is the equivalent of about 34 cans.

All kinds of people came to sell their cans to Reynolds; one minute a pickup truck would drive in to drop off a bunch of bags full of cans, the next minute it was a Mercedes with a couple pounds of cans. Professional football player Jack “Hacksaw” Reynolds (no known relation) even came in with his daughter and a very dense bag of cans that felt like a solid piece of aluminum. He claimed to have crushed the cans when his team lost a game.

People brought in cans to sell for different reasons. Some were environmentally conscious, others wanted the extra income and others simply did not want to waste something that could be repurposed. In one instance in Florida, people turned in cans for cash because they wanted to provide a local school with the funding it needed to run its air conditioning.

As the program became more successful, Reynolds hired an advertising firm called The Martin Agency and many public relations professionals to help them grow their customer base. The PR push included targeted coupon programs and in-person media blitzes to raise public awareness. RARCO had the PR firms meet annually in-person to share best practices so they could learn from each other and apply the campaigns in other areas of the country that had worked best. The use of professional marketers helped them run their operations like retail businesses, even conducting focus groups to determine optimal driving distances and price points to motivate people to bring in cans for cash. A significant portion of the marketing budget was spent on a nationwide toll-free number that people could call to find their nearest buyback center.

The buyback location operators knew it was important to win the support of nearby businesses. They did that by demonstrating that buybacks would drive up sales. For example, operators gave out $2 bills and Susan B. Anthony dollars as payment since they were relatively unique. Then, when customers used them to buy things at local stores, those stores would make the connection to the buyback locations and determine they were good for business.

In addition to the trailers, RARCO also bought cans from customers at service centers and densifying plants. The large-volume, permanent service centers were often converted gas stations on a busy corner where people could take their cans to get cash. Service centers were a key part of their operations as trailers often only provided about half of the aluminum volume that RARCO recovered and service centers provided most of the rest. There were also dozens of densifying plants where RARCO baled or shredded the cans and where people could bring their UBCs for payment.

It was all one big reverse distribution system. The UBCs from the trailers would often go to a service center. There, the cans would typically be flattened and loaded into a trailer where they would be taken to a processing plant to be shredded for melting. Then the material would go to a mill to be melted down and made into new aluminum cans. Each step in the network had increased quality and contamination control and steps to increase density, thereby reducing freight costs.

The network’s eventual demise

Most of the company did not expect RARCO to last long. This sentiment was due to the company focusing more on profit and loss rather than ancillary benefits like spreading awareness of Reynolds Metals and consumers feeling good about purchasing more cans knowing this recycling effort was in operation.

However, the program endured for many years. As it continued, RARCO’s approach became more sophisticated. In the early days, operators would go to areas simply hoping many cans would be returned, but later efforts were much more targeted. RARCO became more strategic over time thanks to programs they developed that showed them exactly how many cans were being consumed in certain areas and why people were drinking them.

Thompson, one of the leaders at RARCO, drove the generation of these programs. Many aspects of these programs, such as consumer recycling behavior profiles, are still used in modern curbside program education efforts. He also spearheaded the creation of color-coded maps of the United States marking areas that would generate a positive return on the investment if a buyback location were to be placed there with the right operator and approach.

Other companies tried to emulate Reynolds and find ways to encourage more can redemption for cash. Alcoa focused on encouraging metal scrap dealers to accept UBCs. Anheuser-Busch (AB) was aggressive for many of the same years as RARCO, financing equipment like flatteners and balers to help independent scrap yards and other entities enter the can collection market. In certain areas of the country, AB rivaled Reynolds in terms of aluminum collected.

While RARCO’s work led to greater public awareness of recycling and a consistent supply of recycled material to put into its production process, it was not always profitable. Eventually, the champions of the recycling buyback effort were dispersed or retired. Wise Metals and TOMRA bought RARCO prior to when Reynolds Metals was sold to Alcoa in 2000. There are several locations that remain open today. After everything, former RARCO employees remain close and reunite periodically to rehash recycling stories.

Replicating the model today

Recycling is different today than when RARCO operated its buyback network, but the model could still see success in certain areas, particularly with UBC prices at such high levels. Buyback centers could incentivize can recycling and make it more readily available in areas that lack access. According to The Recycling Partnership’s 2020 State of Curbside Recycling report, 6% of U.S. households do not have access to recycling. These households are mostly in places where the buyback centers performed best: smaller cities and rural areas.

When asked about the model’s applicability today, former leaders at RARCO said it could be possible, but there would be challenges. For one, people still do not realize the value of the beverage cans they throw out. Also, it may be harder today to find a place to park the trailers. To enact such a program today, RARCO’s three former employees suggest doing it in areas where people would value the money, there’s a steady consumption of beverages in cans and there’s a lack of curbside recycling.

Bringing back the buyback network in some way could help achieve the aluminum beverage can recycling rate targets that CMI members set. Recognizing the potential increase in recycling that could come with increased collection of UBCs, CMI recently created cansforcash.com to help people find metal scrap yards near them that accept UBCs and access other information about how to redeem their cans.

Although its success peaked decades ago, Reynolds’ buyback network proves that local aluminum buyback sites can work. With some tweaks to the old design and siting in areas based on the success factors realized from the initial model, locations where consumers can turn in their UBCs for money could be a successful way to reach underserved communities and promote higher rates of aluminum beverage can recycling. This model and the story of the Reynolds buyback network is unique to aluminum beverage cans because of their relatively high economic value. The potential additional cans that could be recycled through locations that pay cash for cans is huge, and the history of the Reynolds buyback locations provides a blueprint on how to do it successfully.

Scott Breen is vice president of sustainability at the Can Manufacturers Institute and can be contacted at [email protected]. Lilly Hyde is a master’s in management graduate of Georgetown University’s McDonough School of Business. She can be contacted at [email protected].

This article appeared in the August 2022 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.