This article appeared in the May 2022 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

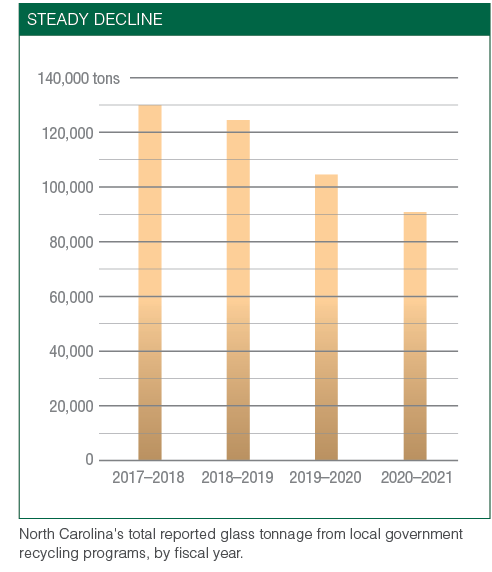

In North Carolina, the collection of glass for recycling has fallen by 30% in the past four years, a decline fueled in part by global commodities market shifts and the COVID-19 pandemic. To help meet the glass industry’s aggressive goals and align with economically beneficial end markets, North Carolina community recycling programs need to reverse the declining glass recovery trend across the state.

To help, the Recycling Program of the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) went to work, engaging stakeholders, developing strategies and best practices, and ultimately providing funding to cultivate an increase in the quality and quantity of glass collected in the Tarheel State.

Declining tonnages

Each summer, DEQ receives recycling tonnage reports from all 652 counties and municipalities in the state. These reports show that the state’s collected glass has fallen from 130,000 tons in the 2017-2018 fiscal year to 91,000 tons in 2020-21. This drop has occurred despite the robust end markets within the state: Ardagh, Owens-

Illinois, Sierra Nevada and Strategic Materials all have facilities operating in North Carolina that depend on cullet.

When China’s National Sword policy was enacted in 2018, many materials recovery facilities (MRFs), haulers and local governments felt the strain of falling prices for cardboard, mixed paper and mixed plastic. To compensate for higher costs and lower revenues, recycling processors raised tipping fees for all inbound loads. Additionally, many MRFs charged higher fees if customers had a large percentage of glass in their commingled mix.

North Carolina recycling officials frequently heard from MRF operators that glass was the most expensive material to collect, sort and transport because of its relatively high weight and its stress on equipment. Local governments that used these MRFs often had to choose between paying more or dropping glass from their list of accepted recyclables. Many local programs chose the latter, and the state’s MRFs have reported that the percentage of glass in the single-stream mix has decreased by 6% over the past three years.

North Carolina recycling officials frequently heard from MRF operators that glass was the most expensive material to collect, sort and transport because of its relatively high weight and its stress on equipment. Local governments that used these MRFs often had to choose between paying more or dropping glass from their list of accepted recyclables. Many local programs chose the latter, and the state’s MRFs have reported that the percentage of glass in the single-stream mix has decreased by 6% over the past three years.

Prior to National Sword and the pandemic, most areas in North Carolina had some sort of access to glass recycling, whether through drop-off sites or curbside programs. Some county drop-off programs collected glass separately, and only a few counties that were located far from a glass processor did not accept glass at all. However, due to the higher recycling processing costs, 46 local programs have taken glass out of their commingled mix or dropped it entirely. By comparison, recovery numbers for both plastic and paper have stabilized and grown since the start of the pandemic.

Several local governments that took glass out of their curbside programs have since set up glass-only drop-off sites as an alternative. With a combination of strong outreach and staffed sites, drop-off glass has low contamination; however, the tonnage recovered is lower when compared to the convenience of curbside collection.

MRF tools and hub-and-spoke

The Glass Packaging Institute (GPI), the trade association representing the glass container industry, recently announced that it aims to have 50% recycled content in all glass containers produced by 2030. They also stated their goal to achieve a 50% recycling rate for glass containers in the United States by the end of the decade. Currently, most glass containers are created with about 35% recycled content, and according to the U.S. EPA, the country’s glass recycling rate is just over 31%.

Clearly, the downturn in North Carolina collection is at odds with those industry aspirations. To address these challenges, DEQ identified two primary strategies to stabilize the tonnage of recycled glass in the state: improve glass cleaning equipment at MRFs and establish hub-and-spoke collection in certain regions. To better direct these efforts, DEQ convened a group of glass recycling stakeholders, which included Anheuser-Busch, Ardagh, the Glass Recycling Foundation (GRF)., GPI, Owens-Illinois, Sierra Nevada, the Southeast Recycling Market Development Council (SERDC) and Strategic Materials. This group emphasized the need to bring glass recycling back to communities that removed it entirely, noting this step would yield the most tonnage returning to the bottling industry.

Additionally, after touring multiple MRFs across the state, DEQ staff found some common occurrences in their processes that diminished the value of recycled glass.

In MRFs with inefficient glass cleaning equipment or no equipment at all, non-glass residue contaminated much of the glass pile. The piles contained bottle caps, bits of paper, and flecks of plastic. These types of contaminants behave similarly to shards of glass once they hit the MRF tipping floor. At these MRFs, non-glass residue made up more than a quarter of the glass stream, and tiny bits of glass under three-eighths of an inch (called fines) made up another 15%. Glass beneficiation facilities cannot recover such small pieces of cullet – MRFs with inefficient or non-existent cleaning equipment were shipping glass loads to processors that contained about 40% unusable material. Most often, the cost of hauling these glass shipments outweighed the revenue from the material’s sale.

However, the MRFs that operated newer, more efficient glass equipment experienced much less contamination in their glass piles. One MRF operated an organic separator to comb paper and plastic from its glass stream. Relatively inexpensive, this machinery reduced non-glass residue to 11%. As a result, the MRF operator received more favorable pricing when selling its cleaner glass to a processor.

Meanwhile, in analyzing the effectiveness of hub-and-spoke models for glass recycling, DEQ staff learned regions served by a specific MRF that does not include glass in commingled recycling can still provide glass recycling access through drop-off programs. In a hub-and-spoke model, the hub is a central location that has a concrete pad or a “bunker” to aggregate glass. The spoke communities are surrounding counties and municipalities that bring glass collected in roll-off containers to the central hub. From the aggregation site, haulers transport glass in bulk to a glass processor.

Local government recycling programs in regions not accepting glass in recycling could apply this model to efficiently provide source-separated recycling collection to residents, bars and restaurants.

In 2019, DEQ and GRF supported the development of a hub-and-spoke system in North Carolina’s Orange County. Orange County Solid Waste Management built a glass bunker to aggregate all the source-separated glass from the county’s recycling drop-off sites. DEQ and GRF provided grant funding and roll-off containers to the county. Two neighboring local governments – Durham County and Alamance County – also began bringing their source-separated, drop-off glass to the Orange County hub. Once the site amasses enough tonnage, county employees haul the collected glass 80 miles to Strategic Materials, a glass processor with a site in eastern North Carolina. Orange County did not charge the surrounding spoke communities a tipping fee; however, it kept all the revenue from selling the glass downstream.

A glass aggregation bunker in Orange County, North Carolina. The county is at the center of a new hub-and-spoke collection network.

From grant dollars to impact

As a result of the continued success of the Orange County project and the MRF glass tours, the state opened a glass-specific recycling grant round in October 2021. DEQ committed $200,000 to contribute to projects that support long-term access to glass recycling in the state. The grant stipulated applicants must be either a MRF or a local government that planned to expand or improve glass recycling in its region. Applicants also had to guarantee that any glass collected would be recycled into a new product, such as bottles or fiberglass.

With the goal to fund projects that would improve the quality and pricing of recovered cullet, the grant encourages communities to provide access to glass recycling long-term. Improved MRF equipment and new hub-and-spoke systems throughout the state would provide stability to glass recycling and eventually bring back lost tons.

After receiving proposals in early 2022, DEQ awarded five grants – to two MRFs and three to local governments.

The MRF projects will be at Sonoco Recycling’s MRF in Wilmington and at Mecklenburg County’s publicly owned MRF in Charlotte. Both projects will add new glass cleaning equipment to reduce the amount of non-glass residue in their glass streams, and both MRFs expect these upgrades will increase the value of their outbound glass.

The three local government projects will enhance or establish two hub-and-spoke systems. An existing glass recycling bunker in Moore County will use grant funds to expand its concrete pad. The city of Pinehurst will also receive funding to create its first glass drop-off site since taking the material out of curbside collection.

One new hub-and-spoke model will be in Pitt County, which recently removed glass from its commingled recycling. When its local MRF stopped accepting glass, Pitt County purchased a dozen roll-off containers to collect glass at their convenience centers. Once the concrete bunker is constructed, communities from outside the county will be able to bring source-separated, drop-off glass to Pitt County. Pitt County will also aggregate the glass from its own convenience sites and transport it in bulk to a glass processor instead of making more frequent, smaller hauls.

The GRF has also pledged to support the three local government hub-and-spoke projects with an additional investment of $35,000 to help cover project costs. With the GRF funding, the grant dollars committed from the state, and the matching funds from all five grantees, the total investment in glass recycling totals more than $600,000. Once completed, these projects will ensure the availability of long-term glass recycling to regions that serve more than 2 million North Carolinians.

“This effort demonstrates the power of public-private partnerships to ensure that the state’s recycling system supports a continued move towards a circular economy for glass,” said DEQ Secretary Elizabeth Biser.

The grant projects will be launched in the spring of 2022, and they will serve as examples of how communities and MRFs can reinstate glass recycling and shore up existing programs with cost-effective, regional solutions to stabilize and grow the glass recycling industry.

Optimism looking forward

Despite the falling tonnage of recycled glass in recent years, DEQ staff remains optimistic that strategic, regional investments will reverse the trend. Glass is a material with nearly total domestic end markets, and local government participation is crucial for it to remain a recycled material in perpetuity.

Matt James is an environmental specialist at the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality and can be contacted at [email protected].

This article appeared in the May 2022 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.