This article appeared in the March 2022 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

A lot of effort has been invested over the past 30-plus years to build waste diversion programs in institutional settings, including colleges and universities, corporate campuses, and government agencies. Even as the public-facing infrastructure for recycling and organics collection expands to match the scope of trash collections, ongoing struggles with contamination and lackluster participation suggest that access alone isn’t enough to achieve high recovery rates at institutions.

Efforts to educate people help, but there’s a growing understanding that part of the problem lies with the collection system itself, with building managers often simply grafting recycling onto a “legacy” collection arrangement designed simply to remove trash efficiently. This has resulted in bin infrastructure and service arrangements that ignore behavioral factors and passively, if not actively, encourage people to sort items incorrectly.

To truly advance materials recovery, institutions need to rethink their collection programs from the ground up. Recognizing this, a growing number of organizations are embracing steps such as redesigning waste bins, using strategic bin placement patterns, adapting the role of custodians and even shifting more responsibility for handling waste to individuals.

The realities of human behavior

The structural barriers against public-facing recycling and organics recovery start with a defining characteristic of most legacy collection systems: the ubiquitous network of trash bins. Spread throughout building corridors, campus pathways, meeting rooms and individual workstations, the standard practice has been to distribute trash receptacles far and wide to maximize convenience.

Outdated perceptions of trash as the default service and diversion as “nice-but-not-essential” mean this pattern of bin placements and the corresponding service go unquestioned. As a result, diversion efforts face high capital and operational costs to catch up to this infrastructure. The conventional thought is to add a recycle bin next to every single trash bin in order to capture discarded recyclables rather than evaluating if a bin is needed in an area at all. Even where diversion infrastructure and service levels catch up to trash, diversion efforts are frequently seen as a separate and optional redundancy when budgets are tightened.

An equal but less understood barrier is that much of these legacy arrangements are rooted in a one-dimensional understanding of behavior. What’s complicated about slapping a recycling label on a bin and telling people to toss their bottles into it? The problem, of course, is that neither people nor the recycling process are that straightforward.

Readers of this journal don’t need a primer on recycling’s complexities. But even among industry professionals there’s been a steep learning curve to appreciate the extent to which the intricacies of a program’s design influences recycling behavior. People often want to recycle, but they don’t want to spend a lot of time thinking about it – and figuring out what goes where can oftentimes require a degree of attention many don’t have to spare.

Without fully appreciating this fact, simply adding a recycling bin next to the trash is an invitation to contamination.

Trend toward redesign

Acknowledging those realities, a growing number of public and private organizations are stepping back to redesign waste collection systems that are more in tune with behavior patterns. Some of these steps are in fact decades old but are getting renewed attention.

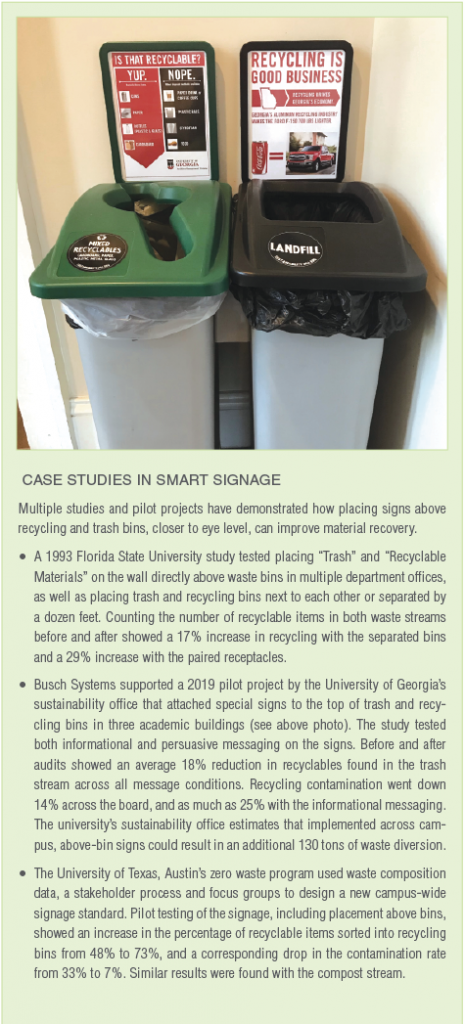

Understanding that people may not look at a label, program designers are emphasizing color distinction between bins, eye-level signage and other visual cues that prompt quick recognition of the separate streams. Waste composition data can also be used to better craft signage, calling out commonly confused items.

Without strategic coordination, large institutions over time add successive generations of bin styles with often random colors and features. Additionally, lists of acceptable materials can differ between buildings on a campus, not to mention the surrounding community. The market turmoil caused by contamination has created an urgency to designate and codify uniform bin and branding standards so people aren’t expected to constantly refamiliarize themselves with how to sort items.

This trend received a big boost from California’s 2016 SB 1383 legislation, which officially designates using the color blue for recycling, green for organics and black for trash. More sophisticated zero waste programs like Arizona State University’s extend these color standards to the back-of-house system of bag liners, custodial carts and compactors to minimize confusion among collection workers.

Infrastructure can be redesigned to actually guide sorting behavior. A 2015 Keep America Beautiful (KAB) study documented how replacing the traditional office deskside waste basket with a smaller bucket clipped to the side of a regular-size recycling basket increased the recovery of recyclables and reduced contamination by close to 20%. Among other reasons cited, the study observed that it was simply easier for distracted office workers to drop a sheet of paper into the larger recycling bucket than to force it into the 7-inch-wide trash bucket. Microsoft, the Bank of Nova Scotia and the University of Michigan are among the hundreds of organizations that have found success with some version of this system.

Embracing centralized collections

A more fundamental step gaining attention is the shift toward centralized collection arrangements. If the traditional model is to place bins anywhere someone might use them, centralized systems ask people to carry waste items a few extra steps to use a smaller number of centrally located bin stations.

The concept can be applied in several ways. Waste baskets can be removed from classrooms and meeting rooms with the expectation that people take items to the larger hallway bins as they leave. Many organizations that have adopted the small-trash, regular-recycling basket system for workstations have simultaneously discontinued deskside custodial service and instructed office workers to carry all waste to the centralized bins. Some corporate offices have eliminated individual deskside baskets altogether.

Taking the strategy outside, the University of Maryland, University of British Columbia and Yale University are among many campuses that have studied foot traffic and other usage patterns to remove, in some cases, hundreds of unnecessary trash bins along pathways and open spaces.

These arrangements frequently encounter initial resistance from office workers or predictions of increased litter from custodial and grounds workers. But experience shows the sky does not, in fact, fall. People adapt to a new routine, and with careful planning, litter rates do not go up.

What these redesigned arrangements do result in is cost savings around labor and other areas. Eliminating redundant outdoor trash bins avoids the cost of buying new recycling bins to pair with them. The small clip-on deskside trash buckets don’t require bag liners, potentially saving tens of thousands of dollars. And though more research is needed to document the impact, the anecdotal experience of many sustainability managers is that centralized collection arrangements often result in higher and cleaner materials recovery.

Impact of COVID

These best practice trends come at a time of COVID-19 and upheaval for many waste diversion programs.

Custodial and collection staff labor shortages have left many organizations scrambling to empty bins, even as reduced occupancy has caused a decrease in total waste volumes. The pandemic has also caused a shift to more single-use disposable items and an increase in PPE (masks and gloves), paper towels and disinfecting wipes. The reduction in occupancy also means less people generating food waste and recyclables, which has lowered total diversion rates for many organizations.

Additionally, the pandemic has opened opportunities to reevaluate programs, improving signage and removing unnecessary containers so that when people return to the site, the efforts are refreshed. While changes to legacy arrangements often generate resistance, COVID’s stress on custodial labor and the need to reduce touchpoints has provided compelling cover to push forward. Greater tolerance for disruption and remote working have allowed managers to implement new systems and redesign bins and signage so that people return to an established “new normal” (see the feature “Put to the Test” in the May 2021 issue of Resource Recycling).

Systems thinking

Centralized collections and similar arrangements acknowledge that waste management is more than a simple operation – it’s a system like energy or traffic management. By taking an analytical approach and rethinking basic practices, waste collections can be improved to deliver efficiencies and better material recovery.

While the recycling industry has rightly invested in new education to address contamination, greater priority is needed to promote infrastructure best practices that also improve participation. Advocates of these practices have for years encountered institutional resistance, in part because of a lack of hard evidence they could deliver on promises. To address this, more investment is needed in proof-of-concept research, like the KAB deskside study, which has had a catalytic effect driving acceptance of the small-trash basket concept.

Looking beyond the institutional sector, local and state jurisdictions can expand on California’s lead promoting uniform color and messaging standards that reduce confusion.

Finally, sustainability professionals need to forcefully push back against institutional inertia that treats waste recovery as a box to check rather than a system that can be optimized to deliver greater value.

Alec Cooley is senior advisor at waste and recycling container provider Busch Systems and can be contacted at [email protected]. Amy Marpman is sustainability director at janitorial and soft services provider SBM Management and can be contacted at [email protected].

This article appeared in the March 2022 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.