The authors lay out different approaches to goal setting and measurement for EPR programs. | Skylines/Shutterstock

One of the major differences in producer responsibility policies relates to how outcomes are prescribed – e.g., collection and recycling targets, accessibility and other requirements. This third article of a four-part series on producer responsibility policies will explore the impacts associated with how outcomes are set.

The purpose of producer responsibility policies has generally evolved. In Canada, producer responsibility policies, which include deposit return policies, were initially established with three main purposes: reduce litter, divert waste from landfill, and reduce costs to municipal governments.

These initial policies focused on collection rates as a primary means to measure the success of these policies. While many of the above purposes remain relevant, governments are increasingly broadening the outcomes they seek to achieve, including reducing waste, increasing access to recycling, improving product/packaging design, reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, and ensuring materials are actually recycled into new products.

There are three main questions that are generally asked in the development of producer responsibility policies: What needs to be measured? Who should be responsible for setting these targets? And how should they be measured?

What needs to be measured

The first key question is what needs to be measured to ensure the outcomes sought in the policy are achieved. Depending on the outcomes sought, these targets will be different. They may include:

- Collection targets, which measure performance based on the amount of designated material that was collected. This is one of the most common targets in producer responsibility requirements. These targets can be difficult to establish if the designated materials are supposed to be consumed (e.g., paint).

- Management or recycling targets, which measure the amount of material collected that was properly managed. For some materials that are toxic or hazardous in nature (e.g., needles or pharmaceuticals), this may simply be to ensure they were properly disposed of; for other materials, it may mean they are recycled or diverted from landfill.

- Accessibility targets, which measure the accessibility of collection to consumers (e.g., based on population density) or potentially they could be measured based on what is done to ensure the public is aware of the ability for designated materials to be properly managed. These targets are often included to ensure that policies do not create situations where materials are only collected from dense urban areas.

- Product design targets. Some jurisdictions have begun to include performance requirements that measure waste reduction, recycled content use, or other factors related to life-cycle analysis. As an example, Belgium currently requires larger producers every three years to prepare, submit and publicly report on reduction/reuse plans.

- GHG reduction targets. Some jurisdictions are also requiring reporting to show how GHG emissions generated by collecting and processing materials are being considered in an effort to reduce emissions. As an example, Saskatchewan requires producers to undertake the research and develop a data tracking and modeling system for GHG emissions associated with collection and recycling activities.

There is certainly an argument to be made that governments are overextending what producer responsibility policies can achieve, and by complicating the intended outcomes could create problems. The concern is the more performance measures that are added, the more you may confuse the intended outcome. Product design requirements may potentially impact the ability to collect and process materials.

Producer responsibility does not need to tackle every issue when other policy mechanisms may be far more effective at driving outcomes (e.g., minimum requirements for recycled content, virgin extraction taxes, or carbon pricing policies). While it may be politically expedient to have a catch-all policy, it will not necessarily be effective.

Many concerns are being raised in Ontario as recent producer responsibility policies allow producers to reduce their management requirements through the use of recycled content. For electronics, management targets can be reduced for manufacturing warranties or if repair tools and parts are provided free or at cost. The concern is not that these are not worthy initiatives to support but that the approach could complicate the process and reduce the amount of materials captured and processed.

Who is responsible in setting targets

There are two main approaches to establishing targets: Either they are established by the government or they are established by the producers through a program plan. One approach is an outcomes-based approach and the other is a process-based approach.

The process-based approach is the most prominent model in Canada. Producers are required to develop a plan based on consultations, and those consultations must include targets and how producers plan to meet those targets. The government approves these plans. Plans often provide more confidence to the government, because they remove uncertainty. However, they also allow for ongoing interference and generally reduce opportunities for innovation.

In an outcomes-based approach, the government sets the targets and allows producers greater flexibility in how those targets are met. This approach relies more heavily on ensuring the targets are set appropriately. This is the approach Ontario and Quebec are taking and is being looked at carefully by a number of other provinces.

How are targets measured

The way targets are measured is extremely important. Comparison of various producer responsibility policies is often done without explaining the differences in how measurements are completed. There are a number of considerations, including the following:

- How specific are targets, and

- How keywords are defined and measured.

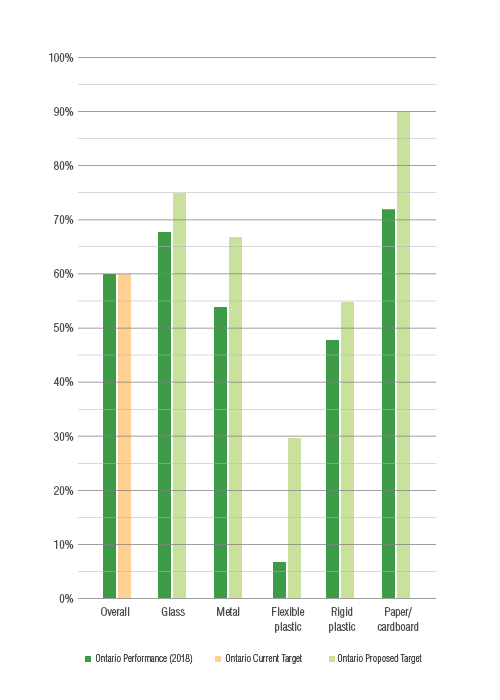

Ontario’s recycling target for paper products and packaging is a basket-of-goods approach with a single target established for all materials. Because the target is broad-based, it allows for poor-performing materials to be ignored. As a result, based on the latest data, while certain materials have high recycling rates (e.g., paper is 72%, glass is 68%), other materials such as flexible plastics have recycling rates under 10% (see chart below for details). The more specific the targets are, the greater the ability to address materials that may be difficult to collect and/or recycle. Many jurisdictions have begun to set more specific packaging targets that focus on the material stream (e.g., paper, rigid plastic, flexible plastic, metal, glass) and/or specific packaging formats (e.g., beverage containers).

The more specific the targets are, the greater the ability to address materials that may be difficult to collect and/or recycle. Many jurisdictions have begun to set more specific packaging targets that focus on the material stream (e.g., paper, rigid plastic, flexible plastic, metal, glass) and/or specific packaging formats (e.g., beverage containers).

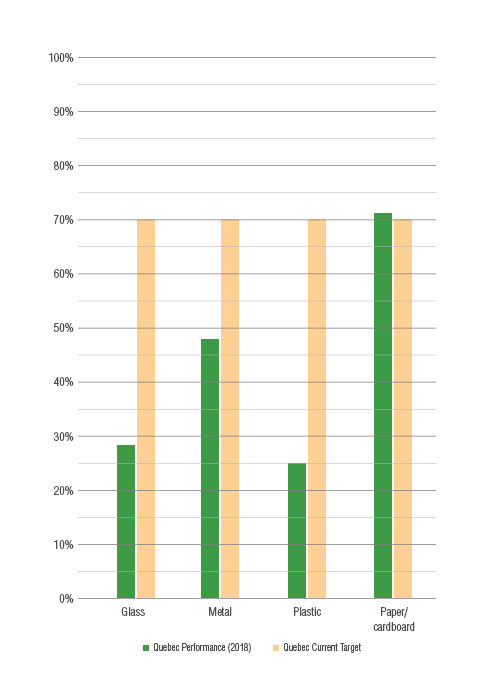

In Quebec, recycling targets are set based on specific materials (e.g., paper, cardboard, plastic, glass and metal). The recycling target for each of these materials is set at 70% and despite these targets being in place for decades, the performance for plastics and glass remains under 30% (see graphic below for details).

Because Quebec uses a shared-responsibility model, there are no substantive consequences for underperformance. The issue of enforcement will be addressed in greater detail in our final article of this series.

Because Quebec uses a shared-responsibility model, there are no substantive consequences for underperformance. The issue of enforcement will be addressed in greater detail in our final article of this series.

Targets also require establishing definitions. The definition of recycling varies as to whether it includes backfill (e.g., aggregate replacement), energy recovery or the production of fuels. Given issues with material markets, there is a general trend toward definitions that require reporting on material processed, net of residual. The Canadian Standards Association’s guideline for the accountable management of end-of-life materials uses this definition, as does the European Union.

Recycling is also often measured very differently. Sometimes recycling is measured based on what was collected, and sometimes it is based on material that is marketed. The European Union is taking it a step further by defining it based on the amount of material actually recycled, which excludes all contamination.

Most jurisdictions establish targets based on weight (or units, as is the case with beverage deposit systems) because this is the most practical method of measurement. Producers must report on the total weight of materials they supply into the market (i.e., denominator). Performance of the program is measured based on the total material collected over the total material supplied. This can be more difficult to measure for products that are used for longer, such as tires and electronics, or where changes in product composition have been significant. It can, however, be overcome through the use of rolling averages. Some jurisdictions have chosen other factors like per-capita weight collected. This can be problematic because it is not necessarily a good indicator of what might be available to collect.

Governments often spend more time worrying that targets are set too high rather than too low; however, there are far more issues created if targets are set too low. The targets are what force investments in design, collection and processing infrastructure. If set too low, the status quo continues, and any innovation is hindered. If set too high, companies might not meet targets but are unlikely to be penalized if they prove they are making progressive strides to achieving the established targets.

Editor’s note: The first part of this series (an overview of extended producer responsibility policies) can be found here. The second part (focused on system costs) can be found here.

Pierre Benabidès is from Lichens Recyclability and Peter Hargreave is from Policy Integrity Inc.

More stories about EPR/stewardship

- CAA publishes revised Colorado program plan

- WM outlines investments in recycling infrastructure

- ‘Operational readiness is high’ as Oregon rolls out EPR