This article appeared in the October 2020 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

Many communities face the challenge of shouldering the significant financial burden of implementing a recycling program and are in need of support of a local city, county or regional government to help provide funding.

To help local governments manage best practices for forging a partnership, industry group The Recycling Partnership with assistance from Burns & McDonnell developed a “Guide to Community Materials Recovery Facility Contracts.” The resource aims to help local recycling programs navigate a materials recovery facility (MRF) contract to define standards and spell out tips for sustainable program implementation. The contract between a local recycling program and a MRF is one of the most impactful legal documents in the U.S. public recycling system, addressing financial and service provisions.

The contract guide is designed to assist public recycling programs and MRFs develop transparent, balanced recycling processing contracts. This allows each party to navigate volatile market conditions and an ever-changing landscape of consumer packaging. Community recycling programs and MRFs have distinct needs, but they also share common ground in promoting recycling in communities. To achieve and implement a sustainable recycling partnership, local programs and MRFs should approach contracting as a partnership benefiting all stakeholders involved.

The August 2020 edition of Resource Recycling included an article written by Scott Mouw of The Recycling Partnership that provided an overview of the contract guide. This second article provides additional insight into the MRF contracting process.

Importance of developing a strategic approach

The need for a recycling contract guide dates back to the 2008 financial crisis.

Prior to 2008, many recycling processing agreements included relatively low per-ton processing fees, typically in the range of $30-$40 per ton. MRF operators were willing to charge lower upfront fees in exchange for the MRF keeping a higher percentage of the commodity sales revenue. While recyclable materials are commodities, with constantly fluctuating values, in October 2008 values plummeted from all-time highs to all-time lows in a matter of weeks.

With nearly 79% of U.S. cities contracting for recycling processing services, it is critical for MRFs and local governments to have long-term, sustainable contracting approaches in place. The 2008 financial crisis sparked a decade-long transformation in recycling processing contracts: In general, more risk was placed on local governments in the form of higher upfront per-ton processing fees; MRFs, meanwhile, became increasingly willing to share more of the revenue from the sale of materials.

Since 2008, multiple other issues have impacted the need for more sustainable recycling processing contracts. With constantly changing material packaging and increased contamination levels, the need to focus on the quality of incoming materials has become critical. Furthermore, commodity values have been constantly fluctuating due to a range of factors, including oil and gas prices and production levels, material export bans and tariffs, and facility capacity shifts. There is a great need to have positive relationships between local governments and MRFs to strengthen recycling initiatives in the U.S. The strongest MRF processing contract is one that clearly recognizes, protects and fairly accounts for the interests of both sides involved.

An ideal MRF contract allows all parties involved to adapt to a range of market conditions and create shared financial risks and rewards. Additionally, it establishes strong communication to prevent confusion. For instance, the contract might set clear expectations around acceptable recyclable materials and lay out plans on how to manage costly contamination issues.

So how to start putting the pieces together for a successful contract? Prior to initiating the MRF contracting process, local governments will significantly benefit from evaluating their options and developing their procurement strategy.

Get aligned from the start

At the outset, city planners should strive to accomplish two things: Identify goals and objectives, and find synergy between bids and contracts.

Before beginning a MRF procurement and contracting process, a local program should take time to consider and decide what it wants to accomplish with the contract and what it needs for the contract to deliver. A local program should take into consideration all angles that could affect a community, including political, operational, financial and legal perspectives.

Community stakeholders may have different views of what is important in a MRF contract, but ultimately the varying perspectives need to be put in alignment. Issues such as inviting competition, choosing the optimal contract length, allowing for possible renewals, deciding whether and how much material revenue is important and determining acceptable MRF performance standards are all important details that allow a community to be comfortable with its MRF contract.

Bid procedures, meanwhile, eventually lead to finished contracts. The design of request for proposal (RFP) or request for bids (RFB) documents should anticipate the development of mirrored contract clauses that reflect the accepted proposal or bid.

In other words, procurement and contracting are two sides of the same coin and there should be tight alignment between the two in terms of structure, language and expectations.

Types of MRF contracts

Prior to initiating the RFP process, communities need to research and decide what type of recyclable processing contract agreement best meets their needs.

One common approach is called a processing services agreement, or PSA.

In this agreement, a local government contracts with a recycling company that owns and operates a facility at a location owned or leased by the company. Currently, this is the most common approach used by U.S. local governments for the processing of their communities’ recyclables.

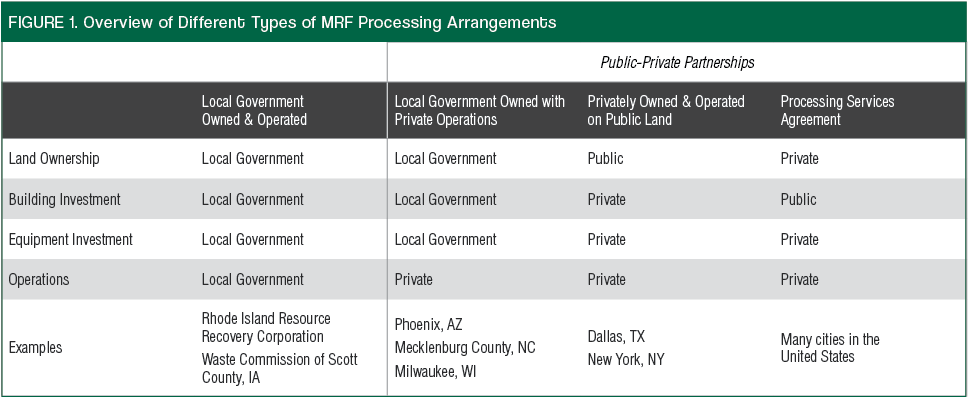

Another approach is a public-private partnership, or P3.

In a P3, a local government and private recycling company collaborate to co-invest and share resources, such as land and capital investment in equipment. With some P3 agreements, the public entity owns the facility and contracts with a private entity to operate it.

As laid out in Figure 1 above, there are wide variations in the configuration of P3 relationships, including situations where the public entity owns the land, the building, and/or the equipment. But regardless of the ownership arrangement, a private recycling company is typically responsible for operating the MRF.

Starting the contract process

Local governments usually require a competitive procurement process to enter into a contract with a private recycling company. Considering that a MRF processing contract can last for multiple years and involve millions of dollars, completing a procurement process requires careful planning and multiple steps.

First, the local government develops the RFP. In doing so, the municipality considers its goals and objectives and reflects them in the document, looking ahead to how the RFP elements will translate into the final contract. A contract’s terms and conditions should also be included when issuing an RFP to streamline contract negotiation and keep both parties on the same page with expectations.

From there, MRF companies will develop and submit proposals. Proposers develop their submittals, with opportunities to have questions answered in writing or during a pre-proposal meeting.

Next, the local government evaluates, negotiates and awards the contract. A technical and financial review of proposals is conducted, often involving interviews of prospective companies. Contract negotiations commence and a formal award is made. This step may include an evaluation of hauling expenses to the various MRFs to see the full picture of the costs associated with each option.

Finally, there will be the transition and implementation of the contract. Timelines and steps are followed to implement the agreement. The level of effort and time needed for this step can vary widely. When a MRF is in place and has available capacity, the transition may just be a matter of directing collection vehicles to a different MRF. In cases where a new MRF must be constructed, transition and implementation efforts are much more involved, which impacts the schedule.

Scheduling success

A key factor in determining how much time is needed for the procurement process depends on the competitiveness of the local recycling processing market and processing capacity in that region.

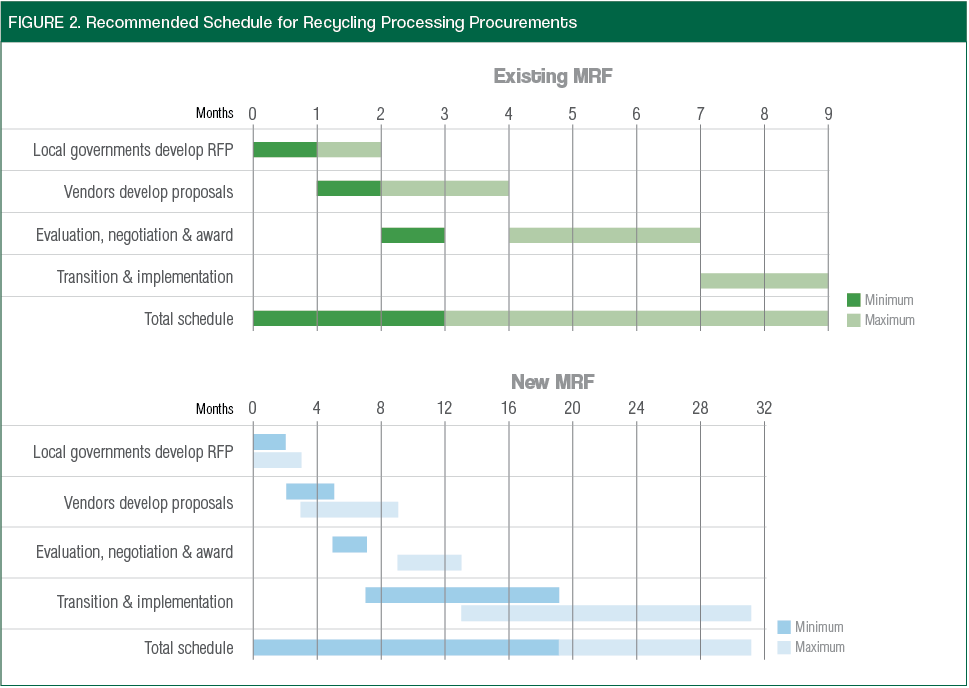

For example, if there are multiple MRFs in a region with extra processing capacity, the procurement process will require less time since a range of possible suitable MRFs are already in place. On the other hand, if there is a need to build a new MRF based on the outcome of the procurement process, much more time would be required to allow the MRF operator to design, build and start operating a new facility, or potentially build a transfer station to transport the material to a MRF. Figure 2 above provides perspective on recommended schedules based on whether a local government would expect to enter into a contract with an existing and/or new MRF and based on what type of contractual agreement a community chooses.

Also on the topic of timing: It is extremely important for the community to make strong and thoughtful decisions on the length of its MRF processing services contract. Decisions on contract length can have a significant effect on how many proposals or bids may be submitted and how competitive they are.

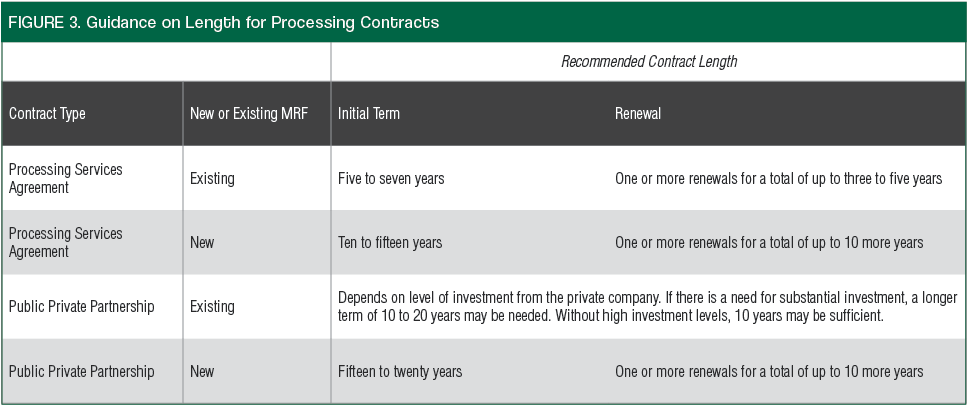

Several factors determine the optimal recycling processing contract length, but perhaps the most important factors are the type of contractual arrangement – PSA or P3 – and whether a private company is building a new facility. New, state-of-the-art MRFs built to serve large geographic areas can cost $20 million or more, depending on local development costs and the level of processing automation.

If a private company is building a new MRF for either a P3 or PSA, the company will ideally seek to recover its capital costs over the life of the contract. Consequently, aligning contract length to the useful life of capital assets can help local governments and the private recycling processor achieve a lower cost.

Ideally, contract length allows MRFs adequate time for a return on investment but does not preclude market choice over time. Short-term contracts could be self-limiting to municipalities if they result in a disincentive for MRFs to make capital investments that improve processing effectiveness and efficiency.

The ideal length of a contract can vary based on whether it’s for a PSA or P3 project and whether an existing or new MRF is involved or not. Figure 3 (below) provides recommended length of time for contract terms.

Fitting community needs

Many communities benefit from using a consulting services firm in developing their bid processes and documents. Consultants can bring broad experience in addressing this critical issue and are able to use ready language, document structures and procedures from their work with other communities in guiding what can be a complex procurement process. Consultants may also have industry relationships that can attract potential bidders to an opportunity, increasing options for the local government.

Regardless of the exact approach a community uses, local officials should take the time to understand the realities in recycling markets and to clearly identify local goals and objectives.

Scott Pasternak is the lead co-author of the “Guide to Community Materials Recovery Facility Contracts.” He advises local and regional governmental clients on their solid waste and recycling procurement and contracting issues, as well as related planning, operational and financial consulting services. He can be contacted at [email protected].

Learn how Burns & McDonnell can support your community in developing recycling programs by visiting burnsmcd.com/services/environmental/solid-waste–resource-recovery.