This article originally appeared in the August 2019 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

The waste trade world is a murky one, with few people involved on the collection side having any real idea where many of the materials from their local programs end up. We’ve all become accustomed to throwing our discards away, but elaborate chains of custody often make it impossible to know where “away” actually is.

That fact is all too evident on the outskirts of Surabaya, Indonesia.

Since China enacted its National Sword campaign at the start of 2018, the world has become increasingly aware that bales of mixed plastics have caused pollution and human health concerns in many pockets of Asia. But in Surabaya, a port city of 3 million inhabitants on the Indian Ocean, problematic plastics are arriving in a different manner: as contamination in paper bales.

In the past year, as China has decreased its appetite for recycled fiber, Indonesian imports of the material have skyrocketed – for instance, U.S. shipments of scrap paper to Indonesia grew from 484,00 short tons in 2017 to 1.28 million short tons last year, according to the U.S. Commerce Department.

Though classified in the permitting process as paper, the bales have levels of plastic contamination as high as 60%, according to analysis by local environmental group Ecoton Indonesia. Recently, Indonesian officials unveiled import guidelines to try to cut down on the contamination issue. But their final specs were dialed back from the country’s initial 0.5% contamination proposal, which is the threshold that has been instituted by China and some other countries that are serious about cleaning up their recycling sectors.

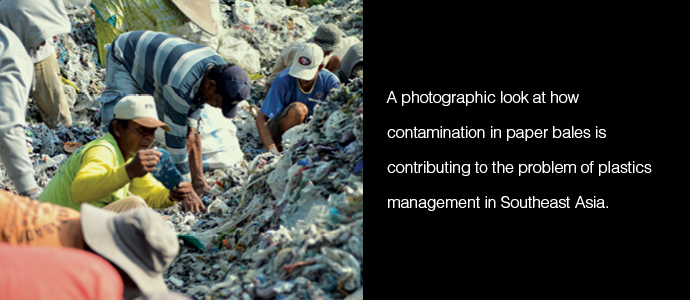

There are nearly a dozen paper factories in the area of Surabaya I recently visited filming a feature-length documentary called “The Story of Plastic,” which is due out this fall. It became clear that environmental standards for materials processing are non-existent here. The plastic scrap separated from the paper is openly dumped in the villages surrounding the paper manufacturing sites, and waste pickers go through the piles looking for anything of value.

The photos below show the reality on the ground in this Southeast Asian manufacturing zone. Surabaya shows us what “away” really looks like – and why the global waste and recycling system can no longer ignore it.

A massive industrial zone outside Surabaya, Indonesia includes companies involved in all manner of manufacturing and light recycling. Paper factories there are surrounded by rice fields and villages. Plastic scrap, separated from fiber bales, is openly dumped in these villages, and waste pickers go through the material looking for polymers of value.

Individuals sorting through the plastic fields work six days a week, only stopping for the call to daily prayers. They operate in loose collectives, making about $1.50 a day per person.

Any given site can see up to 10 trucks per day discarding material, and there are hundreds of sites all around the area. The pickers look for HDPE, flattened PET and aluminum. Sometimes, they find something else: foreign currency that somehow made it into a paper bale.

Villages surrounding mosques are completely inundated by plastic scrap, so much so that one can’t see the ground. In some places, even roads and sidewalks are covered.

Waste pickers in Surabaya are experts on scrap commodity pricing, with a keen understanding of what is worth collecting at any given time. They test polymer types by lighting material and smelling the smoke. Because the stream of incoming material is constant, it only makes economic sense to collect the resins with the most value.

Near the paper manufacturing sites are hundreds of small tofu factories, where plastic scrap has replaced wood as the primary source of fuel to boil water for making the food products. Workers shovel plastic pouches and other packaging into small furnaces used to heat water. Other workers shovel the ash straight out the back door, forming a new set of waste piles.

Activists around the world are waging a war on plastic, working to ban problematic materials. But with the increase in packaging coming down the pipe, it’s hard to imagine what will come of an already-saturated system. For starters, serious regulation on exports needs to be established to stop the flow of waste from rich countries to poor. In addition, haulers need to pay attention to where the stuff they collect is going. With virgin polymer prices so low compared with recycled resins, regulations like mandating high thresholds of recycled content in new products would also help immensely to improve the margins of recycling companies and attract venture capital into domestic recycling systems in countries around the world.

What’s clear is that as a global society, we are already past the point of reckoning, and if nothing is done, and done fast, we’re looking at a future we can’t even imagine. There is too much plastic in the system, and until we peak production and decline, the situation will only grow worse.

Stiv Wilson is the director of campaigns at nongovernmental organization The Story of Stuff Project. He is executive producer of the group’s “The Story of Plastic” documentary. He can be contacted at [email protected].