This article appeared in the January 2019 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

The landfills in Calgary, Alberta are the quietest they’ve been in decades. The amount of garbage processed at the city’s three landfills fell from a record 750,000 metric tons in 2014 to 460,000 metric tons in 2017. Numbers for 2018 suggest that the trend is continuing.

Does that mean that Calgary has figured out waste management policy? Is it on the path toward a “circular economy”?

As so often is the case in waste management, the truth is more complex. Calgary has made progress, but it also faces ongoing challenges. For instance, though Calgary’s diversion rate has steadily increased, the city has encountered waste-related funding shortfalls and stockpiled recyclables.

Ultimately, the situation in Calgary highlights a broader lesson: Improving waste systems isn’t just about reducing waste disposal; instead, it’s about making systems deliver more benefits at lower costs (including both the financial and environmental sides of the ledger).

A new report called “Cutting the Waste” from Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission – an independent think tank made up of policy-minded economists – argues that governments should place their focus not necessarily on higher recycling rates but on improving the overall efficiency of our waste management systems. Doing so requires waste and recycling managers to consider the full range of costs and benefits associated with potential policy changes.

And perhaps the greatest strategy to drive more efficiency in waste is allowing our systems to operate more like true markets.

The story from one city

To understand the nuances of waste and recycling efficiency – or lack thereof – let’s dig into the details around Calgary’s efforts. The city has gradually built up its waste diversion services, including the addition of curbside recycling in 2009 and organics collection in 2018. Together, these programs have pushed residential diversion rates from 16 percent in 2008 to 35 percent in 2017. And with the organics program now fully implemented, the city estimates its diversion rate is set to climb to around 60 percent.

At the same time, however, high tip fees at Calgary’s city-owned landfills are pushing haulers to truck locally collected waste to disposal sites with cheaper rates, and these locations can sometimes be as far as 180 miles away. Data from 2016 indicates as many as 300,000 metric tons of Calgary’s waste was shipped elsewhere, which certainly explains some of the drop in volume at Calgary’s own landfills. This reality has also caused Calgary landfill revenues to fall significantly, forcing worker layoffs and reducing the hours of operation at its landfills.

What’s more, Chinese import restrictions on recyclables have hit Calgary hard. For months, the city was forced to stockpile recyclables that no longer had a market. And the materials that are sold now fetch lower prices due to a global glut in materials. Meanwhile , Calgary’s privately operated materials recovery facility is spending more money to meet tighter contamination standards required by buyers today. Even with the ongoing growth in local diversion programs, the city will likely struggle to hit its 2025 diversion target of 70 percent.

Calgary’s challenges will sound familiar to waste program managers elsewhere. Governments across the continent – in municipalities, states and provinces – have in recent years committed to waste diversion targets that are difficult to achieve and sustain. And the rapid changes in recycling markets have made these targets even more elusive.

Waste management programs have also become more expensive. On the garbage side, it is costly to operate and maintain landfills – and to build new ones when existing sites reach capacity. One reason for this is that environmental regulations for landfills are more stringent and increase expenses for operators. Land is also scarce, particularly in urban areas, forcing cities and site operators to either truck waste over greater distances or build new landfills closer to residents’ backyards.

Waste diversion is a clear solution but is also growing more expensive in many cases. In Canada, for example, the costs of diverting residential waste have increased at a much faster rate than the amount of processed materials. At times, the cost of collecting, sorting and processing recyclables exceeds the value on global markets, and recycling technologies are still developing and costly to deploy. Meanwhile, consumers expect better and more comprehensive recycling and composting options.

Roadmap toward efficiency

So how exactly should public officials and others move forward on these economic issues that are bigger than any one player?

The Ecofiscal Commission’s report argues that the best way to improve efficiency is to make waste management systems work more like well-functioning markets. Markets are generally very good at efficiently allocating resources on their own.

Rather than governments determining how much of a good or service producers should supply, or how much consumers should buy, markets – and market prices – let individuals choose how to best satisfy their own preferences.

It is this flexibility that can drive greater efficiency in waste management. It allows waste generators and waste managers to decide whether it makes more sense for them to take their waste to the landfill, or whether to look for cheaper alternatives, like recycling and composting. Market prices, in other words, can guide us toward a more economically efficient balance between different waste management options.

Currently, however, waste management systems in most regions are not guided by normal, well-functioning markets. Prices for waste management, where they exist at all, do not typically reflect the full costs and benefits associated with waste management services and materials. These structural problems may, for example, help explain why North Americans generate so much waste and why most of it gets landfilled.

To better explain why waste systems are inefficient, our report identifies six interconnected problems that cascade through the solid waste chain. Addressing each of them represents an opportunity to improve the performance and efficiency of our waste management systems using market-based approaches.

1. Most households don’t pay directly for waste management

Households typically pay for waste collection through property taxes or monthly fees. In other words, the amount residents or businesses pay for waste management often has no connection with the quantity or composition of solid waste they generate. As a result, households tend to generate and dispose of more solid waste than they otherwise would if they paid directly for the service. This reality also weakens the incentive to recycle, compost and reduce waste.

2. Landfills do not charge large waste generators the full cost of disposal

Tip fees at landfills make waste disposal more transparent for large waste generators. However, in many cases in Canada and the U.S., the fee for disposing every ton of garbage is less than the full cost of managing it. The result is artificially cheap waste disposal, which discourages waste prevention and diversion.

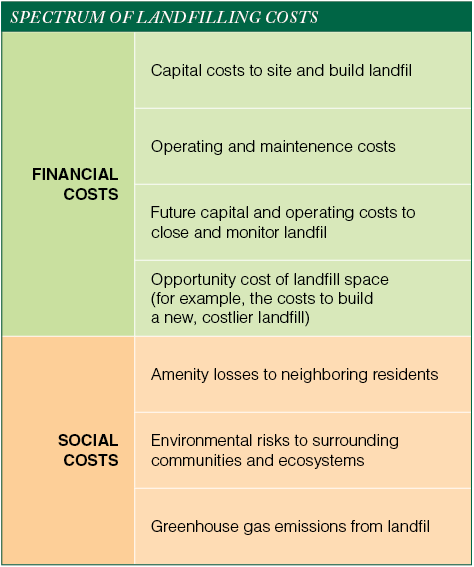

Although most landfills charge tipping fees that cover basic operating costs, fewer include the full range of capital costs needed to build, maintain and upgrade infrastructure (see figure below). Even fewer charge fees that reflect the “opportunity cost” of landfill space. This cost reflects the fact that capacity is finite at a given landfill – each additional ton of material hastens the time that a community will need to find a new and often costlier alternative.

3. The boundaries of waste management systems are porous

As the Calgary case study demonstrates, if a municipality increases tip fees to more closely reflect the full cost of disposal, haulers may start taking their loads elsewhere. The mere threat of this occurring may encourage municipalities to keep rates artificially cheap. While waste shipments across a region aren’t necessarily a problem in and of themselves, they do cause cost complications for municipalities. Building and maintaining landfills is capital intensive, and a large portion of the costs are fixed. When waste exports increase, municipalities generate less revenue to cover these costs.

Waste shipments can also undermine environmental outcomes if garbage is sent to landfills that have weaker environmental performance or to systems that put less emphasis on resource recovery.

4. Some important factors for diversion success are outside the control of local officials

Even if communities address the three issues noted above, there is still a reliance on downstream buyers for diverted material. Collection and management systems for diversion often make financial sense only when operated on a broader scale. Achieving this scale can be difficult, particularly in small, rural communities.

Also, operators have limited control over how waste is sorted before they collect it, relying on households and businesses to do it correctly. As has been widely discussed in the industry, despite better education and awareness, contamination rates are at 25 percent or higher for residential loads in many municipalities, increasing processing costs and reducing the value of diverted materials.

5. Municipal pricing policies have limited effect on goods manufacturers

If waste management services were priced according to their full cost – in all jurisdictions – consumers would have clear incentives to purchase goods made with less packaging or from more easily recyclable materials. Producers, in turn, would have incentives to design and manufacture goods that generate less waste.

But even if individual municipalities charged residents the full cost of waste disposal, these price signals would have a negligible impact on upstream production. Waste is priced locally, and even a coordinated rate-setting effort among a collection of municipalities would not be enough to affect the choices made by global manufacturers.

6. Environmental externalities from using virgin materials are not factored in

Most consumer goods use virgin materials extracted and processed from the natural environment. These processes, however, can cause significant environmental problems, such as greenhouse gas emissions and air and water pollution, that are currently unpriced or underpriced in global markets. This effectively subsidizes the use of virgin materials; product makers have an incentive to use more virgin materials and fewer recycled and reused materials in their manufacturing processes.

Tangible steps to square the economic equation

Policies that address the six issues above can make our waste markets work better, improving their overall performance and efficiency. To this end, our report lays out several recommendations for governments.

Efficient waste management starts with charging tipping fees that reflect the full cost of disposal, including both private and social costs. Given North America’s heavy reliance on waste disposal, tipping fees are a benchmark for the entire waste management system and change the relative cost of waste diversion and prevention. Correcting price signals at disposal facilities can encourage the private sector to provide innovative and low-cost waste diversion opportunities.

Calgary has made significant progress on this front. The city doubled its tip fees between 2008 and 2017. The current fees cover operating, maintenance and capital costs, but they also include the future costs required to close and monitor the landfills once they’ve reached capacity. More recently, the city started charging higher fees for organics, cardboard and other recyclables. This approach, known as differentiated tipping fees, is emerging as an industry best practice.

But unless all landfills charge rates that reflect the full costs of disposal, waste shipments to other disposal sites could continue to undermine cost recovery in some municipalities. For this issue, municipalities could consider charging an additional fee on waste shipped to other jurisdictions to cover the local system’s fixed costs. Metro Vancouver in British Columbia implemented this policy in 2018, calling it a “generator levy.”

A second pillar of efficient waste disposal is pay-as-you-throw (PAYT) pricing, a strategy that creates a direct link between how much garbage households produce and how much they pay. In some communities, residents pre-purchase tags for each bag of garbage; in other areas, households are charged based on the volume of their garbage bin.

Evidence from across North America illustrates that PAYT can generate significant benefits. Natick, Mass., for example, has cut garbage volumes by 40 percent and saved the town $3.5 million in disposal costs since rolling out its program. Similarly, a PAYT program in Beaconsfield, Quebec cut waste by 50 percent, and about 80 percent of residents now pay less for waste collection.

Although PAYT programs are more common in the U.S. than in Canada, both countries have room to improve. The most recent Canadian survey on the subject, from 2005, found that fewer than 200 municipalities (about 5 percent) were employing PAYT. Several municipalities in Canada, including Calgary, are currently considering a switch to the pricing format.

The key role of extended producer responsibility

Tipping fees and PAYT programs are necessary but insufficient steps for creating truly efficient waste management systems.

Multiple policies are needed to address multiple problems. In particular, extended producer responsibility (EPR) policies can play a key role.

EPR programs make manufacturers directly responsible (both physically and financially) for managing the waste generated from their products. Designed well, they can provide market-based incentives that push manufacturers to make products with fewer materials or from materials that are easier to recycle. They can also help level the playing field: Such programs – implemented at the state or provincial level – establish higher waste diversion standards that apply across all waste systems within a jurisdiction.

Several Canadian provinces are making good progress on expanding and reforming EPR programs. British Columbia and Quebec have the most mature programs, spanning over 20 material types. The program in British Columbia for curbside recycling materials, for example, is 100 percent funded and operated by manufacturers. Municipalities in the province are no longer on the hook for running these programs and selling materials on global markets.

Progress in other parts of North America has been slower. Alberta is now the only province in Canada with no EPR programs, meaning that recycling costs are still downloaded onto municipalities like Calgary. Regulated EPR programs for printed paper and packaging are even less common in the U.S., although states such as Massachusetts and California are exploring the option.

Keeping costs in check

Municipalities face serious challenges in how they manage ever-growing quantities of solid waste. The six inefficiencies we have identified in waste markets apply in all communities, though to varying extents. Many struggle to meet ambitious waste management targets while simultaneously keeping down costs. The porous nature of waste systems makes the task even harder, as better disposal policies in one municipality can drive waste to jurisdictions with policies that are more lax.

Making our waste systems work more like well-functioning markets provides a clear solution. Tip fees, PAYT programs and EPR initiatives are all flexible, market-based policies that when well-designed, can reduce costs for governments, taxpayers and the environment.

See our full report for more details.

Jonathan Arnold is a senior research associate with Canada’s Ecofiscal Commission. Previously, he was an economist with Environment Canada’s Regulatory Analysis and Valuation Division in Quebec, working on industry air pollution regulations. He can be reached at [email protected]. Find the group’s “Cutting the Waste” report at ecofiscal.ca/reports.