In Vancouver, British Columbia, private-sector backing for recycling collection has freed up resources to tackle ambitious initiatives from local leaders.

In Vancouver, British Columbia, private-sector backing for recycling collection has freed up resources to tackle ambitious initiatives from local leaders.

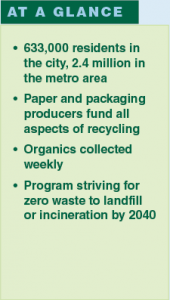

Vancouver is Canada’s third-largest city, with a population of about 633,000 in the city itself and about 2.4 million residents in the metro area. The city’s recycling program has undergone a major change in recent years as British Columbia has shifted to an extended producer responsibility (EPR) funding system.

“What that means is that producers, the companies that produce the packaging and paper products that end up in the recycling stream in British Columbia, are now responsible for delivering and financing those programs,” said Monica Kosmak, senior project manager for zero waste for Vancouver.

Legislation spurs shift

For years, Vancouver city crews collected recyclables curbside from the city’s roughly 110,000 single-family, duplex, triplex and fourplex households. For larger multi-family properties, collection was handled half by city crews and half by contracted private haulers. The private hauling presence was focused in the downtown core, where high rises dominate.

All residential properties were on a source-separation system, in which the paper stream was kept separate.

In spring 2014, however, the EPR system was implemented in the province. It is a full producer responsibility model, Kosmak explained. That means industry is fully responsible for the delivery and financing of the recycling program.

“That’s a lot of responsibility, but it’s also an opportunity, because it gives them the control to design an effective and efficient system that meets their needs,” she said.

Recycle BC, a nonprofit industry association, operates the EPR program. It has about 1,100 member companies, Kosmak said. Recycle BC develops a plan that has to meet the EPR regulatory requirements, but the framework allows the organization flexibility in how it goes about fulfilling its obligations. The provincial government approves the plan.

Recycle BC contracts out both collection and processing activities. Collection is contracted out to municipalities, meaning they are collecting on behalf of and being funded by the industry group. The industry group also performs sorting and marketing of the collected materials.

“This has created huge opportunities, because they do it for the whole province, so it’s created an economy of scale,” Kosmak said.

Also, because of sorting abilities at local facilities, the program is able to accept coffee cups, cartons, ice cream tubs and other polycoat cartons, spiral-wound containers and more.

“There’s been a real benefit for having this kind of industry innovation,” Kosmak said.

The program is funded by industry-paid fees. In 2017, this pot of money totaled 86 million Canadian dollars ($65 million). Companies generally recoup this money through a cost internalization model in which the recycling cost is included in the price the consumer pays for the product. Typically, Kosmak said, it’s less than 1 Canadian cent per product.

Handing over reins on collection

As the EPR switch took effect in 2014, the city considered whether to act as a contractor collecting materials and getting paid by Recycle BC, or to turn collection service over to the EPR group entirely. In the beginning, the city chose the contracting route, collecting recyclables and delivering them to Recycle BC for sorting and marketing.

But in October 2016, the city decided to shift gears and transition recycling collection service over to Recycle BC.

The city’s multi-family collection contract was set to expire without a renewal option, and the municipal collection fleet was aging and needed to be replaced at a cost of 15 million Canadian dollars.

The city’s multi-family collection contract was set to expire without a renewal option, and the municipal collection fleet was aging and needed to be replaced at a cost of 15 million Canadian dollars.

There was also a gap between Recycle BC’s funding obligation, which was set at 8 million Canadian dollars per year in Vancouver, and the actual cost for the city to run the program, which was 12 million Canadian dollars. And that gap was set to increase over time.

“That was something we could no longer justify, because if Recycle BC took it over, our residents wouldn’t have to pay anything,” Kosmak said.

The city ultimately divested of its recycling services and began transitioning collection service to Recycle BC. The industry group contracts collection service with a local hauling company.

The city has seen a number of benefits from transitioning over to Recycle BC-managed collection. The financial burden for managing collection was relieved. In addition, the department was able to redirect staff and resources from recycling into other programs and expand services in litter, abandoned waste and street cleaning collection.

In addition, municipal officials no longer have to spend so much time worrying about the effects of global shifts on commodity values.

“We were shielded from, and are shielded from, the market risks and volatility caused by China’s restrictions,” Kosmak explained.

Switching has also improved diversion. Recycle BC is statutorily required to recover a minimum of 75 percent of the packaging produced across the province.

“They have achieved a 92 percent recycling rate of what they collect, and our residents have enjoyed more services,” Kosmak said.

Pushing beyond recycling

Although it has achieved substantial recycling success, Vancouver is taking a more holistic view of environmental progress in the coming years.

“We can’t recycle our way out of this waste – that’s our perspective as a city as well as our stakeholders and residents,” Kosmak said.

So Vancouver in 2011 adopted a “Greenest City 2020” action plan, which includes a number of initiatives to reach a zero waste goal. For instance, the city has a target to reduce waste sent to landfill and incineration by 50 percent by 2020, compared with 2008 levels.

Earlier this year, the Vancouver City Council adopted a further goal of sending zero waste to landfill or incineration by 2040. This goal is structured around four focus sectors for waste reduction: food, products and packaging, buildings, and residuals.

To reach these goals, the city has made some changes to how services are provided. On food waste, for instance, organics have been collected since 2010 in various forms, but to advance the zero waste goals, the city in 2013 doubled the frequency of organics collection from every-other-week to weekly and reduced garbage frequency to every-other-week.

But despite the progress, the city is continuing to look for ways to advance its diversion efforts. If the city stopped tackling new initiatives and kept up its existing programs, from population growth alone the city would be sending 659,000 metric tons of waste for disposal by 2040, far more than the waste volume back in 2008.

“Our philosophy is that as population grows, we have to get more efficient with our resources,” Kosmak said. “We can’t allow for growth of waste. We have to actually reduce [and generate] exponentially less.”

This article originally appeared in the December 2018 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

Think your local program should be featured in this space? Send a note to [email protected].