This article originally appeared in the December 2018 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

At face value, the business model for a materials recovery facility is simple.

MRFs take in commingled recyclables, separate them, and then sell the sorted materials to buyers who process and transform them into new products. The new products are sold to consumers, and the process begins again.

In reality, though, the MRF business is much more complex, and challenges exist at many points. Material coming in the door may be highly contaminated, new forms of packaging may appear in the material stream, or commodity values may drop suddenly. This is why Closed Loop Fund is focused on understanding what it takes to operate and sustain a successful MRF, and disseminating what we learn.

Here, we discuss the biggest challenges to MRF profitability and explain how leading MRFs across the country are overcoming these struggles. We believe that a successful MRF must tackle all of these issues because they are all intertwined and contribute to a MRF’s ability to process and market raw materials cost-effectively.

Leverage vertically integrated business models

Success in finding resale markets for sorted commodities relies, in large part, on having clean, high-quality materials. MRFs can take steps to control both the type and quality of their incoming material stream before sorting and cleaning technology even comes into play.

MRFs typically rely on private haulers or municipal sanitation departments for their incoming stream and, in many cases, negotiate long-term agreements to accept recycling at a fixed price per ton. This seems like it would create stability for the MRF, but in reality, it means that a MRF has no guarantee of what it will receive, which is particularly challenging as ever-evolving consumer products find their way into recycling carts.

However, MRFs that are vertically integrated to include materials collections will have more control and predictability in their incoming commodity streams. With support from municipal and community partners, they can also take steps to educate (and re-educate) their collections customers in an effort to reduce contamination at the source.

A good example of this is Lakeshore Recycling Systems, a company that serves greater Chicago and northern Illinois with residential and commercial collections, single-stream recycling and construction and demolition (C&D) processing services.

Lakeshore’s Heartland facility processes more than 80,000 tons per year, almost half of which comes from Lakeshore’s hauling business. The rest of the material comes from third-party haulers.

Roughly one-quarter of Lakeshore’s revenues come from tip fees, which, per ton, are cheaper for haulers than local landfill tip fees.

Align contracts and incentives

Some MRFs own and operate landfills, which seems like a way to eliminate the cost of transportation and landfill tip fees for residue from the sortation process. In reality, though, this business model will almost always privilege landfilling as the cheaper option when compared with sorting and processing.

In essence, it’s easier for these operators to collect tip fees to dump material than it is to do a good job sorting it for material that has commodity value. And the sorting they do perform typically yields lower-quality bales of material that sell for a lower price.

To avoid the issue of conflicting business incentives, the most successful MRFs have created contracts with municipalities and waste haulers that incentivize landfill diversion, as well as higher-quality material. With these contracts, revenue from commodity sales is shared between the parties. This creates a common incentive to increase landfill diversion rates and reduce contamination because cleaner commodity bales command a higher price and more revenue for all. Regardless of operating model, municipalities have a significant role to play in shaping and aligning incentives with haulers and MRFs.

For instance, the Twin Cities area in Minnesota benefits from Eureka Recycling‘s services. A nonprofit social enterprise, Eureka holds the recycling contracts for residents of Minneapolis, St. Paul and other neighboring communities. Like Lakeshore, Eureka recovers nearly 100,000 tons per year of primarily residential recycling while maintaining a contamination rate below 10 percent.

The municipalities and other haulers bringing material to Eureka receive between 100 percent and 80 percent of revenue, depending on the contract, from commodity sales after Eureka’s processing cost is covered. As a result, the region has realized more than $2 million in economic benefit since Eureka completed an upgrade of its facility at the end of 2016.

Work to optimize equipment and workflow

Technology plays an important role in the success of every MRF. Workers picking material from a conveyor belt may not distinguish between polystyrene and polypropylene in a yogurt cup, but an optical sorter can.

Most MRFs have processing equipment that is optimized to sort for certain materials, but there are now frequent changes and trends in packaging, such as more pouches and less glass. As a result, there may be a mismatch between what the equipment is optimized for and what the MRF is receiving.

Upgrades to cutting-edge processing equipment are expensive and not to be done on a whim. But a MRF that analyzes its feedstock and residue and invests accordingly in appropriate technologies is likely to recognize financial benefits from increased resale volume. Of course, improved quality control can also come from people. The best MRFs are willing to experiment to achieve the right mix of labor and equipment and utilize technologies where needed to decrease contamination and improve the quality of their output.

For the Waste Commission of Scott County, Iowa, local labor provides much of its container sorting capacity. During peak volumes in the summer, this means that there is a bottleneck on the container line as staff picks through all the material the MRF takes in.

After adding a second shift last year, Scott County realized it was seeing even more material come in from the greater Quad Cities area in northwest Illinois and southwest Iowa and needed to relieve the pressure with an optical sorter. Although the necessary equipment is a significant investment, Scott County expects to make up the cost savings in labor in less than four years.

Grow customer relationships for market stability

On top of unpredictable input streams, MRFs also face unpredictable revenue streams. Commodities are often sold on a spot market, where demand and pricing is extremely volatile. This ongoing volatility is compounded by periodic shocks. One example is the decline in export markets as a result of China’s decreased imports of U.S. commodities beginning in 2017.

Furthermore, many MRFs work through brokers. In some cases, this intermediary can make it difficult to build direct, long-term relationships with customers who can provide forecasts about their future needs and feedback on the quality of the commodity. Together, these factors give MRF operators a feeling that they cannot safely plan or fundraise for investments in improving their equipment and technology.

Given that processing costs remain fairly stable at an average of $60 to $80 per ton, MRFs must find ways to exert more control over their end markets for all materials. Successful MRFs do this by developing strong ties with multiple customers for each type of commodity they sell. These relationships allow them to get feedback on the quality of their materials and to make continuous improvements. This continuous improvement and direct communication enables MRFs to sell their materials for the best possible price.

As noted, diversification of buyers is key, and in light of the changes in China’s import policies, having a mix of domestic and international buyers is important. MRFs with domestic customers will continue to have a home for their materials as the international market shifts and recalibrates.

As noted, diversification of buyers is key, and in light of the changes in China’s import policies, having a mix of domestic and international buyers is important. MRFs with domestic customers will continue to have a home for their materials as the international market shifts and recalibrates.

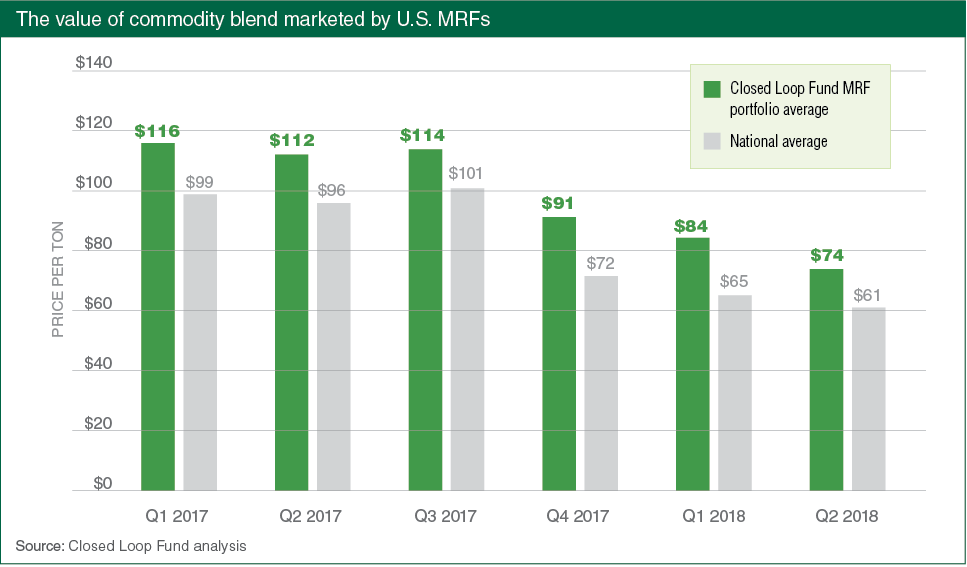

In the Midwest, Closed Loop has invested in MRFs in Chicago, Minneapolis-St. Paul, the Quad Cities and Omaha, Neb. By nature of geography, this region has never relied exclusively on export markets. At this moment, when MRFs and communities on the coasts are feeling the direct impact of China’s National Sword policies, best-in-class MRF operators like Lakeshore, Eureka and Scott County in the Midwest are weathering the storm. The basket value of their saleable single-stream commodities has averaged 15 percent to 25 percent above the national average prices on spot market in 2017 and 2018 (see chart above).

More investments to come

We’ve seen MRFs with strong business models thrive even in the leanest of times by taking a long-term, holistic view of the market in which they operate and addressing each different piece of the process that affects their profitability. At Closed Loop Fund, we’re committed to investing in best-in-class MRF models that can serve as replicable examples.

As investors, we see opportunities for the MRFs of the future to be successful sources of profit and value creation by returning products and packaging to supply chains and enabling municipalities to avoid the financial and environmental costs of landfilling and incinerating. By putting more capital to work in MRFs through our investments, we expect to see a different future for the recycling system, wherein:

- Contracts incentivize low contamination and provide transparency on individual commodity value, enabling public and private customers to optimize their internal systems for maximum value creation.

- Advanced sorting technologies at MRFs produce high-quality bales demanded by the market.

- Strong relationships with end market customers ensure MRFs have options for their material, and the market provides enough premium incentive for quality to justify the investments needed to meet that quality.

The entire system – from municipalities and haulers to processors and manufacturers – benefits when MRFs focus on these future-proof practices.

Ellen Martin is vice president of impact and strategic initiatives for Closed Loop Partners, a group that includes Closed Loop Fund.

Closed Loop Fund’s goal is to accelerate the development of the circular economy by building a closed loop between consumption and reuse of consumer materials. The group does this by investing in infrastructure and technology at all points along the chain of custody of post-consumer materials, from collection and sortation to processing and manufacturing of cutting-edge products that represent new or expanded markets for recycled materials.