Seattle has steadily grown its program since the 1980s, in large part by regularly interacting with the public.

A data-driven approach to materials recovery has helped the city of Seattle steadily expand its recycling program to target a wider range of streams.

City officials point to data the city collects as a vital part of building support for aggressive diversion goals and initiatives. The collected data has consistently driven the conversation on tackling new material streams.

The importance of facts and figures was highlighted when Seattle passed its first disposal ban in 1989, at which point residential yard waste was prohibited from the landfill stream.

Susan Fife-Ferris, director of solid waste planning and program management at city agency Seattle Public Utilities, credits waste characterization studies and other analysis as important facets in building political will to implement the disposal ban and more policies since then.

“You could go back to the data and say, ‘Look, here’s what it would cost to manage it this way and here’s what it would cost to haul it away,’” Fife-Ferris said.

Circumstances converge

Circumstances converge

Recycling in Seattle was offered by small, local privately owned recycling operations beginning in the 1980s. Residents could self-haul material, including aluminum cans, glass bottles and newspaper, to local recycling depots.

Like many communities in Washington, municipal recycling in the Emerald City was spurred into existence by state legislation passed in the late 1980s. At that time, the city began offering curbside three-bin recycling for cans, glass bottles, and newspaper and mixed paper. Plastic containers were added later on.

At the same time municipal recycling began, many of the city’s landfills were coming to the end of their useful lives and needed to be closed down. Meanwhile, federal laws made it more expensive and more difficult to create and manage landfills.

“All of that was kind of a convergence that led to us saying, ‘Are there ways we could manage our waste other than just sticking it into the ground?’” Fife-Ferris said.

At the county level (Seattle is part of King County), officials were exploring waste-to-energy as an alternative to new landfills, which was “extremely unpopular” within Seattle, Fife-Ferris said. The city decided to withdraw from King County’s system and began its own planning for waste management alternatives.

Seattle conducted a “recycling potential assessment” to identify opportunities for diverting materials out of the waste stream for recycling or waste reduction, and the city has been conducting those assessments ever since. They have led to expansions and evolutions in the scope of materials collected through the program.

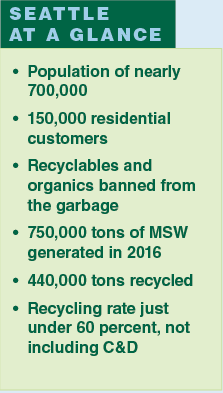

In 2016, the city’s reported diversion rate was 58.8 percent, a number that includes the single-family, multi-family, self-haul and commercial realms.

Program pushes forward

Today, residential collection is contracted through franchise zones to a private hauler, and commercial properties can choose any hauler to collect their recyclable and organic material. The city has nearly 700,000 residents and is in the midst of a boom period, with many of the new residents moving into multi-family housing.

The recycling program went to single-stream collection in the early 2000s and later added food waste and food-soiled paper in the organics receptacle. The city has also mandated material separation, meaning residents are legally required to separate recyclables and compostable materials from garbage.

The city’s recycling program went to single-stream collection in the early 2000s, and curbside organics service has long been available to residents.

Further, beginning in 2017, the city regulated the colors of plastic bags available in grocery stores. Bags that are not compostable cannot be colored green, to avoid confusing customers.

The city also recently began full administration of an ordinance passed several years ago that requires straws, utensils and other foodservice packaging to be recyclable or compostable.

Fife-Ferris pointed to the public popularity of such environmental measures in Seattle.

“We’re very community focused,” Fife-Ferris said of her team’s strategy. “This goes way, way back, decades. Focusing on what people want is what kind of happened in the ‘80s. … People didn’t want a waste-to-energy facility in their backyard.”

But as strong as it is, the community interest isn’t always enough to influence regulatory action. That’s where the information gathered during the regular program analyses comes into play.

“Being able to point to the data and the financial benefit of doing something is very important, because we’re very concerned about affordability and other things too,” she said. “So I think it was a combination of community desire and then cost-benefit analysis. That helps inform the political landscape and provided the political will.”

Seattle continues to engage in the recycling potential assessments every few years to identify new recycling opportunities. But the city is also thinking about recycling in new ways altogether. The goal is to make program decisions that are in line with larger environmental goals such as reduction of greenhouse gas emissions.

“Right now, we really focus on a weight-based recycling program to help define success, as most people do across the country,” Fife-Ferris said. “We’re trying to tee up the conversation about how [we] should define success with respect to materials management. … [Are there] metrics we should be focusing on that involve environmental benefits and involve waste prevention, which a weight-based recycling rate doesn’t?”

This article originally appeared in the December 2017 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

Circumstances converge

Circumstances converge