This story originally appeared in the June 2017 issue of Resource Recycling. Subscribe today for access to all print content.

Anyone involved in materials recovery or general sustainability is by now well aware of the rise of limits on single-use shopping bags.

While plastic bags represent a small component in the waste stream by weight, their durability means they easily turn into a significant source of land-based litter and negatively impact stormwater management systems.

The items also cause headaches at materials recovery facilities, wrapping around equipment. And even when they are put in the garbage stream, problems can ensue: Plastic bags are often the number one litter/flyaway issue at landfills. Such litter and management issues have been heightened as consumers and decision-makers across the world become more cognizant of the marine debris issue.

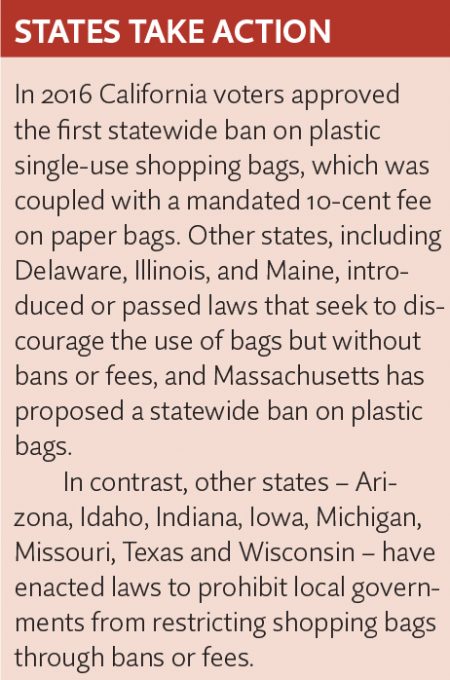

That all explains why local governments have aggressively taken action over the past decade. As of May 2017, nationwide, there were 266 local ordinances in 25 states (including Washington, D.C.) restricting use of single-use bags. This number includes the 110 local ordinances enacted in California prior to implementation of the Golden State’s statewide bag ban in late 2016.

Currently, 16.5 percent of the U.S. population lives in a jurisdiction that’s covered either by the California state law or a local bag ordinance. Following California, the top five states based on the number of local ordinances are Massachusetts, Alaska, Washington, New York and Maine.

What specific strategies are local leaders using to mitigate the plastic bag problem? And how does recycling tie in? Those are questions of critical importance for local officials charged with making smart decisions about bag management in today’s era of ordinances.

Details on consumption and recovery

It’s difficult to find precise data on how many bags are used in the U.S. annually. The U.S. International Trade Commission estimated that each American consumed 319.5 single-use shopping plastic bags in 2014. But other research has concluded the annual per capita consumption of single-use paper shopping bags to be about 122.

Grocery stores generally are the single largest provider of single-use shopping bags. A study conducted recently by Maryland’s Montgomery County, for example, found grocery stores accounted for 70 percent of all bags provided to shoppers in the county. Non-food retailers, meanwhile, accounted for 12 percent, retail super centers came in at 8 percent, restaurants were 3 percent, unclassified stores were 7 percent, and wine and liquors stores accounted for less than 1 percent.

Reliable and consistent data on the recycling of these plastic items is also hard to pin down. The U.S. EPA has data on the recycling rate for plastic bags, sacks, and wraps combined – it was 12.3 percent in 2013 – but this count is inaccurate because it relies on predictive modeling and not waste characterization studies. This leads to underestimated generation figures and overestimated recovery rates.

Using waste characterization studies, Illinois calculated its plastic bag recycling rate to be 1.5 percent in 2009. And California’s recycling rate of plastic shopping bags in 2009 was 3 percent.

The low recycling rate for plastic bags can be attributed to many factors. For plastic bags collected as commingled recycling at the curbs or at municipal transfer facilities, bags must be separated. Given the material’s low market value, there is a quick point of diminishing return where the cost of segregating bags far exceeds potential revenues.

Bags also tend not to be added to curbside systems because of the havoc they bring to recovery facilities. They are a liability because they often get snagged or trapped in automated sorting equipment, causing slowdowns or breakdowns that necessitate daily removal, often by hand. When MRFs are able to separate the material, a common practice is to include bags with commingled plastics (Nos. 3-7). This is the lowest grade plastic, and in certain market conditions, processors or municipalities end up having to pay to move that material.

The plastics industry is currently pushing to develop more of a robust system of collecting bags through drop-off sites at grocery stores and other retailers. To that end, the American Chemistry Council (ACC) has worked to push forward its Wrap Recycling Action Program (WRAP), which has helped to develop infrastructure and awareness around plastic film recycling as a whole. However, according to the ACC’s most recent report on plastic film recovery, post-consumer plastic bags and wrap collected through retail programs in the U.S. fell to 194 million pounds in 2015, a 12 percent drop from 2014.

The spread of the strategy

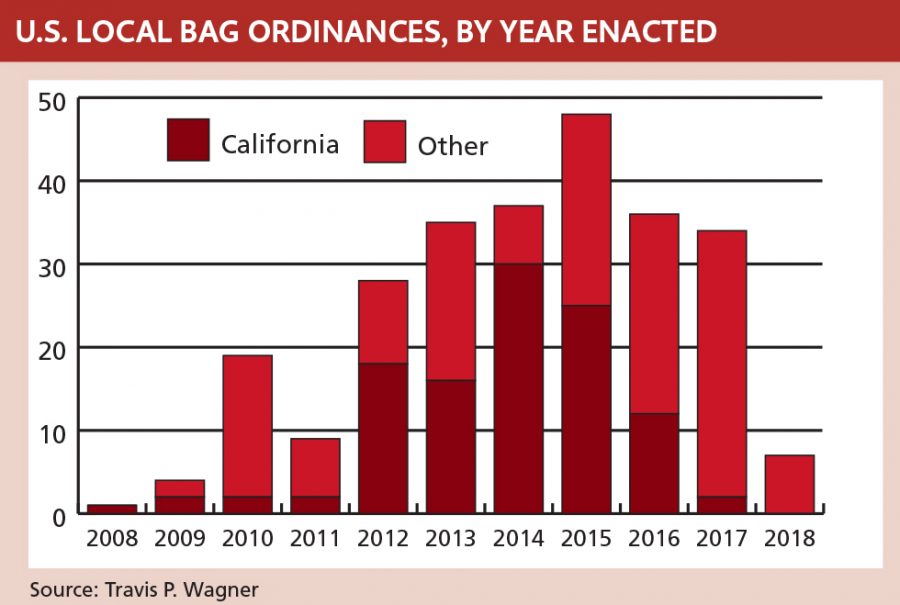

The recycling difficulties associated with plastic bags have helped spur the move to ordinances at the local government level. The chart on this page offers a portrait of municipal bag policy implementation in recent years.

While the first plastic bag ban was adopted by Nantucket, Mass. in 1990, it was not until after San Francisco’s plastic bag ban in 2007 that the number of local ordinances increased dramatically. It also is interesting to note that San Francisco originally proposed a fee on plastic bags, but the state legislature passed a law in 2006 prohibiting local fees on plastic bags. In response, San Francisco passed a ban on plastic bags and a fee on paper bags, which were actions not prohibited under the state legislation.

The details on the limits imposed by enacted policy vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. The most common strategy has been a ban on plastic bags coupled with a fee on paper bags. Of the 266 local ordinances, 94 percent ban plastic bags – the others impose a fee on bags without a ban (10 cents is the most common charge). And of the 94 percent that do ban plastic bags, 58 percent include a fee on paper bags.

The ban and fee approach has proven to be very successful in reducing total single-use bag consumption. For example, in Santa Barbara, Calif., following the imposition of a 10-cent fee on single-use paper bags and a ban on plastic bags, total consumption of bags decreased by 89.3 percent, according to a 2016 Santa Barbara City Council report.

Fees in themselves can be effective as well. Ireland’s bag tax adopted in 2002 resulted in a 90 percent reduction in per capita plastic bag consumption (from 328 to 21 bags per year). Researchers have also found that when faced with a per-bag fee, shoppers increasingly skip bags for small purchases, pack more goods into each bag or bring their own bags. One of the challenges with bag fees is the rise in self-checkout kiosks that rely on customer honesty to pay the bag fees.

We can look again at Maryland’s Montgomery County for a unique example of charging for bags. There, all bags are subject to a 5-cent tax, which must appear on the receipt. Retailers are required to remit these revenues to the county, and the money is used on water quality projects.

In other instances, local governments have sought to reduce the environmental impact by requiring bags, especially those made of paper, to contain post-consumer material or sustainably grown fiber. To encourage reuse, ordinances initially defined reusable plastic bags as those thicker than 2.25 to 3 mils (1 mil is one-thousandth of an inch, and a typical plastic bag is 0.5 mil). For instance, in Washington, D.C. plastic bags must be recyclable, and paper bags must contain 40 percent post-consumer recycled content. Bags also must be imprinted with a phrase such as “Please Recycle This Bag.”

However, some retailers in different areas responded to such requirements by simply giving away thicker “reusable” plastic bags, thereby skirting the intent of the ban. This problem was particularly prevalent in Hawaii, where all counties have instituted plastic bags bans.

As a result, newer ordinances increasingly are using 4 mils as the minimum thickness for defining reusable plastic bags or prohibiting the free distribution of reusable bags. In addition, ordinances increasingly have defined reusable bags based on durability requirements (for example, minimum life span and ability to carry a specified minimum load) and design requirements such as cotton, fiber, or other machine washable materials. These efforts all aim to discourage thicker plastic bags.

Finally, it’s important to note that single-product bans can have unintended consequences. A previous statewide law in Maine that went into effect at the start of 1990 restricted the use of plastic bags with no restriction on paper bags led to a significant increase in the consumption of single-use paper bags. Carbon footprint concerns and reports of higher costs to retailers for paper bags caused a quick repeal of the Maine law.

The education component

As often quoted in recycling programs, education is essential but insufficient. Programs have generally not seen success by relying solely on initiatives such as “bring your bag” campaigns.

One notable effort to bring residents on board with bag goals has been implemented in Eau Claire, Wisc. It has rolled out a plastic bag “education phase” to try to encourage local shoppers to reduce plastic bag use by turning to reusable bags. If in two years, usage is not cut by 45 percent, an “incentive phase” will begin, during which retailers would offer a 5-cent credit to those shoppers who bring their own bags. If a year employing that strategy still does not lead to sufficient reduction, then a “requirement phase” starts – this would involve rolling out a 10-cent fee on single-use paper and plastic bags.

Researchers have also identified some interesting psychological elements that might be hindering efforts to cut down on single-use bag consumption. A 2016 study published in the Journal of Consumer Research found that men are less likely to engage in environmental actions viewed as feminine – in the study, bringing reusable bags was included in the “feminine” category. This type of research suggests that simply providing information does not necessarily mean a change in behavior. However, when coupled with bans or fees, education has been highly influential.

Researchers have also identified some interesting psychological elements that might be hindering efforts to cut down on single-use bag consumption. A 2016 study published in the Journal of Consumer Research found that men are less likely to engage in environmental actions viewed as feminine – in the study, bringing reusable bags was included in the “feminine” category. This type of research suggests that simply providing information does not necessarily mean a change in behavior. However, when coupled with bans or fees, education has been highly influential.

Mandating that retailers take back plastic shopping bags is another approach. California, Delaware, the District of Columbia, Maine, New York and Rhode Island have all have enacted laws to require retailers to provide free in-store collection of plastics bags. However, it’s worth noting that providing an opportunity for recycling does little to affect consumption at checkout. In fact, offering recycling at the generation point has been shown to actually increase consumption through the “moral licensing” effect – the idea here is that individuals feel better about consuming more if recycling opportunities exist.

As leaders continue to move forward on sustainability efforts, municipalities continue to forge ahead with a variety of local-based approaches seeking the elimination or reduction of single-use shopping bags. And bags may be a gateway to additional action.

Because of their success with bags, local governments have been expanding their focus to eliminate or reduce other problematic single-use consumer products including expanded polystyrene (EPS) food-service items and packaging, plastic straws and lids, plastic utensils, and the retail sale of drinking water in plastic bottles.

Travis P. Wagner is a professor of environmental science and policy at the University of Southern Maine. His research focus is on solid waste management practices and policies and extended producer responsibility. He can be contacted at [email protected].