This story originally appeared in the February 2017 issue of Resource Recycling.

Subscribe today for access to all print content.

More than a decade after U.S. states started passing laws putting electronics manufacturers on the hook for the collection and recycling of their products, some are finding their programs are in need of tweaks.

To address the issue, stakeholders have begun developing updated legislation, but 2016 could have been described as a year of statehouse stalemates: Very few bills aimed at e-scrap improvement actually passed into law.

New Jersey, which served as a prime example of the industry push and pull complicating the process of making changes to an already existing state program, was one notable exception.

The state saw the veto of an initial e-scrap reform bill, calls for recyclers to aggressively lobby legislators (even inside a Capitol parking garage), lawmakers overwhelmingly voting to send the governor the same bill he previously rejected and, finally, a signature from the governor.

What allowed the legislative update to happen? And what can the larger industry learn from the high political drama and e-scrap infrastructure issues that have been seen in the Garden State?

Costs cause collection site closures

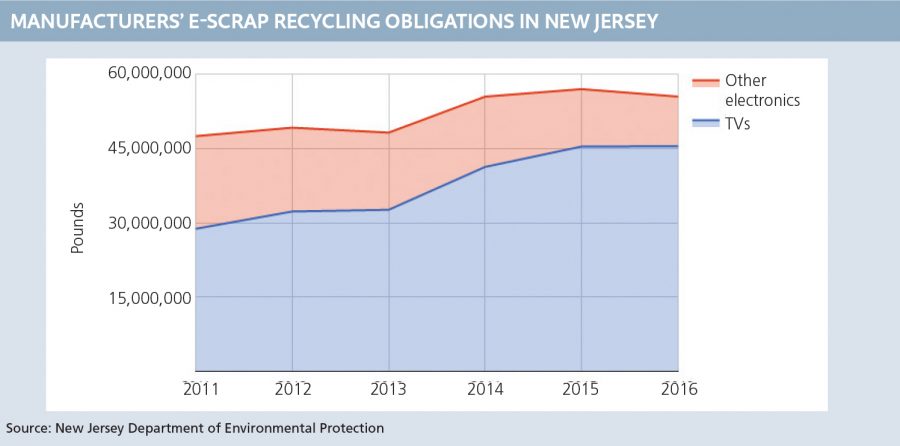

New Jersey first made original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) responsible for collecting and recycling electronics in 2011, the same year a disposal ban went into effect. Under the law, recycling of covered items is supposed to be provided free of charge for consumers and small businesses.

But in recent years, complaints of reduced collections, costs to local governments and illegal dumping were heard in New Jersey.

According to data supplied to Resource Recycling by the Association of New Jersey Recyclers (ANJR), in New Jersey’s Burlington County, 12 out of 20 municipal programs have closed due to cost difficulties.

Meanwhile, in Middlesex County just three out of 25 towns have a collection program and all three are covering some of the costs. And in Sussex County, all five previous municipal programs have ceased operations.

ANJR leaders blame equipment manufacturers for what the association says is an eroding state program.

“I’d say the biggest problem is the shifting of costs from the manufacturers to the municipalities,” Marie Kruzan, the ANJR executive director, said in an interview.

OEMs have drastically reduced payments to recycling companies that have contracts to pick up and process scrap collected by local governments, Kruzan noted. That has forced the e-scrap companies to cut service to some areas or shift costs to municipalities, a fact that has accounted for some areas ending collection.

“The number of canceled programs is expected to grow as local and county governments, still covered by older, multi-year contracts, find that they are unable to renew those agreements with e-waste recycling companies without incurring new costs that must be borne by their taxpayers,” Kruzan and lobbyist Frank J. Brill wrote in an op-ed for Resource Recycling sister publication E-Scrap News last fall.

In terms of collections, OEMs are focusing on high-volume sites in heavily populated areas, where they can reach their targets in a more cost-effective manner. That leaves rural and more far-flung southern New Jersey communities out to dry, unless they want to pay for the service, Kruzan said.

OEMs are reporting that they’re reaching their targets midway through the year, after which they close their programs until the next year. Meanwhile, the public continues to drop off electronics. This is a scenario that has played out in a number of state e-scrap programs across the country.

The role of larger market forces

Walter Alcorn is vice president of environmental affairs and industry sustainability at the Consumer Technology Association, which represents many OEMs. In his own op-ed for E-Scrap News, he noted that over the past decade, manufacturers have gotten smacked whenever issues arise in a state program.

However, Alcorn stated, the issue is not one driven by OEMs’ strategy or contracting – instead, it boils down to the effects of depressed markets and profits.

“Former collector practices – expensive collection events, collection of electronics not covered under the state law, turning a blind eye toward scavenging valuable components in otherwise negative-value e-scrap – became unaffordable,” he explained. “Suddenly, local governments and recyclers felt the effects of national market forces pushing them to reduce costs and increase efficiencies.”

Alcorn said smacking OEMs with a bigger stick won’t work in New Jersey for a few reasons. Manufacturers are already meeting the state’s high recycling targets each year. Local recycling companies are struggling to find a role in a new recycling system where economies of scale are king. And markets for new electronics are stressed, with TV sales flat and monitor sales declining.

Jason Linnell, executive director of the National Center for Electronics Recycling (NCER), pointed to various other rubs that were causing consternation in New Jersey. While OEMs might want to contract with a national or regional e-scrap recycling company to boost efficiencies, local governments often want to partner with the same local vendors they’ve always used.

Additionally, New Jersey’s program had called for convenient collection opportunities around the state but doesn’t put the requirement on any one OEM or group of OEMs, Linnell said. That put regulators in a pinch when various compliant plans are submitted but, taken together, they still leave gaps in service statewide. Add to that a mismatch between targets and collected volumes, which aggravates the situation.

A battle over legislation

Enter Senate Bill 981, introduced to the New Jersey legislature in early 2016.

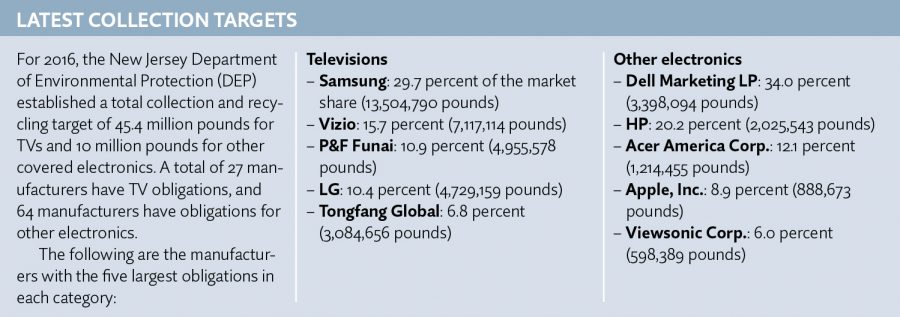

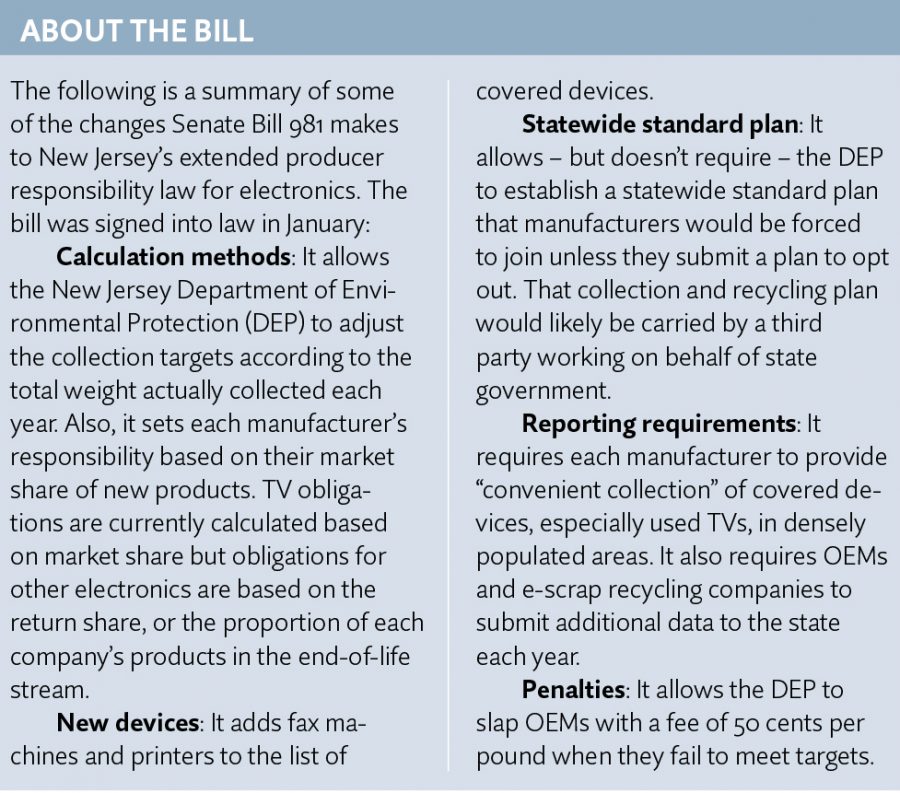

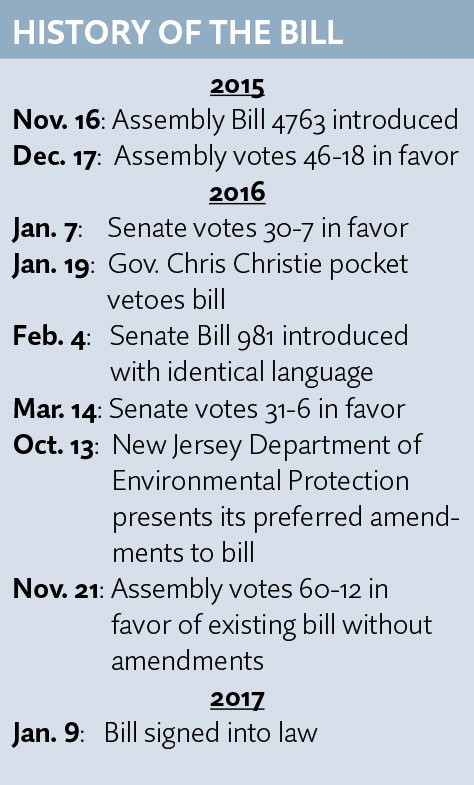

The bill makes several significant changes to the state program (see sidebars for bill details and history). It changes the way weight targets are calculated, adds fax machines and printers to the list of covered materials, requires OEMs and e-scrap companies to report additional data to the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), and allows the state to impose fees on manufacturers that fall short of their targets.

Notably, and controversially, the legislation also allows – but doesn’t require – the DEP to establish a statewide standard plan that manufacturers would be forced to join unless they submit a plan to opt out. That collection and recycling plan would likely be carried out by a third party working on behalf of state government. It’s an approach employed by Oregon and Vermont, where NCER serves as a contracted third-party administrator.

Kruzan said the statewide standard plan could be used by the state to plug gaps in service left by the OEM-managed plans.

Early in 2016, Gov. Chris Christie, a Republican, vetoed a bill that had identical language as S-981. In response, the bill’s primary sponsors, Democrats Sen. Bob Smith and Rep. John McKeon, re-introduced the legislation as S-981 during the next session.

OEMs opposed the bill. After its March 14 approval in the state Senate, S-981 stalled for much of 2016 because the DEP asked the state Assembly to delay the vote while it conducted stakeholder meetings, aimed at sussing out possible compromise amendments.

After the meetings were held, the DEP came out and suggested amendments that would shift greater control away from state government and toward manufacturers, some of which are headquartered in the Garden State. Among other things, the amendments would have nixed the possibility of adding a third-party-administered statewide standard plan.

Recycling industry representatives objected loudly and called for lawmakers to reject the amendments. The DEP proposal “was so loaded with concessions to the manufacturers and lacking vital enforcement provisions that it was rejected by all segments of the recycling community,” Kruzan and Brill wrote in their E-Scrap News op-ed.

Recycling industry representatives objected loudly and called for lawmakers to reject the amendments. The DEP proposal “was so loaded with concessions to the manufacturers and lacking vital enforcement provisions that it was rejected by all segments of the recycling community,” Kruzan and Brill wrote in their E-Scrap News op-ed.

Kruzan sent a Nov. 17 email to recycling industry members urging them to get in touch with lawmakers in advance of a Nov. 21 vote in the Assembly, the last approval needed to send the bill to Christie. She also suggested they head to the Capitol building in Trenton the morning of the vote “to waylay assemblymembers on their way from the parking garage to their respective caucus meetings and ask for a yes vote.” In an interview, Kruzan said bill supporters did in fact engage lawmakers after they parked their cars.

Additionally, local governments that are being forced to spend money to keep their e-scrap recycling approved resolutions, provided by ANJR, in support of the bill.

In the end, lawmakers sent Christie the same language he previously vetoed. He signed the bill on Jan. 9.

Brings up new questions

Christie’s office did not release a statement on his signing of S-981. When asked why Christie signed a bill with language that was identical to one he vetoed, spokesman Brian Murray referred to a general statement the office issued in January last year: “Having the legislature pass more than 100 bills in such a hasty and scrambled way, praying for them to be rubber stamped, is never a good formula for effectively doing public business.”

Christie, who leaves office in one year, has never had a veto overridden, which is said to be a point of pride for him. S-981 passed out of the legislature by wide margins (31-6 in the Senate and 60-12 in the Assembly).

“Your support, your calls, your resolutions made this possible,” Kruzan wrote in an email to bill supporters. “All that work made it clear to the governor that there was enough support for this bill to override his possible veto.”

The passing of the legislation into law now brings up new questions, including when specific provisions can be implemented. The bill says it goes into effect immediately, but it’s unclear how that will work on the ground.

“It’s not a panacea. It’s not going to immediately solve every problem,” Kruzan said. “I think people need to accept that. It’s a step in the process, and we still have a lot of unanswered questions.”

For example, the NJDEP is currently reviewing OEMs’ 2017 collection and recycling plans. It has not yet released 2017 collection and recycling targets. And some parties are saying new provisions don’t go into effect until 2018, Kruzan said.

Kruzan noted that passage of a bill doesn’t bring guarantees on implementation.

“There’s lot of ways to kill this,” she said. “If you don’t give [NJDEP] enough staff to do the work, how’s it ever going to get done?”

Meanwhile, other states that were unable to usher their e-scrap reform bills to the finish line are left looking to the future to solve program growing pains.

In Wisconsin, for example, a significant revamp was proposed in the legislature this year but failed to advance out of committee. The same thing happened in Pennsylvania.

“The legislative proposals have not been consensus type of proposals,” Linnell said, “except for the case of Minnesota.”

Lawmakers in the North Star State unanimously passed a bill this year substantially reconfiguring their program. The legislation, which was signed into law by Gov. Mark Dayton, reclassified certain devices and placed collection targets for upcoming years in state statute.

Additionally, the law requires manufacturers to work with e-scrap recycling companies holding third-party certifications, gives them recycling credits when they exceed targets and allows regulators to waive fees charged when companies fall short of targets.

Linnell predicted “the path forward out of the situation will be messy.” He expects some states to tinker with their programs and find compromises providing incremental progress. But that could mean some retraction of programs, rather than expansion, he noted.

Still, talks behind the scenes could translate to the passage of bills in legislatures next year, Linnell said.

“There are a lot of discussions and negotiations and things like that going on behind the scenes,” Linnell said. “We may see more in 2017 than we saw in 2016.”

Jared Paben is the associate editor of Resource Recycling and can be contacted at [email protected].